Tony Clayton was 30 years old, and just two years out from passing the Louisiana bar, when he walked into court in February of 1994, prepared to try his first murder case. He was, in his words, a “braggadocious kind of little young jit,” determined to prove himself with a case that would test even the most veteran of prosecutors.

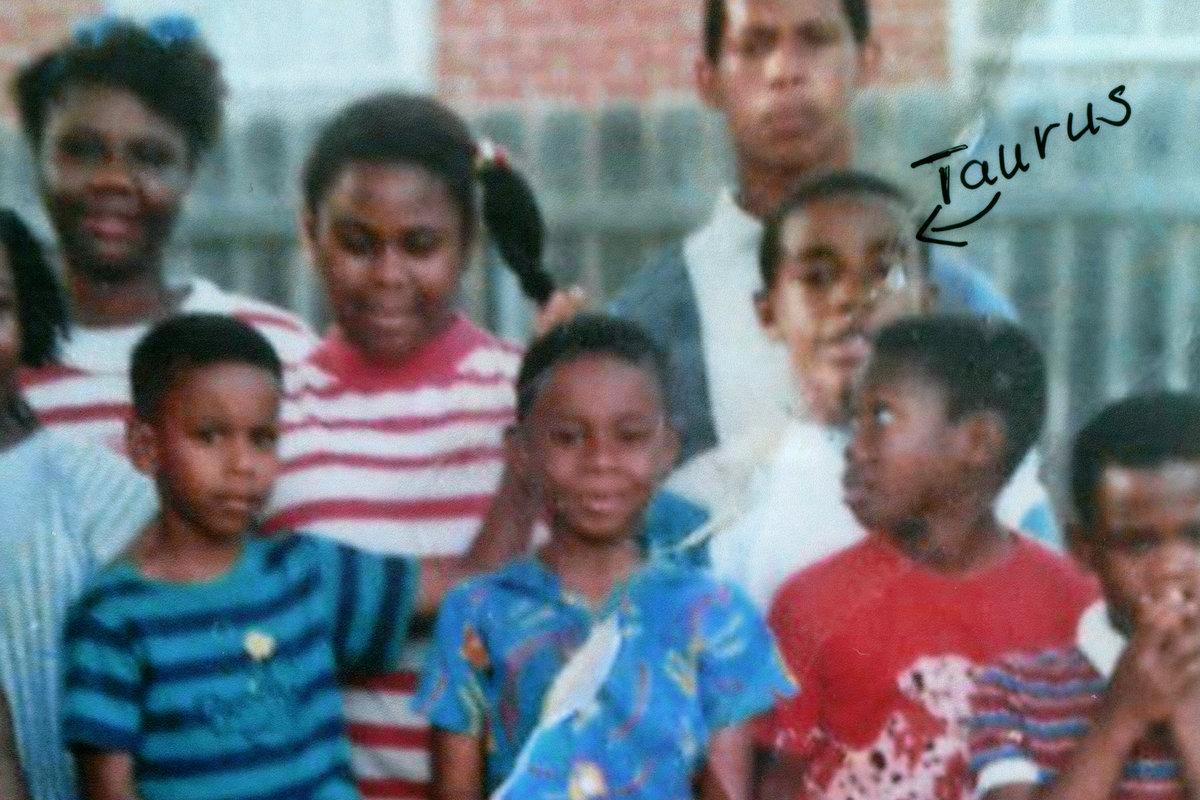

The defendant, Taurus Buchanan, stood charged with second-degree murder—accused of throwing, at the age of 16, a single, deadly punch in a street fight among kids. If convicted, an automatic sentence would fate him to spend the rest of his life in prison, with no hope for parole. A section chief in the East Baton Rouge District Attorney’s Office had told Clayton that securing a murder conviction under these circumstances would be a tough task. But Clayton had told her, “Ah, man, I can convict. I can do it. Just give me the damn case.”

Clayton, who is African American, says he had been hired by the district attorney’s office in part because of his ability to connect with black jurors. He became so good in the courtroom he could inspire profane awe. “If Tony Clayton told jurors to eat shit out of his hand, they would do it,” one court clerk told us. To Clayton, a prosecutor was akin to a projectionist in an old movie theater. “That guy where the light’s coming from, he’s projecting an image on the screen. And that’s me. I’m projecting to those jurors how I want them to view my case.”

