I

In the wake of George Floyd’s murder in 2020, Black Cleveland police Sgt. Vincent Montague crossed the blue line. He marched in the streets, arm-in-arm with Black Lives Matter supporters. And in a rally in front of hundreds of aggrieved community members, Montague spoke about his fear that his two young Black sons would die by the hands of the police. In interviews with local and national media, he described the struggles Black cops face inside their predominantly White police departments. And when local and national law enforcement officers planned a pro-police “solidarity demonstration,” he denounced it publicly as a distraction from police reform.

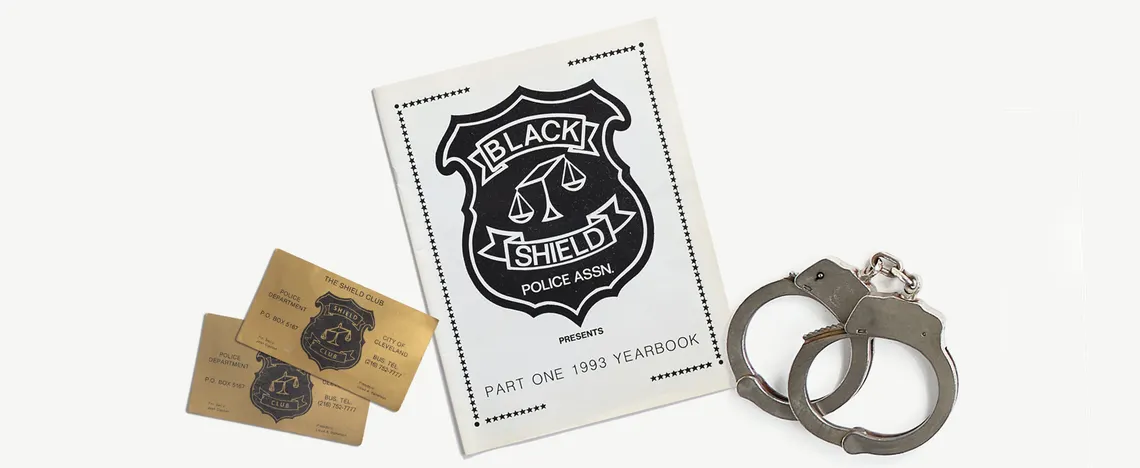

Montague made all of these moves as the president of the Black Shield Police Association. The organization was born in the 1940s as Black officers were rallying around a patrolman named Lynn Coleman, who defended civil rights activists from the violent attacks of private police. Black officers came together to protect Coleman from the racist retaliation of vigilantes and White police. Across the decades, the group has intermittently lived up to the legacy of its inception, agitating for reform and against racism. The summer of 2020, under the stewardship of Montague, felt like one of those times. But of all the controversial appearances Montague made after Floyd’s murder, perhaps the most consequential was on Zoom.

In an online forum about policing, arranged by Cleveland’s bar association, Montague was asked by the bow-tied host whether he agreed with Black Lives Matter protesters that police departments should explore “getting rid of qualified immunity,” which shields officers who harm citizens from civil liability. Montague’s response was frank; some might even say reckless.

“I know that officers are not gonna like it,” he said, wearing an oversized yellow polo that bore the Black Shield logo, “but we need to be held accountable, and we can’t just go rogue and treat the community like they’re nothing. And if these things are going to stop officers from terrorizing the community, or using excessive force, or just overusing their power … I think that we have to minimize that power if the community feels like they’re being violated … Something extreme, something radical, needs to happen for there to be change.”

Montague closed the call by saying, “Whatever I have to do, even if it is going against that code of blue … even if it jeopardizes my safety at work — it’s worth it … if it saves someone’s civil rights from being violated or someone from dying unjustly by the hands of the police.”

The backlash was immediate. The forum host said that several White officers called him up to try to discredit Montague. Supervisors hit him up, too. They described Montague as a “lightning rod.” And Steve Loomis, former president of the powerful Cleveland Police Patrolmen’s Association, sent the Cleveland Plain Dealer a scathing 721-word statement calling Montague a hypocrite who spoke with a “forked tongue,” referring to a time in Montague’s career when he seemed to embody the kind of policing that the BLM protesters he was marching with were rallying against.

While Loomis was ultimately disciplined by the police department for his incendiary public commentary, the implications of his derisive statement troubled me. It wasn’t just that it showed how quickly Montague’s politics made him a pariah. Perhaps that was to be expected. What affected me more was the notion that Montague, the president of the Black Shield, the crusader for police reform, was not all that he appeared to be.

