I. “A Modern-Day Plantation”

Six years ago, amid the cotton fields of South Carolina, a stabbing spiraled into America’s deadliest prison riot in a generation. The next morning, it fell to a prisoner at Lee Correctional Institution named Ofonzo Staton to start mopping up the blood.

As he lifted body bags onto gurneys, the 41-year-old father found himself judging the young gang members whose rampage had killed seven men and injured many others. “If you’re going to be angry,” he recalled thinking, “be angry against the oppressor!”

In media reports, state officials largely attributed the violence to gang rivalries and contraband cell phones. But after two decades inside, Staton — who goes by “Zo” — could talk like an anthropologist, describing how endless sentences, meager medical care and moldy food had spawned hopelessness and rage among the mostly Black population. The prison itself bore the name of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee, leading another man inside to call it “nothing more than a modern-day plantation.”

So it was all the more jarring to see cheery flyers, posted around the prison soon after the riot, inviting men to apply for a new unit called “Restoring Promise,” where residents ages 18 to 25 would supposedly find “a right to privacy, self-expression, and connection with family.”

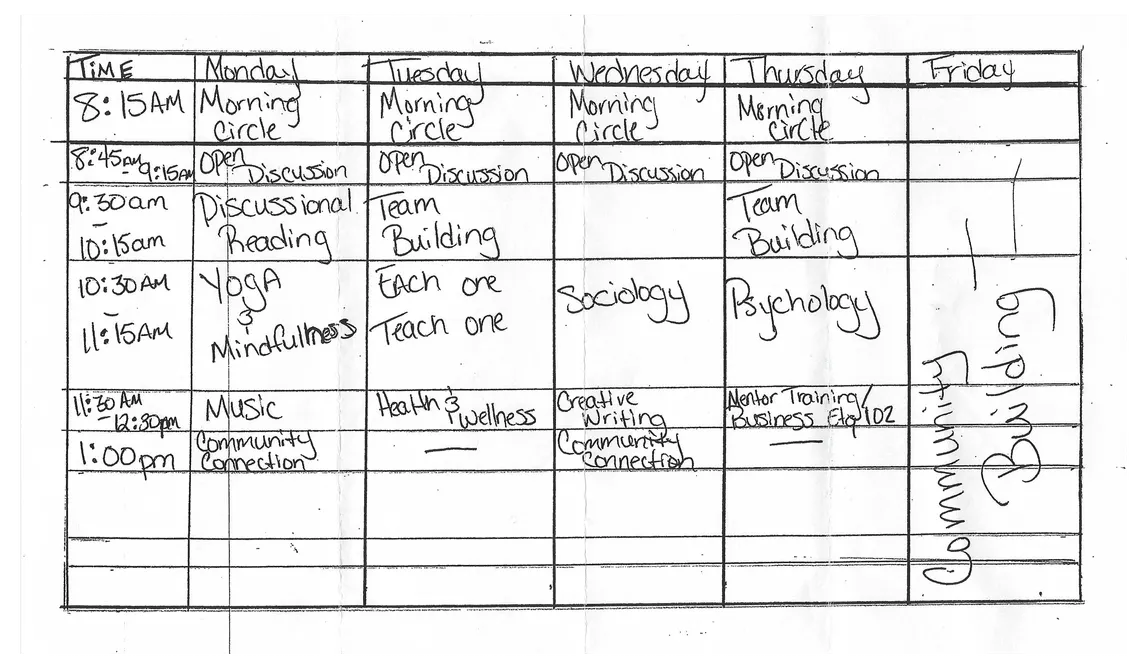

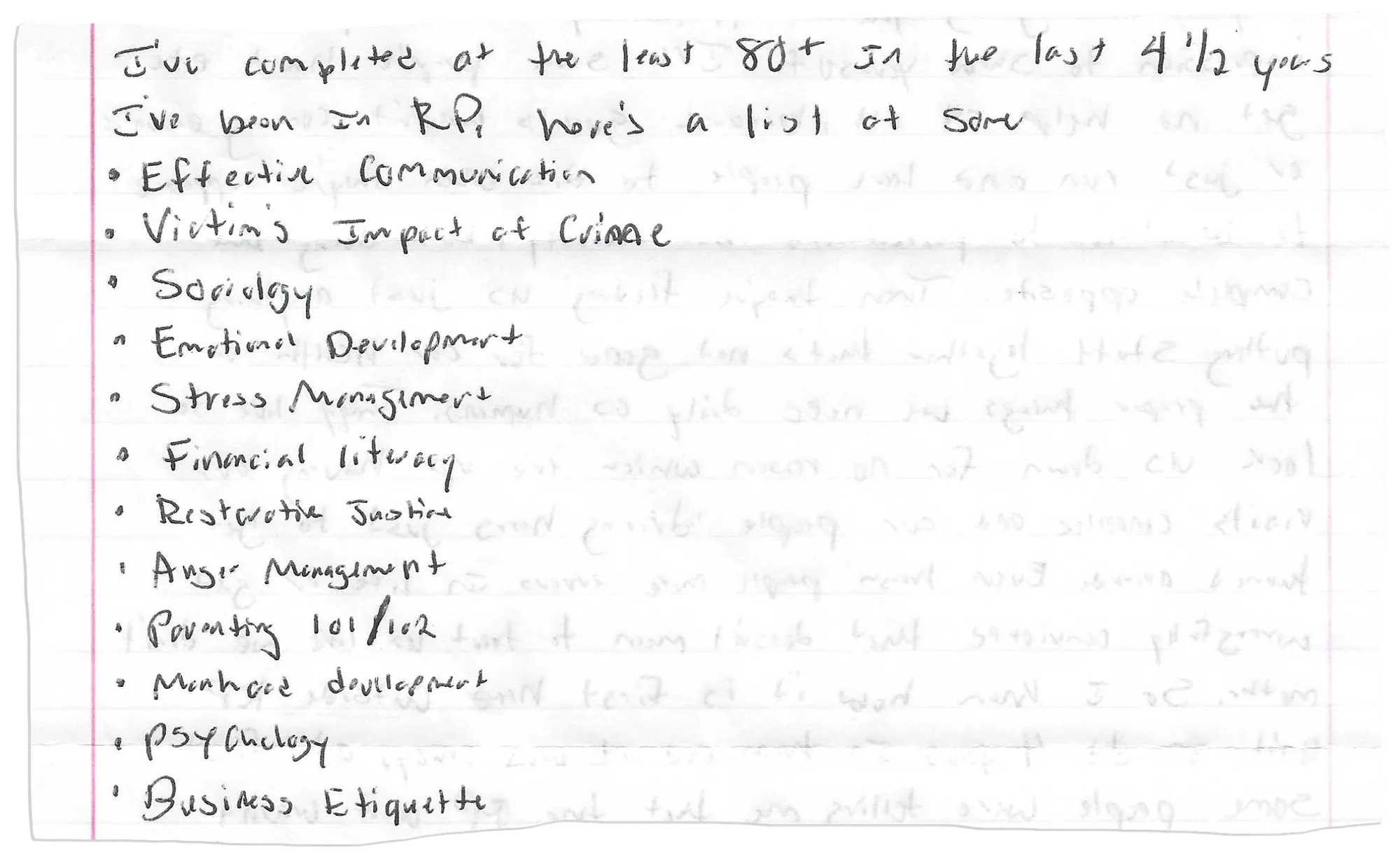

Staton had seen programs come and go, but this one seemed radical. The concept drew on German prisons, where people have individual cells they can personalize, and officers act more like counselors. In the new unit, older men like Staton would serve as mentors. They would design the living environment and teach classes on everything from financial literacy to parenting. They would also write the unit’s rules, and decide together how to treat rulebreakers.