On the opening day of the trial, Clayton told the jury pool that young as Taurus was, a murder conviction would send him away, never again to be free. “Does that bother you at all to determine the fate of this young man?” Clayton asked a 19-year-old woman. “No, it doesn’t,” she said. “What about you?” Clayton asked another woman. “No, it wouldn’t,” she said.

Taurus Buchanan stood trial in the era of the “superpredator,” the label applied to violent juveniles in the mid-1990s, when states and the federal government passed one tough-on-crime law after another. Today, two decades later, a trio of rulings from the US Supreme Court has peeled back some of those laws, recognizing the folly of assigning equal culpability to adults and kids. In October, the court heard arguments in a fourth case, and how that ruling comes down could determine what happens to hundreds of lifers sent to prison when they were kids.

On a Thursday morning in July of 1993, Taurus Buchanan was getting ready for an evening flight. He ironed, folded, and packed his dress clothes, including a pair of olive-green pants and a green and black button-down shirt. Taurus and his father, Elton Mitchell, were heading out for a summer tour.

Mitchell played electronic keyboard with Willie Neal Johnson and the New Keynotes, a gospel band with upcoming concert dates in New York and the Midwest. Johnson had agreed to let Taurus tag along, and some of the more experienced musicians were going to help Taurus develop his drumming skills.

It was Taurus’ mother, Everlena Buchanan Lee, who’d bought him a drum set when he was little, and he kept the beat for the choir at Community Bible Baptist Church. (“I wasn’t that good,” he laughs now. “But nobody said it, because it was about God. It wasn’t about whether I was good or not. It was about making a joyful noise unto the Lord.”)

Buchanan Lee dated Mitchell in middle school and high school, and Taurus was born when she was 15. She’d eventually marry another man, and Taurus would live at his grandmother’s house on East Baton Rouge’s Kaufman Street. By the time Taurus was in middle school, Buchanan Lee says, her life had fallen into “Do my work, come back home, get a beating, get high, go to work, come back home.” When Taurus was 14, she was charged in connection with an armed robbery after her husband held up a Circle K. Buchanan Lee pleaded guilty to accessory after the fact, and ended up with a suspended sentence and probation. Then she got divorced, and got clean. Taurus insisted she get a house close to him, on his street.

The night before Taurus’ trip, Buchanan Lee had wanted him to sleep at his father’s, but Taurus refused. Because of his mother’s past, and the rough neighborhood, Taurus, a muscular 150 pounds, had cast himself as the family protector, quick to use his fists. “If you stood in front of his mom’s house or his grandmother’s house and sold drugs, you had a fight on your hands,” Buchanan Lee says.

“We always had fights,” Taurus explains now. “Whatever school I went to, you was gonna fight…They were gonna push you, they were gonna bump you.” It could be you were different, he says, or not from the area, or were talking to a girl someone else wanted to talk to. Fighting had its own language—crowding, wilding, getting into the mix—and its own rituals. “Before every fight,” he says, “people would tie up their shoelaces and tighten their sneakers.”

When some kids from a rival neighborhood started getting guns, Taurus figured he’d better do the same, so he paid a junkie $10 for a gun with no firing pin. When Taurus got caught with it, the school contacted police, who released him to his family. He says a juvenile judge gave him probation. He now says that if he had spent some time locked up for any of it, even a night, “that would have gotten my mind right.”

As Taurus packed, his cousins Mario Hutton and Colin Knox were in his living room watching television. Mario was 12, Colin, 15; the three were inseparable. “You saw me, you saw them,” Taurus says. After a while, Mario and Colin wandered out and headed up the street. Soon enough, Taurus followed.

That same morning, about a mile away, on the other side of Scenic Highway, Jacques Brown finished a bowl of Frosted Flakes, then told his mom he was heading out to pick up work cutting a lawn. Jacques was one of eight kids in a family that didn’t have much except “a lot of love,” says his mother, Janice Brown. He hopped on a bicycle with a friend.

Jacques was 12 but, according to his aunt Joann Phillips, “looked like he was just 9 or 10. Jacques was skinny, skinny, skinny, nothing but bones.” He was a good kid, she said. The Sunday before, when his family couldn’t take him to church, he knocked on neighbors’ doors until he found a ride.

The two friends crossed the highway, a north-south thoroughfare that to some in Baton Rouge served as a neighborhood boundary. As morning turned to afternoon, they made their way along Kaufman Street. That’s when Colin Knox saw Jacques—and began tying up his shoelaces.