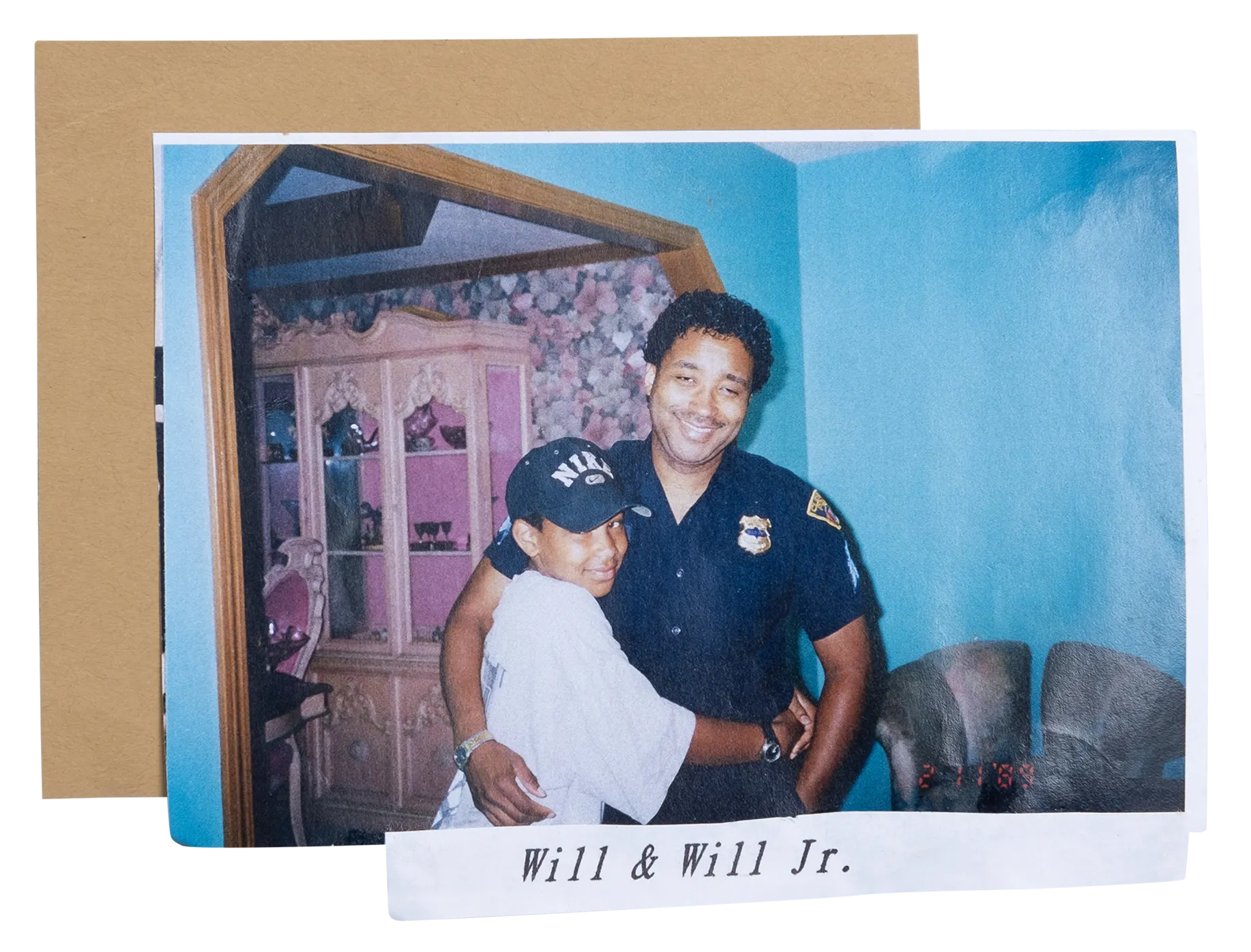

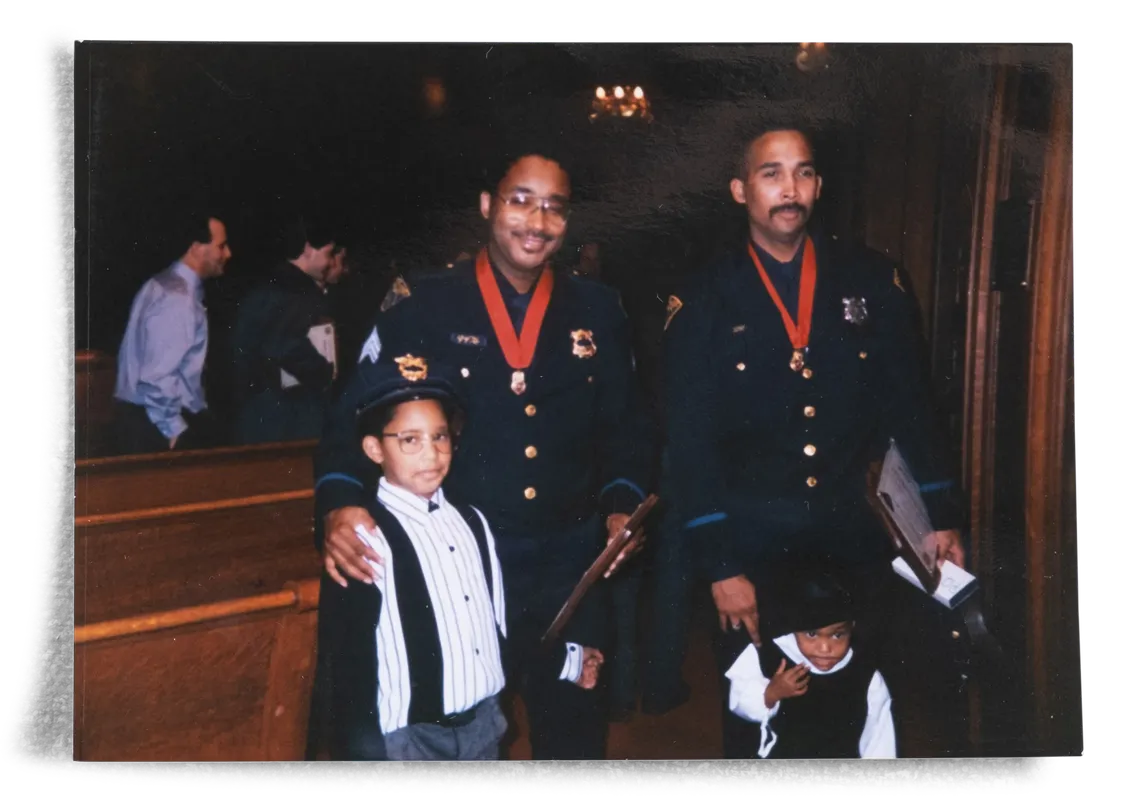

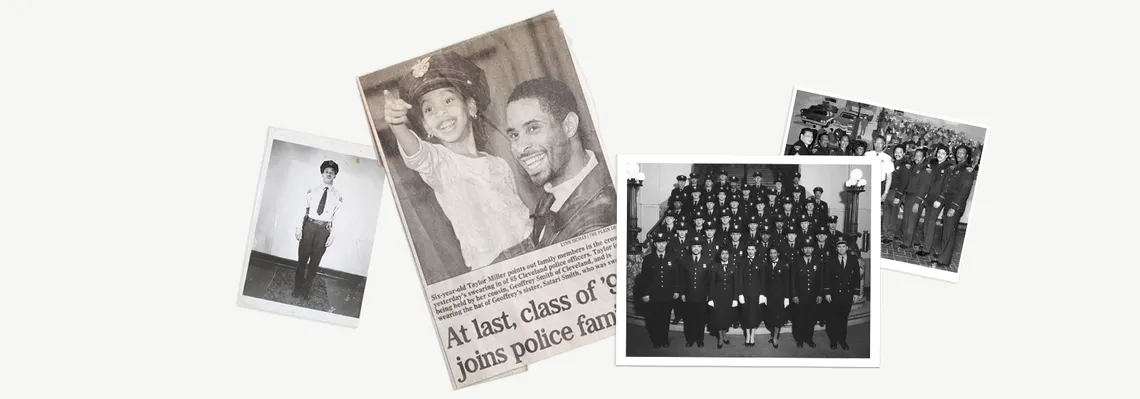

There is a part of me that desperately wants to believe that Black cops like Montague could change law enforcement from within, into something more just. That hope springs from the fact that I have blood in blue. Across three generations, my family members have served as police officers in Cleveland and paid dues as members of the Black Shield, some helping to lead the group and others benefiting from its reform efforts. While I’ve seen how policing can be a crushing and conquering force, snuffing out Black life and liberation, I have always hoped that the presence of people like my parents inside police departments was a positive one. Loomis’ barb against Montague suggested something entirely different: that anyone inside law enforcement, even those oriented toward doing right, could succumb to its worst inclinations.