For Staton, Restoring Promise was a chance to share the wisdom he’d earned over 21 years inside. The Marlboro County native was doing life for helping a cousin murder a woman, but he always maintained his innocence and never stopped filing appeals.

“I said early on I wouldn’t conform to prison, because I wasn’t trying to stay there,” Staton said in an interview last fall. If someone asked when he was going home, he’d respond, “Probably tomorrow!”

But underneath that carefree attitude, Staton constantly worried about his son, Ja’Kirus, who was born less than a year before his arrest. Visit by visit, he’d watched the squirming toddler grow into a hot-headed teenager who he worried might be drifting toward prison himself.

This new unit couldn’t help Ja’Kirus, but it would give Staton a chance to guide men his son’s age and plant something he could leave behind. Staton didn’t know it at the time, but he would soon be released. He also had no way of knowing how much his work would matter to the future of American prison reform.

II. Searching for Solutions in Germany

Restoring Promise is a national initiative led by the Vera Institute of Justice, a New York-based nonprofit that partners with states on criminal justice reform programs. The first unit launched in Connecticut, a blue state, in 2017 — a moment when public officials across the left and right were talking about making prisons more rehabilitative. Soon after, Vera received applications for the program from several red states, including South Carolina.

But shortly after the Lee unit opened in 2019, the pandemic-era spike in serious violent crimes and the tumult of the George Floyd protests made talk of change more politically perilous. In this context, Lee was a testing ground: If a program designed to give incarcerated people more control over their lives could blossom there, perhaps there was hope everywhere.

