A s a prison nurse, Domenic Hidalgo had access to prescription medication, a highly coveted commodity among the inmates at the Clements Unit in Texas, the state prison where Hidalgo worked.

He tried to use that access to get what he wanted: sex with Matthew, a prisoner at the facility. When Matthew reported Hidalgo’s advances to prison staff in April of 2011, officers wired him with a recording device and told him to prove it.

In audio obtained by The Marshall Project, Hidalgo can be heard handing Matthew a Bupropion pill, a type of antidepressant, and asking to perform oral sex on him in exchange. “This is the best time,” said Hidalgo, but Matthew demurred, saying he’d come back soon. “Let me just mess with you,” Hidalgo insisted. He then pulled down Matthew’s pants and masturbated him. (The full names of victims have been withheld to protect their privacy.)

In Texas, sexual contact between staff and inmates is a felony, punishable by up to two years in prison. Combined with an additional felony charge for distributing drugs to an inmate, Hidalgo was facing up to 10 years behind bars. But Hidalgo avoided prison altogether. In 2013, he pleaded guilty in exchange for a $500 fine and four years on probation. If he stays out of trouble, his felony conviction will be removed from his criminal record in 2017.

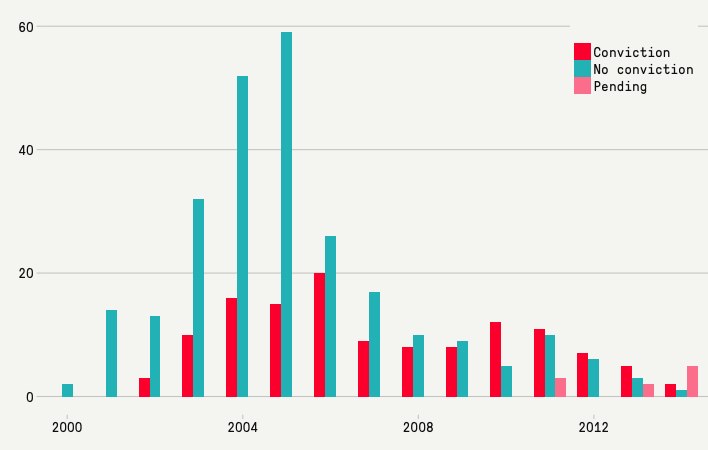

The plea deal Hidalgo received for sexual contact with a prisoner is typical in Texas, and illustrates how rare it is for prison staff there to be imprisoned for sexually abusing the people in their charge. Since 2000, the state prison system’s inspector general has referred nearly 400 cases of staff sex crimes against inmates to prosecutors. An analysis by The Marshall Project found that prosecutors refused to pursue almost half of those cases. Of 126 prison workers, mostly correctional officers, convicted of sexual misconduct or assault, just nine were sentenced to serve time in state jail. The majority of the rest received fines ranging from $200 to $4,000 and a few years on a type of probation called deferred adjudication, which results in a clean criminal record if conditions are met.

DEFERRED ADJUDICATION — 105

JAILED — 9

PROBATION — 6

OTHER — 6*

PENDING TRIAL — 4

NOT GUILTY — 3

DEFERRED ADJUDICATION — 105

JAILED — 9

PROBATION — 6

OTHER — 6*

PENDING TRIAL — 4

NOT GUILTY — 3

At the Clements Unit, where Hidalgo worked, more prisoners reported being forced, coerced or pressured into sexual contact with staff than in any other male prison in the country, according to a federal survey released in 2013. The Clements Unit is just one of the reasons Texas leads the nation in prison sex abuse. In federal surveys of inmates, Texas has had more facilities deemed “high rate” for sexual abuse than any other state, leading the Dallas Observer to declare Texas the “prison rape capital of the U.S.”

Nationwide, prison staff are the accused perpetrators in half of all reports of sexual abuse in prisons and jails, according to the latest justice department survey, which broadly defines any sexual contact, from unwanted touching to romantic relationships to rape, as “staff sexual misconduct.” Most of these allegations are not substantiated by prison investigators. But even when there is enough evidence to prove a staff member had sexual contact with an inmate, criminal sanctions are rare. Fewer than half are referred for prosecution.