II

Vincent Montague only had five years on the job when he shot Greg Love.

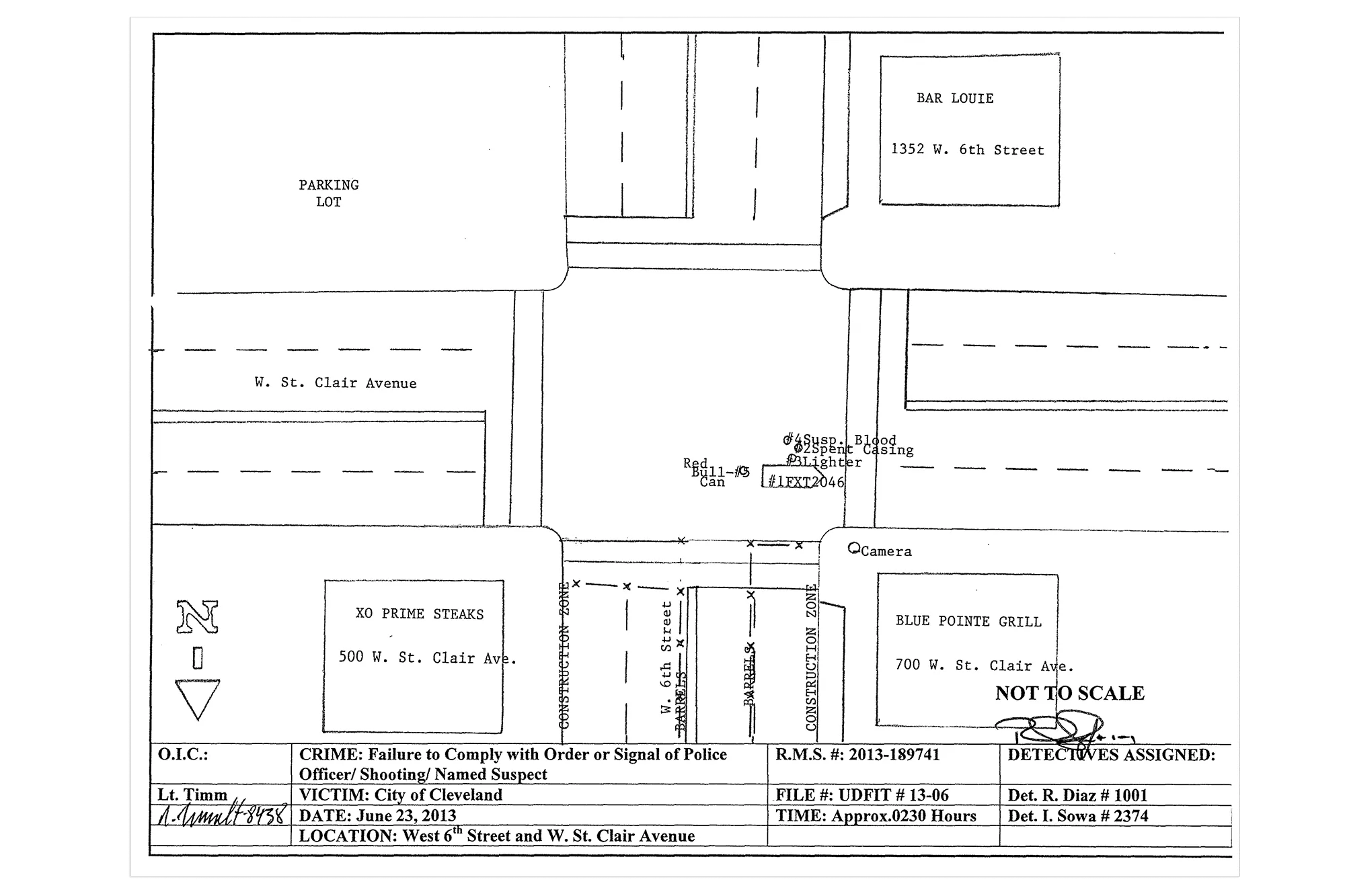

Back then, in the summer of 2013, Montague was assigned to the downtown unit. Every shift was a little bit different, depending on the supervisor. Sometimes he did prison transport. Sometimes he monitored a quiet post with a partner. But on this Saturday night in June, 30-year-old Montague had been given the ludicrous task of directing traffic at St. Clair and West Sixth in the hectic heart of Cleveland’s nightlife scene with only his body and a few dinky orange cones, and he was failing spectacularly.