The seeds of Restoring Promise were first sown in Germany. In 2015, the Vera Institute took a group of American prison officials, prosecutors and researchers to visit the country’s rehabilitation-focused lockups, where people can serve fewer than five years for violent crimes. I tagged along.

Everyone on the trip had a favorite detail. Some were drawn to the therapeutic horses and rabbits in the idyllic barns of rural Neustrelitz Prison. Others raised their eyebrows at the kitchens full of knives. But I kept noticing the toilets.

Unlike the metal we typically use in the U.S., the German toilets I saw were made of smashable white porcelain that American officials would consider a security risk. They were also enclosed in private bathrooms instead of being exposed to passersby. These small choices conveyed a sense of dignity that people on the outside take for granted.

In the United States, a disproportionate number of incarcerated people are Black or Latino. In German prisons, people born abroad — mainly in the Middle East and Eastern Europe — are overrepresented. But my trip mate Khalil Gibran Muhammad, a Harvard University historian who studies racism and crime policy, noted how this inequity didn’t produce decades-long, hope-killing sentences. “The point was that nobody spends a lot of time in their prisons, no matter who they are.”

Muhammad asked our guides about the origins of their approach, and they described how, following the Holocaust, the Federal Republic of Germany adopted a new constitution that declared human dignity “inviolable” and required “all state authority” to “respect and protect” that dignity. Unlike the U.S. constitution, which still allows “slavery and involuntary servitude” for people convicted of crimes, Germany’s Basic Law doesn’t formally exclude incarcerated people.

For Muhammad, the lesson was that a society can’t truly move forward without reckoning with its history and transforming its culture. He also noted an irony: U.S. officials had pushed Germans to see themselves as collectively guilty in the aftermath of the Holocaust, in a way Americans themselves never had done with slavery. “We’re the most powerful country, and govern ourselves by a double standard,” Muhammad said.

Our trip mate Scott Semple, then the commissioner of the Connecticut Department of Correction, was struck less by these historical differences than by what the two countries share today: young adult prisoners who need help with their impulsivity. In Germany, these young men and women received more intensive therapy, based on the idea that the human brain remains especially receptive to change before age 25. (The youth prison we visited was also co-ed; we even saw a young couple kissing in public.)

Back in Connecticut, Semple ordered his staff to develop a unit for young men that would enlist older prisoners as mentors. In 2017, when I toured Connecticut’s Restoring Promise site at Cheshire Correctional Institution, I was struck by how these older prisoners had found purpose in preparing young men for release. “Some of us have taken lives, so it’s only fair that we try to save lives,” mentor John Pittman said at the time.

Over the next few years, Connecticut expanded the program to York Correctional Institution, a women’s prison, and more Restoring Promise units sprang up in Massachusetts, Colorado and North Dakota.

Around the same time, other prison reformers were taking cues from Norway, which also “normalizes” prison environments to mimic the outside world. After touring Norwegian lockups, Pennsylvania corrections officers created “Little Scandinavia,” a special unit at State Correctional Institution-Chester where residents can shop for groceries online, cook their own meals, and even dine with officers.

Amend, a health-focused group based at the University of California, San Francisco, used Norwegian principles to train corrections officers from several states to better address the psychological needs of people in their custody. These efforts garnered the praise of California Gov. Gavin Newsom and federal prisons Director Colette Peters. One Voice United, a national corrections officer advocacy group, lauded how their Norwegian counterparts manage far fewer prisoners and receive two years of training, rather than the few weeks common in the U.S.

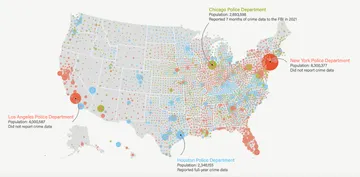

Despite the buzz, these experiments remain drops in the ocean of America’s prisons and jails, which hold nearly 2 million people, often under conditions that can make the word “corrections” feel like a cruel joke. For all the tax dollars spent on them, U.S. “correctional facilities” seldom address the underlying problems — from a thin social safety net to rampant inequality — that drive crime.

Prison agencies typically measure their performance by recidivism — whether the people they release are arrested or locked up again. Even by this metric, American correctional facilities do a poor job: A recent federal analysis found that 82% of people released from state prisons were re-arrested within a decade.

At the same time, programs like Restoring Promise must prove their value to maintain funding and withstand changing political views. Ever since the 1970s, when the sociologist Robert Martinson popularized the phrase “nothing works” in regard to prison programs, nonprofits and academics have struggled to prove that these efforts can reliably bring down arrests or convictions. But more recently, some researchers have begun to question if the problem is the focus on recidivism itself, which fails to account for problems people face when they return home.