That year, Jacques and Colin had been in the fifth grade at the same elementary school, but had different teachers. The local kids often fought over turf: whose teacher was better, what side of the highway you belonged on. On the last day of school, Jacques and Colin got into it.

Now, on Kaufman Street, the insults moved from the stuff of playgrounds—“You look like a frog”—to more dangerous ground. “He called me a punk pussy-assed nigger, then I got mad and I called him a punk pussy-assed nigger back,” Colin would later tell police.

Colin threw the first punch, and didn’t let up. Mario joined in, neighbors looking on. Then Taurus waded in and landed one blow. Jacques crumpled, and never got up.

Accounts would vary on whether other kids in the neighborhood then piled on, beating Jacques while down. But it soon became clear how badly he was hurt. “I poured water on Jacques’ face, on his forehead, trying to wake him up,” Taurus says. “I was like, ‘Wake up, Jacques,’” but the boy’s eyes rolled back. He saw some blood in Jacques’ mouth, heard gurgling noises, and saw his body stiffen.

An ambulance took Jacques to the hospital; the cops picked up Taurus, Mario, and Colin. In the police car, Mario began to cry and Taurus wiped his tears. At the station, a policeman handcuffed Taurus to a bar on the wall. When officers unchained him to photograph the knuckles of his right hand, Taurus was shaking so forcefully that an officer had to hold his hand still. He was in an interview room with his mother when a detective walked in with news: Jacques Brown was dead.

Taurus and his cousins were booked and taken to juvenile detention, where they were sprayed for lice and given green prison uniforms. Mario told Taurus he was scared. “Man, I’m scared too,” Taurus responded.

In 1994, the year Taurus Buchanan stood trial, a Chicago gang member named Robert “Yummy” Sandifer—11 years old, 4-foot-6, with a stunningly long criminal record—became a suspect in the shooting death of another child, 14-year-old Shavon Dean. As police searched for Robert, two other gang members—brothers, ages 16 and 14—took the 11-year-old to an underpass and murdered him.

Robert’s story made the cover of Time, and other stories of youth violence mounted. Beyond the anecdotes, some researchers dug into numbers—looking at demographics and spiking crime rates—and claimed that the worst was yet to come.

In January 1996, a Newsweek headline summed up the nation’s fears: “Superpredators Arrive: Should We Cage the New Breed of Vicious Kids?” At the forefront of the lock-’em-up movement was John DiIulio Jr., then a political scientist at Princeton. He foresaw a “ticking crime bomb” of tens of thousands of violent young thugs “on the horizon,” “morally impoverished” kids for whom murder and rape came naturally.

“Let the government Leviathan lock them up and, when prudence dictates, throw away the key,” wrote DiIulio in an academic journal; he saw little chance for youths to be rehabilitated “once they have crossed the prison gates.”

Legislators heeded the call. Between 1992 and 1999, 49 states and the District of Columbia made it easier to try juveniles as adults. Some states removed consideration of youth altogether, replacing discretion with compulsory triggers. By 2012, there were 28 states across the nation that were handing out mandatory life-without-parole sentences to juveniles.

One was Louisiana, where Taurus exemplified how mandatory sentencing could render a defendant’s youth meaningless. Once he was charged with second-degree murder, Taurus was automatically tried as an adult because he was over the age of 14. If convicted, he would automatically be sentenced to life without parole.

By 2015, more than 2,230 people in the United States were serving life without parole for crimes committed as juveniles, according to data1 compiled by the Phillips Black Project, a nonprofit law practice that collected information on all 50 states. In 2007, the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit law organization based in Alabama, found that there were 73 cases in which kids were sent away for crimes they committed at age 13 or 14. One was sentenced to life for kidnapping, another for sexual battery, another for taking part in a robbery in which someone was shot but survived.

The Phillips Black data shows that, with 376, Pennsylvania currently has the most people serving juvenile life sentences. But Louisiana has a higher number of such inmates per capita than any other state. Of the 247 inmates in Louisiana, 199 are African American. In East Baton Rouge Parish, where Taurus stood trial, the racial disparity is even starker: Almost half of the parish population is white, but 32 of the 33 serving juvenile life-without-parole sentences are black.

| Rank | County | Number |

|---|---|---|

Ask lawyers why they chose the law, and the answer often includes talk of justice, principle, or righting wrongs. Tony Clayton’s reasons were more pragmatic. In a book he co-authored about another case, he explained his choice:

There is no altruistic reason why Tony decided to become a lawyer. He did it simply to impress a girl and, in the process, found his true calling. “Paula was in undergraduate school, and she liked a guy who was in law school,” he explained. “This guy was nice looking and had a car. He was pushing me out. I knew if I wanted to get her, I had to go to law school.”