Accountability dwindles further from there. Proving sex abuse in prisons is difficult. An inmate’s word may hold little credibility, and prosecutors often refuse to prosecute. The most common punishment for corrections staffers caught sexually abusing inmates is the loss of their jobs.

G uards, nurses and other prison staff have almost complete control over the lives of people who are incarcerated. That power dynamic has led to state and federal laws that identify any sexual contact, regardless of consent, as criminal, similar to protections for the young and people with disabilities.

Such protections for inmates are relatively recent. Change began in Texas in 1996, when a fed-up prosecutor named Gina Debottis lobbied the legislature to enact new laws. At the time, she was prosecuting David Taylor, an employee at the Murray Unit, a women’s prison in Gatesville, Texas, who was charged with using threats to force multiple female prisoners to perform sex acts. “The women had to go in and ask him about their parole plan, and that’s when he would proposition them,” said Debottis. “He would tell them, ‘I know where you live. I can blow up your kids.’ And it scared those women to death. So they were willing to do anything.”

Other women held at the facility also testified that they were abused. Taylor claimed consent. “They initiated it,” he said at his trial, according to the Associated Press. He faced up to 20 years in prison, but the jury believed Taylor and found him not guilty.

“I was sick about it. I felt like justice wasn’t really done,” said Debottis. She used Taylor’s case to pressure the legislature for change, and in 1997, a bill passed that made any sexual contact between prison staff and inmates illegal, whether the prisoner consented or not. Debottis went on to become executive director of the Special Prosecution Unit in Texas, a unique agency dedicated to prosecuting crimes that occur in prison, and the law she pressed for was used repeatedly to convict staff members and sentence them to probation. “It’s another tool in the prosecutors’ tool box,” said Debottis. “If they get probation, it’s still better than prosecuting under the old law, where we had nothing.” Staff convicted under this law are not required to register as sex offenders.

In the late ‘90s, that new view of staff sexual misconduct as a crime in Texas was taking hold in legislatures across the country. In 1990, just 18 states had laws expressly prohibiting sexual abuse of inmates, but by 2006, such laws existed in all 50 states.

Not only did sex between staff and inmates become illegal in recent decades, in many places, it became a serious crime, at least on the books. The federal government raised staff sexual misconduct from a misdemeanor to felony offense in 2006, and with that change, prosecutors went from accepting 37 percent of staff sexual misconduct cases to 49 percent. Sexual contact with prisoners by staff is now a felony offense everywhere but in Iowa and Maryland, where it remains a misdemeanor.

Pressure to put an end to sexual abuse and misconduct by staff was further bolstered by the passage, in 2003, of the federal Prison Rape Elimination Act, which called for “zero-tolerance” toward sexual abuse of any kind in detention facilities and established a set of standards for prevention and response. But there’s little in PREA addressing prosecutions of staff.

“There was a sense that we couldn’t control prosecutors,” said Brenda Smith, a former member of the National Prison Rape Elimination Commission, which formed to make recommendations about implementing PREA. In most parts of the country, local district attorneys take these cases at their discretion. Given this patchwork process around the country, the PREA commission suggested adopting a rule that jails and prisons seek written agreements with local prosecutors, to encourage the pursuit of criminal charges. But the Justice Department ultimately declined this recommendation, saying it would cause "significant burdens,” particularly on resource-strapped counties and municipalities. This was a “missed opportunity,” said Smith. “Those prosecutions — either the threat or promise of them — is an important weapon.”

PROSECUTION DECLINED — 46%

State or local prosecutors decided not to take these cases to a grand jury.

INDICTED — 35%

After an indictment, these cases went on to other court proceedings. In two cases, prosecutors have agreed to pursue an indictment but have not yet taken the matters to a grand jury.

FAILED TO INDICT OR

CASE DISMISSED — 19%

In these instances, either a grand jury did not find cause to pursue or a prosecutor or judge dismissed the charges outright.