These questions may sound academic, but they’re actually about politics and money: Prison programs have to convince philanthropists, who spend hundreds of billions each year on healthcare and education but devote less than 1% of their funding to criminal justice. Such programs are also at the mercy of lawmakers and voters, who are as torn as ever about the purpose of prisons. Are they supposed to be punishing people or rehabilitating them?

III. Building a New Unit, Step by Step

To develop the Restoring Promise curriculum, the Vera Institute partnered with MILPA, a California-based collective of formerly incarcerated Native American, Black and Chicano activists, to teach concepts like restorative justice and intergenerational leadership. After working in Connecticut and Massachusetts, the nonprofit staffers knew South Carolina would be different. “My first image is driving up to Lee and seeing all the cotton fields, all the Confederate flags in front of peoples’ houses,” said MILPA deputy director John Pineda, who spent much of his youth in California lockups.

Pineda had once worried that reform programs like Restoring Promise would undermine his larger abolitionist goal of getting rid of prisons altogether. But he eventually decided, “If we don’t engage in this process, someone else will.” He bonded with Staton, the older prisoner already mentoring young men, on how to quell the “toxic masculinity” that they’d seen develop behind bars.

In the summer of 2018, Vera, MILPA and the South Carolina Department of Corrections co-created the state’s first unit, at Turbeville Correctional Institution, where shorter sentences would allow mentors to reach a lot of young men quickly. At both sites, prison staff picked the mentors. Young men applied to be mentees with letters about their personal goals, and those who qualified were picked randomly.

By March 2019, all of the Restoring Promise participants had moved into their individual cells, which they were allowed to decorate extensively. Although they weren’t allowed to wear their own clothes like their German counterparts, they traded in orange jumpsuits for khakis and blue button-up shirts. They wrote house rules: no sagging pants, no do-rags before 4 p.m., no gossiping.

To strengthen the mentees’ relationships to their families, the prison administration let parents, siblings and children enter the units and bring in personalized bedspreads. “We’d all sit in this living room area and take turns helping make each others’ beds,” Staton recalled. “We’d eat together, play games, even dance. It gave family members a sense of comfort.”

Under MILPA’s guidance, the mentors handled small infractions — like mentees tussling with each other or possessing contraband — through restorative justice circles. They’d sit and discuss how to make amends, often through formal apologies and extra chores or classes. These infractions wouldn’t affect their institutional records or result in the loss of phone calls or family visits.

But there were limits: If you stabbed someone, you still might still spend time in isolation, which the state calls “disciplinary confinement.” Some young men who repeatedly broke rules were asked to leave.

Many prison staff told me they were skeptical at first, but slowly warmed to the program. Among them was former Turbeville warden Richard Cothran, who spent most of his career with a punitive mindset but eventually came to question it: “Nobody ever said ‘Remember when I lashed out, and you put me in solitary confinement? That really helped!’”

Cothran, who retired in 2019, said most programs in the past only helped men who wanted to change. For the young prisoners with behavior problems, “there was never buy-in, probably because it was created by some old White guy in a room like me, who meant well, but the young men could see right through it.”

To give Restoring Promise the best chance of success, Cothran said he personally asked leaders of prison gangs — the Bloods, Crips and Aryan Nation — to let their members join the unit. Over time, he was struck by how relations between the officers and residents grew less tense. And families of the young men noticed growth. “Parents who had basically given up on their kids came to me and said, ‘Wow, I can’t believe this is really my kid!’”

IV. Meeting the Mentees

One of the first things I noticed when I visited the Turbeville unit last November were the walls covered with vibrant murals of nature scenes and civil rights leaders. (A former staffer described the previous paint colors as “battleship gray and dookie brown.”) At both Turbeville and Lee, mentees’ cells were full of items prisons don’t typically allow, like potted plants and an electric piano.

The South Carolina Department of Corrections does not allow journalists to report incarcerated people’s last names, and most of my interviews were monitored by staff. But even in short conversations, the mentees sounded like they’d been through a lot of therapy.

Aaron, a 24-year-old at Lee serving life for murder, told me when he first arrived in prison at 19 he noticed how men would brush his arm while talking. He saw it as a way of invading his space, to test whether they could take further advantage of him.

Restoring Promise mentors taught him how to be assertive without violence and defuse tension with humor. Recently, when another man had gotten too close, he blurted out, “Come on with that predator shit!” Then he walked himself back: “Damn, bro, this head of mine, you never know what’s going to come out of my mouth.”