Paula, whom Clayton married, later became a family law hearing officer, and the two shared views on juvenile crime that were in lockstep with the country’s. Clayton told us about a personal incident: “The alarm had gone off in our house. And I had the gun and I was walking in looking. She tells me before I go in, ‘If he’s a kid, shoot him. If he’s an adult, reason with him.’” What she meant, he explained, was “not that she’s a cold-blooded vicious lady. She knows, just as I know, that a 15-year-old, 16-year-old, if I caught him in my house and he had a gun, he doesn’t have a clue how to try to negotiate his way out of the house. He believes in leaving no witnesses. And he has no sense of what his consequences are.”

When Clayton had been hired, he says, he told the district attorney that black jurors detest crime as much as anyone else. “You need to have black prosecutors who can relate to them—but they will convict quickly.”

But when he set out to impanel a jury for Taurus’ trial, Clayton most wanted conservative jurors, people angry and fearful about crime, people he suspected would appreciate tough measures to stamp it out. Allowed to remove people from the jury pool, he used seven of eight strikes on African Americans, leaving the box filled with 10 whites and two blacks.

The panel comprised seven men and five women, ranging in age from 20 to 77. They included a welder, forklift driver, painter, a university student, a manager at General Motors, a veteran of World War II. During jury selection, the man who became jury foreman said he believed there was heightened violence in East Baton Rouge Parish, which he linked to drugs and “more liberal thinking by individuals.”

Clayton’s star witness was Mary Rodgers, who lived on Kaufman Street and had seen Jacques Brown being beaten. Before Taurus entered the fray, she testified, the two other boys “kept on hitting him, they kept on hitting him, they kept on hitting him,” while Jacques pleaded, “Leave me alone, leave me alone.” When Taurus showed up, Rodgers testified, “He say, ‘I’ll show you, this is how you do the bitch.’ Pow, he hit him in the left temple.” She even acted the scene out by lying down on the courtroom floor.

“Was Taurus bigger than the other guys?” Clayton asked.

“Yes, sir, and definite,” Rodgers said. “Hit him blind side,” she said of Taurus’ blow.

Clayton’s next witness was Mario Hutton. What happened to Jacques after Taurus threw that punch? Clayton asked. “He remind me of the Wizard of Oz, when the witch was melting,” the 12-year-old said.

Clayton’s final witness was a pathologist who described the blow Jacques received: “You don’t see the punch coming in and the muscles don’t have a chance to keep that head in place. And instead there is a hyperextension of that neck, and then that small artery coiling up and coming from below, upward into the brainstem, just lacerates—breaks and then bursts into bleeding.” Had Jacques seen the punch coming, the pathologist testified, “we wouldn’t be here.”

The defense’s case was short. Although Taurus didn’t testify, his attorney, Ron Johnson, emphasized all the blows that were landed by others. Wanting the jurors to feel how long it was before Taurus got into the fight, Johnson stood in court and watched the clock, waiting for two, then three minutes to pass.

In his closing argument, Clayton called Taurus a “cold-blooded murderer” and “Taurus the bull.”

“Do you think this is a little boy?” Clayton asked the jury. “This is a man.”

Johnson objected, saying, “Under Louisiana law, he’s not an adult,” but the judge overruled the objection.

“There’s 150 pounds of all man that killed that little child, that killed that little kid, that killed that baby,” Clayton told the jury.

While Taurus faced a life sentence, Colin Knox pleaded to manslaughter and was sentenced to seven and a half years. Mario Hutton’s case remained in juvenile court, and he was put on probation.

The jury voted 10 to 2 to convict Taurus of second-degree murder—and in Louisiana, 10 votes were enough. The two who voted to acquit, both white, were among the oldest—one 73, the other 58. Taurus received a mandatory sentence of life without parole. He was one of at least 19 juveniles to receive that sentence in Louisiana in 1994 alone.

After he was sentenced, Taurus was held at the East Baton Rouge Parish Prison. There he had hot water, soup, urine, and feces thrown on him by hardened inmates. In May, three months later, he was transferred to the Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola—America’s largest maximum--security prison, an 18,000-acre outpost that is home to 6,280 inmates in a curl of the Mississippi River.