PROSECUTION

DECLINED — 46%

State or local prosecutors decided not to take these cases to a grand jury.

INDICTED — 35%

After an indictment, these cases went on to other court proceedings. In two cases, prosecutors have agreed to pursue an indictment but have not yet taken the matters to a grand jury.

FAILED TO INDICT OR CASE DISMISSED — 19%

In these instances, either a grand jury did not find cause to pursue or a prosecutor or judge dismissed the charges outright.

Despite this evolution in policy, sexual abuse by staff continues. In 2013, an officer named David Tatarian was arrested on felony charges he had sexual contact with four women at the Crain Unit, in Gatesville, Texas. Gatesville is the same city where David Taylor’s acquittal on sexual assault charges, and his successful use of consent as a defense, inspired the outrage that changed the law almost 20 years ago. (Gatesville is home to five of the state’s 14 women’s facilities.)

Unlike Taylor, Tatarian could not claim consent, and in November 2013 he pleaded guilty to two felony sex charges. He received 5 years’ probation, a $500 fine, and 500 hours of community service. Like most prison staff prosecuted in Texas, he reached an agreement with prosecutors stipulating that if he meets all the court’s conditions, his convictions would be cleared from his criminal record. But shortly after his conviction, Tatarian stopped showing up for probation meetings and community service and a warrant was issued for his arrest.

“I’m disappointed that things didn’t clean up,” said State Representative Jessica Farrar, a Houston Democrat who introduced the bill that removed consent as a defense for guards who have sexual contact with inmates. “But all we can do is put the law into place.”

S ince the 1970’s, when equal employment legislation took hold, women have increasingly joined men in guarding prisoners of the opposite sex, a development that has led to a notable shift in the demographics of sexual misconduct. It has also made made prosecution trickier.

Women are disproportionately sexually abused by prison staff. Nationwide, they represent 7 percent of all prisoners, yet they account for 33 percent of staff-on-inmate victims, according to the latest Justice Department study.

But female staffers also are the accused in the majority of sexual misconduct cases in prison. That fact has made consent a more complicated issue for prosecutors to deal with in cases where women are the alleged abusers. Women were the perpetrators in two out of three substantiated sexual misconduct cases in Texas, according to the state’s PREA reports. At least part of that can be attributed to sheer numbers. Men make up 91.5 percent of prisoners in Texas, and are overseen by a state correctional workforce that is 40 percent women.

Celeste Bourland was one of those officers. Bourland’s sexual relationship with Shawn, who was incarcerated at the Clements Unit, unraveled when prison officials found a love letter in her car in 2010. “You mean the world to me,” begins the note from Shawn. But the tone quickly changes, as Shawn accuses Bourland of involvement with another inmate. He concludes his note with a request for $500 and tobacco, which he suggests she tuck inside a maxi pad. “I love you!!! Your Husband! :)”

Bourland said in a recent interview that Shawn “had me in his web and under his control,” despite the fact she was the keeper and he was the kept. It’s often hard to see incarcerated men as victims in these situations, said Mark Edwards, the executive director of the Special Prosecution Unit. “I would probably hold a male [officer] who has sex with a female inmate a little more accountable than I would a female [officer] having sex with a male inmate,” said Edwards. “It’s a double standard, but I’m sort of old school I guess.”

When confronted, Bourland admitted she had had oral sex with Shawn. She says she was assured by the prison’s investigator that she wouldn’t be prosecuted. “He made it very clear it would be taken care of, and that there was nothing for me to worry about,” said Bourland, who was shocked when she was arrested unexpectedly two years later. Court documents from the case include a resignation form, purportedly filled out by Bourland, which cites “personal reasons not related to the job” as the reason for the end of her employment as a Texas state prison guard.

According to Texas PREA reports, resignations are exceedingly common; 71 percent of staff found to have had sexual contact with inmates since 2005 resigned before an investigation was complete, and another 8 percent were permitted to resign after the investigation. A spokesman for the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, Jason Clark, said the department has procedures to ensure that staff found to have had sexual contact with inmates are not rehired in Texas. But with a clean criminal record, it’s possible that staffers could find corrections jobs in other states.