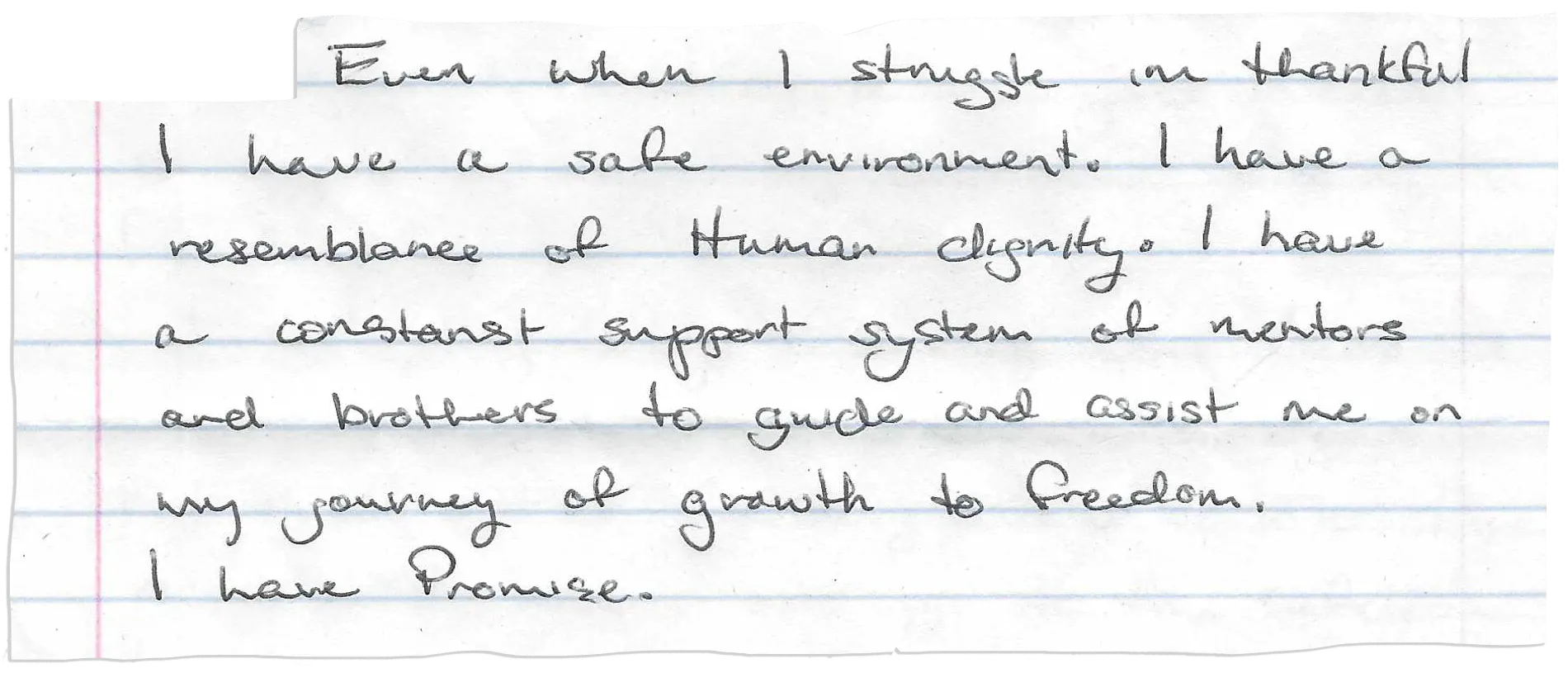

Aaron told me that when the mentees interacted with the general population — in the rec yard and food hall — they had to deal with outsiders calling their program “police shit” and tempting them away with the promise of more free time and easier access to drugs. But Aaron knew if he didn’t choose self-improvement, prison would only train him “to be a better slave.”

Encouraged to be vulnerable, the men agonized over their past choices. Some traced their crimes to low self-esteem, grief and trauma. Before Aaron was sentenced to life, his stepfather and uncle had died. Unable to talk to these male role models, he bottled up his emotions to avoid being perceived as “crazy.” “Growing up, I never really had a lot of people I could talk with,” he explained. “I cared a little too much about what people thought.”

Sitting next to him, Michael, 26, recalled how — on the path to convictions for manslaughter and armed robbery — he’d taken beatings for his younger siblings. “I didn’t mind being collateral damage, which is not good,” he said. In Restoring Promise, he “realized I had something to live for.” He had recently graduated from mentee to mentor, a role he may hold for a long time; his projected release date is in 2040.

I noticed a tension in these autobiographies. The official line from mentors and prison staff is that the mentees must take unequivocal responsibility for their mistakes if they’re ever going to grow into mature men with positive futures.