On the bus ride to Angola, a few returning inmates had warned him to watch for predators who might try to fight or rape him. So when Taurus walked to his cellblock in feet and arm shackles, his eyes picked up every movement around him. When he took his cell’s top bunk, he says he was thinking, “Please don’t let me get killed, or have to kill nobody.”

His first work assignments alternated between cutting grass with a hand-held blade and picking purple hull peas, okra, eggplants, and squash—all in the sweltering heat, under the watch of armed guards on horses. The labor raised painful blisters on his hands and feet. He eventually learned to urinate on the irritated skin at night for comfort.

When his mother and grandmother came to visit, he had what he calls a coming-clean moment. He talked about all his fighting; he told them he had even sold drugs. He told them: “I didn’t turn out the way you probably expected me to turn out. I’m sorry, I wish I could do it better and do it over.” He added, “I made a choice and I gotta live with it.” They held his hand, and hugged him. His grandmother told him, “Start living your life better right now.”

Taurus turned to his faith: “The word of God says I shall live and not die.” He read the Bible. He read magazines, be it National Geographic or People. He read his hometown newspaper. And he wrote letters to his family.

By age 20, he earned his GED and learned to cook. He later became certified in carpentry, and joined a program to deter juvenile crime, giving talks to middle and high schoolers and to Bible study groups and Boy Scout troops. His stack of certificates, more than 40 deep, includes two for anger management. By the time he was 29, Taurus earned Class A Trusty status, the highest classification at Angola. With it came certain privileges, like greeting outside guests. In 2010, he married a woman named Deborah whom he met when she came to visit two childhood friends. She saw Taurus working at the concessions counter, and noticed he was shy, with a nice smile.

From 1994—the year Buchanan was sentenced—to 2013, the number of homicides committed by juveniles nationwide fell by about 75 percent. Experts still debate why, but the prophesied horde of young, remorseless killers never emerged. In a 2001 interview with the New York Times, DiIulio described an epiphany he had during a Palm Sunday Mass: Instead of discarding troubled kids, we should wrap our arms around them. (DiIulio had also just become the first director of the White House Office of Faith Based and Community Initiatives, under President George W. Bush.) He came to embrace church programs, not prisons, as an aid for wayward teens.

During those same decades, neuroscientists had been researching the development of the adolescent brain, and numerous studies soon confirmed what most parents already knew: Compared to adults, the average teenager is more impulsive, volatile, and vulnerable to peer pressure—and less aware of long-term consequences. This research also showed that the adolescent brain is plastic—it can, and does, change.

Eleven years after Buchanan was sentenced, the Supreme Court, citing the “evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society,” issued the first in a string of landmark decisions that recognized that juveniles were less responsible for their actions than adults.

In a 2005 ruling, the court banned use of the death penalty for crimes committed by juveniles. Writing for the majority, Justice Anthony Kennedy noted the link between adolescence and reckless behavior: “From a moral standpoint it would be misguided to equate the failings of a minor with those of an adult, for a greater possibility exists that a minor’s character deficiencies will be reformed.”

Five years later, the Supreme Court prohibited sentencing kids to life without parole for cases that didn’t involve a homicide. And in 2012, in Miller v. Alabama, the court extended that ban to mandatory life-without-parole sentences for homicides. One of the petitioners, Evan Miller, was 14 years old when he and a friend killed a neighbor by beating him with a baseball bat and setting his trailer on fire. Growing up with an alcoholic mother and abusive stepfather, Miller had tried four times to kill himself, the first attempt coming when he was only six.

By the time of the Miller ruling, Buchanan had spent 18 years, 11 months, and 10 days behind bars. But not all states treated the ruling as retroactive. In Louisiana, the state Supreme Court refused to apply Miller to those sentenced in years past, saying the ruling, while new, did not constitute a watershed change “essential to fundamental fairness.”

West of Louisiana, across the Sabine River, Texas went the other way, reopening its cases. So, to the east, across the Pearl River, did Mississippi. As Jacques Brown died on the wrong side of a highway, Taurus Buchanan serves life on the wrong side of a river.

On a June evening in 2005, Angola hosted a boxing tournament, with inmates from five prisons squaring off in front of an audience that included nine state lawmakers and three members of the state parole board.

Buchanan, now 28, was there as a server, bringing food and drinks to the special guests. As he went table to table, he recognized one visitor: Tony Clayton.

Buchanan didn’t know what to do. “I didn’t want to cause alarm,” he says. “I said, ‘Well, here goes everything.’ I walked over there and I said, ‘Excuse me, sir, Mr. Clayton, would you like some water or a soda?’” Clayton looked up—and told Buchanan he looked familiar.