Aside from sexual misconduct, Bourland admitted she also smuggled in tobacco, money and jewelry for Shawn. She pleaded guilty to one felony charge of sex with an inmate, and received a $1,000 fine and three years probation. Prison time in cases like Bourland’s would not be appropriate, said Edwards. “When someone’s had to stoop to having sex in a prison with an inmate, things have to be pretty bad in your life,” Edwards says. Juries have even acquitted female staff despite believing they were guilty, he said, noting that in his opinion, harsher penalties wouldn’t change the frequency of these crimes. “They’re not thinking about the consequences.”

One such consequence is a serious threat to prison security. Earlier this month, Joyce Mitchell, a staffer at an upstate New York prison, was charged with aiding the escape of two murderers; it has been reported that she had a sexual relationship with one of them. Female officers played a key role in crimes committed inside the Baltimore City Jail, where a leader of the Black Guerrilla Family gang impregnated four guards. Court filings state that gang members targeted the women they thought they could manipulate, those with "low self-esteem, insecurities and certain physical attributes.” Some of these officers aided in a smuggling operation run by inmates at the jail by sneaking in drugs and cell phones.

In prison, it’s not always clear who is manipulating whom. In September of 2012, Gregory, who was incarcerated in the Coffield Unit in Texas, was caught with a cell phone that contained two videos of him having sex with Carolyn Johnson, a corrections officer. Gregory claimed he took the video so he could use it as evidence to get out of the relationship. “It was like I was married to the mob,” he wrote in a statement to investigators. “I felt if I could provide information to the authorities they would help and even protect me… But then I felt they wouldn’t because I’m just an inmate.”

Johnson was sentenced to two years’ probation, with the possibility of having her criminal record purged, and fined $500.

I n some ways, Texas is at the forefront of prosecuting sexual abuse in custody. It’s the only state in the country with an agency dedicated to prosecuting crimes committed in prisons, and for that reason, the sanctions imposed on prison staff are centrally located and easier to analyze than in most other states. In 2002, fewer than 20 percent of cases involving staff prosecuted for sex crimes with prisoners resulted in convictions. In 2012, that had risen to 54 percent.

It’s unusual, however, for those prosecutions to result in jail stints. One outlier is a case from 2009, when an inmate named Merijildo, incarcerated at the Allred Unit, told Texas prison officials that an officer, John Klyce, had sexually assaulted him 18 times in five years, according to court records. One of those times, when Klyce wasn’t looking, Merejildo spit his DNA into a t-shirt and saved it.

Merejildo told investigators the sexual exchanges with Klyce had escalated over the years, from requests to demands and threats. He told investigators he came forward because he was getting released soon and wanted to protect the other prisoners. Klyce denied the allegations, but once the DNA evidence was disclosed, he admitted to a single sexual encounter. He blamed Merejildo, saying he had come onto him by talking “dirty.”

While consent was removed as a defense for corrections staff in Texas decades ago, it still plays a role in most prison sexual abuse cases, at least informally. Klyce claimed consent and eventually pleaded guilty to a felony charge of improper sexual activity with a person in custody, a charge used for sex that is not forced or coerced. In recent years, Texas officials have increasingly relied on this lower-level charge, while sexual assault, which carries harsher penalties and is more difficult for prosecutors to prove, has been used less often. Klyce was sentenced to 180 days in jail.

It’s the same charge nurse Domenic Hidalgo received after using drugs to solicit sex with Matthew, who was incarcerated at the prison where he worked. Hidalgo had been sexually pursuing Matthew for months, using drugs to attempt to seal the deal, and was “persistent,” according to Matthew’s statement to investigators. He wanted to prove that he was telling the truth.

And he did.

After Hidalgo touched Matthew, they arranged to meet in a downstairs bathroom. But instead, Matthew went looking for the officer who had wired him up just a half an hour earlier. In that time, Matthew had been handed drugs for sex, just as he claimed. “I got it,” he whispered as he handed over the recorder to an officer. “It’s all on tape.”