On the other hand, the Vera and MILPA trainers discuss systemic issues, like mass incarceration and the 13th Amendment, the part of our constitution that allows forced and unpaid labor for people convicted of crimes. The residents learn about how (mostly) White people with power have made policy decisions that imperil their (mostly) Black lives.

Each mentee I talked to told a story of their life that fused these two visions. Demarea, a 23-year-old at Turbeville, accepted blame for carrying an illegal weapon, but he also said he needed it for protection: “A lot of young Black males were dying in my area,” he said. When he gets out, he plans to distance himself so that he doesn’t need to carry a gun. “I’ve already missed a year of my son’s life,” Demarea continued. “That’s what keeps me up at night.”

Restoring Promise created a space for Demarea to talk about that guilt. Each day, he and the other men stood in a circle to check in. If you had a scowl on your face, someone would ask why.

After meeting Demarea, I watched a Turbeville mentor named Matt shout “Circle up!” and a group of around 30 mentors, mentees and prison staff got into formation. Everyone rated their mood on a scale from one to 10 and shared advice they would give their younger selves: “Listen to my elders,” said one resident. “Carry yourself like someone is watching you,” said another.

V. The Ballad of “Zo” Staton

Touring the South Carolina prisons with Staton meant constantly pausing for staff and residents to embrace him. It was like tagging along with a college alum during homecoming. Only he was never supposed to graduate.

In 1995, Marlboro County prosecutors charged his cousin Johnny Pearson, a mechanic, with the rape and murder of a customer named Darlene Patterson. Several witnesses claimed they had seen Staton at a party where multiple men raped Patterson, as well as on the bridge where her body was found. But these witnesses eventually recanted, and Staton’s cousin signed an affidavit stating he acted alone.

“I was destined to go to prison, innocent or not,” Staton said. But like many of his mentees, he also cast some blame on himself, recalling how his mother had warned him about relatives like Pearson.

Staton knew his son, Ja’Kirus, didn’t blame him for being in prison. But as he watched his boy grow into a man, he began to hear arrogance in his voice. Eventually, Ja’Kirus admitted that he’d joined the Bloods, and was “selling dope, running with the wrong people, fighting, shooting.”

One summer day in 2019, Ja’Kirus, then 25, missed a planned visit. Staton called home the next day. “There ain’t but one way to tell you,” his mother said. “Ja’Kirus got killed last night.”

Staton found an empty room to cry in, and by the time he got back to the unit, the news had spread. “Staff and residents were praying with Zo, bringing him their own meals and canteen food. The other mentors took over his classes and chores,” recalled Brittany Brown, the unit’s program coordinator. “I had never seen this in a prison setting.”

Six months after Ja’Kirus’ killing —which remains unsolved — Staton applied for parole. He’d been denied many times before, but this time his peers wrote letters extolling his mentoring skills. And, to his surprise, the lead prosecutor from his case wrote a letter describing his involvement in the crime as “minimal.”

In February 2020, the parole board agreed to release Staton. Soon after, lawyers at the North Carolina Center on Actual Innocence agreed to help him seek exoneration. They’re still investigating his case.

On April 7, 2020, Staton returned to his mother’s house in tiny Bennettsville and found a welding job. After a few months, MILPA hired him as a researcher. They would teach him how to analyze data about the unit he had helped to create. They certainly needed him, because Restoring Promise was struggling.

VI. Trouble Behind the Scenes

After my visits to the Lee and Turbeville units last fall, I exchanged letters with 10 mentees. Under cover of anonymity, they painted a much bleaker picture than the one I’d gotten. “Prison officials do not want the initiative to work,” wrote one young man. “Our initiative has been set upon by staff sabotage,” wrote another.

Their examples ranged from surface-level (a broken washing machine) to systemic (mentors not being paid for their work). The mentees also said there were often not enough prison staff around. Lockdowns due to problems elsewhere in the facility interrupted their classes and other activities.

Chrysti Shain, the director of communications for the South Carolina corrections department, said there is “enormous support” for the program, and that residents may have failed to fully convey their needs to staff. She attributed understaffing to typical turnover, noting that prisons across the U.S. struggle to recruit and retain workers. South Carolina is trying to fix the problem with better pay and benefits.

But in interviews, some former corrections department leaders described a series of setbacks. They asked the state to pay the mentors, and were denied. (Shain said South Carolina pays people who work for prison industries, but not mentors and peer counselors.) Some of these leaders quit in frustration at the slow pace of growth and said that skeptics took their place. “It’s like it’s in a cocoon, and just can’t come out,” said Virginia Barr, a former department division director who oversaw the units until 2020. Shain explained that COVID-19 had slowed growth and said the agency now plans to expand Restoring Promise to a women’s prison.