“Yes, sir, I’m Taurus Buchanan.” He then repeated, “Would you like a water or would you like a soda?”

“Man, forget that,” Clayton said. “I have something I want to tell you.”

In the 11 years since he’d tried Buchanan, Clayton had been a successful prosecutor and civil litigator, and he’d served a brief stint as a district court judge. For many years his attitude was, “You did the crime, you got the full time.” But Clayton also had travails; a doctor whom one of his clients was suing said Clayton threatened him with a criminal investigation in order to leverage a civil settlement. Clayton was arrested and booked, charged with criminal extortion. The case fell apart, but it gave Clayton a glimpse of what it was like to be targeted. “It taught me that even I, as a prosecutor, can be subject to people wrongfully coming after you,” he says.

Then in 2004, he prosecuted a serial killer, Derrick Todd Lee, whose DNA was linked to the murders of seven Louisiana women. Lee was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to life without parole—the same as Buchanan. Clayton learned, he said, “what murder truly is,” and found himself believing that life without parole should be reserved for the Derrick Todd Lees, not the Taurus Buchanans.

That night at the tournament, Clayton told Buchanan that if anybody deserved a second chance, he did. He said that if Buchanan should ever get any kind of hearing, he would speak in his favor.

Clayton says that when he ran into Buchanan that evening, the sight of a mature, respectful, measured young man reinforced the doubts he had been harboring for a long time: “He’s a different man than the kid that I saw.” If he had it to do over, Clayton says, he would present a plea deal for manslaughter. “I would offer him 21 years—and let him do 7,” he says. “I should not have prosecuted Taurus for murder. I think I went too far. If the state of Louisiana lets him out, I would fall on my knees and thank God.”

Buchanan’s life sentence also rests uneasy with at least two of the jurors who voted to convict. Leigh Gilly was a 22-year-old college student when he served on the jury. Now in his 40s, he has four kids—one the same age as Buchanan when he threw that punch. “I’ve thought more and more that he shouldn’t be in prison for life probably because he was so young,” Gilly says. “At 16, we just aren’t who we’re going to be.”

Briley Reed was also 22 when Buchanan stood trial. He was one of the jury’s two African Americans, both of whom voted to convict. “After the decision was made, I still thought about it all the time. It took me a while to get it out of my system, because it was still haunting me,” Reed says. He, too, wishes Buchanan had a chance at parole. “Because he served his time,” Reed says.

The most recent of the cases before the Supreme Court may, in fact, force Louisiana to reconsider Buchanan’s sentence. In 2015, the Supreme Court heard a case—out of Louisiana—on whether states can be compelled to apply the Miller ruling, which declared mandatory life-without-parole sentences for juveniles unconstitutional, retroactively.

During oral argument in October, Michael Dreeben, a deputy solicitor general appearing on behalf of the Justice Department, told the court that not only have some states—the majority, he added—reopened their cases, but so has the federal government. And in the federal cases, he said, “those defendants have almost uniformly received sentences that are terms of years significantly shorter than [life].”

The justices’ decision will likely come down in 2016. Henry Montgomery, the case’s petitioner, was convicted and sentenced in East Baton Rouge Parish when he was 17. He is now 69.

Jacques Brown’s aunt, Joann Phillips, has Taurus Buchanan frozen in her mind as a 16-year-old. “How old is he now?” she asks us. Told the answer—Buchanan is 39—she says, “He’s that old now? Oh my God…My heart goes out to him, because even though my nephew is gone forever, forever, forever.” Her voice trails off. Then, moments later, she says: “I forgive him. I forgive him. I just say, let him go.”

After Jacques was killed, his mother, Janice, would sit in the house and stare at the front door for hours, waiting for him to come home. Not long after, she turned to drugs. But she is sober now, and has been for years.

In October, she said of Buchanan: “I don’t know how they can see that that child should be out of jail when he took somebody else’s life.” But a few days later, on a balmy Saturday afternoon, she went to the cemetery where Jacques is buried. For about an hour, she walked the grounds. When she returned home, something had shifted. She acknowledged that her sister was right. “Holding on to tragedy for a long, long time is not good,” she said. So she changed her mind. She forgave Taurus.

After this story was published in the January/February 2016 issue of Mother Jones, Taurus Buchanan was informed that he would be granted a clemency hearing. He first applied in Oct. 2014. The hearing will be held on Feb. 16.