Former Vera staffers I interviewed said they were prepared for challenges. But about two years into the South Carolina units, some felt demoralized by post-riot conditions statewide. Two units housing fewer than 100 men between them couldn’t make a dent in a system that incarcerates about 16,000 people and draws frequent complaints of medical neglect and censorship.

In early 2020, Alexandra Frank, then-project director of Restoring Promise, was inundated with calls and emails from activists who said the corrections department had not made good on its promise to remove the metal plates it had placed over many cell windows, blocking out sunlight. The state corrections department said the plates were security measures meant to stop prisoners from signaling to people outside that it’s safe to throw contraband over fences.

Activists pushed back, writing, “The idea of ‘Restoring Promise’ cannot be reconciled with a prison system where thousands of prisoners are not even given reliable daily access to sunlight.” (The state corrections department said they have since adjusted the plates so that everyone gets sunlight.) Frank, who has left Vera, had also tangled with agency leadership over security measures like deploying drug-sniffing dogs at the prisons.

During my visit to the Lee unit, I met Bryan Stirling, the corrections department director responsible for these measures. He recounted how he’d been working as then-Gov. Nikki Haley’s chief of staff when she offered him the corrections job in 2013. At the time, many conservatives were calling for shrinking prison populations, and he recalled Halley telling him, “Most of them are getting out, and we need to make them better than when they came in.”

Stirling signed the state up for Restoring Promise, ramped up job training systemwide, and made it easier for people leaving prison to get driver’s licenses and other documents. The result, he said, is that South Carolina has the lowest recidivism rate in the country. While that’s hard to confirm — states calculate recidivism in different ways — it is true that South Carolina saw a drop in returns to prison, within three years, from 34% for people released in 2005, to 17% for people released in 2020.

As Stirling touted the dramatic drop, Staton stood nearby, nodding along. But later, when we were alone, he rolled his eyes. The number of people returning to prison is so low, Staton said, “because you don’t let nobody go!”

The numbers support Staton’s perception. Reflecting a nationwide plunge, South Carolina released just 7% of its parole applicants last year, according to Bolts. Staton, other mentors, and even prison officials told me it would be much easier to coax young men towards maturity if more earned early release. “We strive to give them hope,” a Lee mentor named Ernest said. “That lasts for six months or a year, but then you wake up, and you’ve got 60 years.”

And the political winds have changed in the state. Haley stepped down as governor in 2017 to work for the Trump administration. Her successor, Henry McMaster, allowed the Restoring Promise units to take root, but he has focused most of his attention on limiting early prison releases and restarting executions. Under his authority, Stirling’s staff recently carried out the state’s first lethal injection since 2011 and prepared a firing squad chamber.

These political realities mark a stark difference from the countries that inspired these units. On my trip to Germany in 2015, Americans asked their officials if they ever felt political pressure to make prison conditions more miserable. They responded with blank stares. The public, they said, trusted their expertise.

VII. The Challenges — and Opportunities — of Self-Evaluation

When it came time for Vera to formally evaluate the national Restoring Promise initiative, researchers were adamant that they would only study the South Carolina sites if the residents gave their consent. As part of a growing trend toward “participatory action research,” they enlisted the men in the program to help code the data.

The study was designed to compare mentees’ behavioral outcomes with young men who didn’t get into the unit due to a lack of space. The scientific goal of a randomized controlled trial was to prevent anyone from cherry-picking the best-behaved young men. Vera researcher Selma Djokovic said the mentors were pleased because it took away some control from the prison officials, who typically dictate their housing assignments.

Released last summer, the study found a 66% decrease in the odds that the mentees would be charged with a violent disciplinary infraction, compared with young men who were not in the program. As with any social science research, there were plenty of caveats: COVID-19 lockdowns had interrupted the family visits and classes that formed the core work of the unit.

Notably, there was no decline in smaller disciplinary violations, like smoking or disrespecting officers. Ryan Shanahan, Vera’s Restoring Promise project director until this past July, hypothesized that the mentees “test boundaries more” when they feel safe, but also may face more scrutiny of their behavior, given that the program is trying to change it.

Perhaps the most important thing about this research was what it wasn’t measuring: recidivism. In other words, Vera chose not to track whether the young men who got released were arrested again. In nonprofit circles, this choice was a declaration of values amid an increasingly contentious debate about what counts as a successful criminal justice initiative.

Restoring Promise has relied on around $2.25 million in federal grants and $7 million from Arnold Ventures, an organization that also grants money to The Marshall Project. The funding comes from John Arnold, an oil, gas and hedge-fund billionaire who looks for proof that ideas work before he encourages governments to expand them. Arnold Ventures vice president Jennifer Doleac publicly feuded with Vera last year over whether their research methods were rigorous enough, amid a larger fear that criminal justice nonprofit funding, which began falling in 2021, will sink further.

But in 2022, Arnold Ventures also funded a report by a group of criminal justice scholars about why recidivism shouldn’t be the main marker of progress. Most measurements amount to a simple yes or no. Someone was rearrested, or they weren’t. They went back to prison, or they didn’t. But these numbers don’t reveal how a person stays out of prison. A woman might not return because she earned a law degree. Or she might have died from a drug overdose on the outside.

Other scholars have pointed out that outcomes can be warped by police, prosecutors and others who decide whether to arrest people and send them back to prison.

Vera staffers see better prison conditions as a moral necessity rather than a numbers game. “Regardless of whether you’re coming back or not, you should be treated like a human being,” said Chloe Aquart, the new director of Restoring Promise.

At the same time, Restoring Promise may be good for an entirely different group of people behind the prison walls: corrections officers. Many have reported “feeling safe and finding purpose in their work” in program surveys.

Vera isn’t alone in focusing on how Europe-inspired improvements might alleviate the burnout that leads many officers to quit. The nonprofit Amend took corrections officers from several states to Norway, showing them how their counterparts there act as healers and counselors.

“Everything that brings someone to prison has to do with health,” said Brie Williams, the medical doctor who founded Amend. “And yet so often what happens inside prisons reduces their ability to make personal change. So how can we train staff to help people change?”

Williams introduced me to Toby Tooley, an Oregon corrections officer who had been struggling with a man who threatened the staff. They put him in an isolation cell, where he smeared feces and hit his head on the walls. But after seeing how Norway uses intensive communication and creative therapies, Tooley’s team used art supplies to calm the man down, allowing him to leave his cell more often.

After working with Amend, both Oregon and North Dakota reported they were using solitary confinement less often, without a rise in violence. Workers like Tooley said in surveys that this improves their own quality of life, but they rely on stories as much as data. “Going to Norway helped me be a better person,” he said.

Part of Staton’s post-release work with MILPA is uncovering these stories. Using the same anthropological sensibility that helped him diagnose the 2018 riot at Lee, he wrote survey questions that explore why violence decreased among the young men. Vera ended its contract with MILPA in June, and MILPA staff cited budget constraints amid a broader decline in criminal justice reform funding. But Staton is still helping to write a study of the Restoring Promise units that will be published by Arnold Ventures later this year.

VIII. A Full-Circle Moment

After my tour of the Lee unit, Staton and I drove to a combination gas station-diner for lunch with a group of corrections department staffers. I had never seen a man break bread with the people who once confined him. But what surprised me most was the way they listened to him.

He and Nikeya Chavous, the director of the state’s division of youth parole and re-entry, had a particularly strong rapport. At one point, they clashed about when families might be able to come into the Restoring Promise, as they were allowed to do pre-pandemic. Staton believed these so-called Family Focus visits should return as soon as possible. Chavous said this wouldn’t be fair to all of the other people in the system whose visits were still restricted.

But this soon gave way to a back-and-forth about history, racism and the cultural challenges they face when trying to reach the young Black men in their care. “If you’re a young Black man, you want to be an athlete or a rapper,” Chavous, who is Black herself, complained as Staton nodded in agreement.

The next evening, I sat with Staton and his mother, Kathey, in her living room. We were talking about his life, his son’s death and the culture of prisons when his mother interrupted us.

“They should have been paying him because he ran the prison,” she declared.

Staton laughed. “They need to let me run it for a little while.”

“Would you?” I asked.

“Nah, I don’t think I want the headache,” he said. But then he started musing on what he’d do as a warden, which he summed up with a single insight: “You’ve just got to show them that you care.”

I wonder what else Staton — who lost so much to our broken prisons, but gained such wisdom about how to improve them — would do if given that power.

Arnold Ventures is a funder of The Marshall Project. Under the terms of its funding, The Marshall Project has sole editorial control of its news reporting.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly spelled Bryan Stirling's first name.

![A piece of notebook paper has this handwritten on it:

We have taken a nuber [sic] of classes such as victim impact witch [sic] gives us an opportunity to reach out to our victims or there [sic] family and apologize to show that we are not in the same mind frame as we were when we commited [sic] our crimes.”](https://mirrorball.themarshallproject.org/ymSDFDYqIak1-KBcYaTG1vwK9BGSGRgIuMC5DzeTUUc/w:2000/aHR0cHM6Ly90bXAt/dXBsb2Fkcy0xLnMz/LmFtYXpvbmF3cy5j/b20vMjAyNDA3MjUv/LVNFTEVDVC1DYXJs/eWxlQ29oZW4ucG5n.webp)