It was one of the hottest, hypest nights of the year. The Indians had bested the Minnesota Twins at Progressive Field, and Mary J. Blige had just blown the roof off the Quicken Loans Arena, pouring party people into the Warehouse District. Traffic was backed up for blocks, while the sidewalks teemed with weekend warriors, fighting and flirting their way to the next drink.

I grew up in a suburb west of Cleveland and spent a fair share of my young adulthood blitzed at that intersection. It’s always been an easy place to get jammed up. A close friend of mine was hauled off to jail once for merely asking a cop to explain why he was being ushered out of the area while White kids were allowed to just mill about. He’s the privileged, light-skinned son of a prominent local politician. But even he paid an all-too-familiar price for kicking it in the city. In Love’s case, the toll was much higher.

Love and his female friend started that Saturday evening farther west, at a now-defunct airport hotel bar called O’Malley’s. It was the kind of place where bikini-clad barmaids pour Jägerbomb specials. After a while, downtown beckoned. Love hopped behind the wheel of his beefy silver Range Rover with his friend in the passenger seat. Around 2:30 a.m., two cars ahead of Love rolled down West Sixth, past Montague and his pitiful traffic cones. When Love tried to switch lanes and follow suit, Montague jumped in front of his Range Rover, barking for him to back up. Surveillance camera footage shows Love cautiously inching his way back in reverse, before getting caught in the middle of the intersection at a red light amid a sea of pedestrians and cars attempting to cross.

That’s when Montague approached Love’s window, according to reports made by the Cleveland Division of Police’s Internal Affairs Unit and Use of Deadly Force Investigation Team. The southpaw had his Glock out and his finger on the trigger. Confusingly, he ordered Love to put his hands in the air and shut off the car.

Montague later told detectives that Love did not comply, that his hands were down rummaging for something under the seat, with the car still running. Love told a different story. A lawsuit filed against the city, which was settled for $500,000, asserted that Love had put his hands up as soon as he was in the sights of Montague’s gun.

Whatever the case, with his gun in his left hand pointed at Love, Montague reached his right arm into the SUV and began feeling around the steering column to turn the car off. While they may teach a lot of things in the police academy, they probably don’t inform cadets that those tricky Brits put the ignition of Range Rovers of a certain era in the center console. In a 2015 deposition, Montague would claim that while he was trying and failing to cut the engine, Love “tugged” at his gun, and in what he described then as “reactional discharge,” he shot Love point-blank in the chest.

It’s a wonder how these men could end up on opposite sides of an altercation like this. What happened that night, a Black cop shooting a Black man who was unarmed, is just not something that many people expect to see. After all, the fact that Montague even worked for the Cleveland police was due in part to the activism of Black people from previous generations who believed that Black officers like him would police our communities more humanely, more peacefully than White officers.

That’s certainly the notion I heard growing up with a mother and father who were both Cleveland police officers between the 1970s and the 2000s. When grainy footage of another officer killing a Black person would stream across our TV, I’d ask my dad how he could be a cop. Without defending the horror on the screen, he’d talk about the discretionary power he believed Black officers had as gatekeepers at the front door to the justice system. “We can give Black people their citizenship,” he said to me recently. “It may not appear that way, because a lot of us don’t do it. But a lot of us do.”

Some research bears this out. Recent data has shown that hiring more Black officers can lead to fewer stops, arrests and uses of force against Black people. A 2020 study found that while White and Black officers use force at similar rates in White and mixed areas, in Black areas, White cops are five times more likely than Black officers to shoot their guns at people.

Of course, these sorts of studies mean nothing to you when you’re the one pulled over by an overzealous Black cop who seems to be dehumanizing you just to showcase his fealty to the boys back at the district. That Black officers can perpetuate some of policing’s most virulent violence should be obvious to anyone who has watched the video of Black Memphis police officers mercilessly beating Tyre Nichols to death. It’s also obvious, I’m guessing, to Greg Love.

Love, who declined to comment for this story, has described the feeling of Montague’s bullet burning in his flesh in a way that still haunts me. He told Cleveland Scene in 2014 that his blood felt like it was boiling, like his whole body was expanding from the heat. As Love bled out in the front seat of his car, he wondered if this was the end of his life.

In his own way, a stunned Montague wondered the same thing.

III

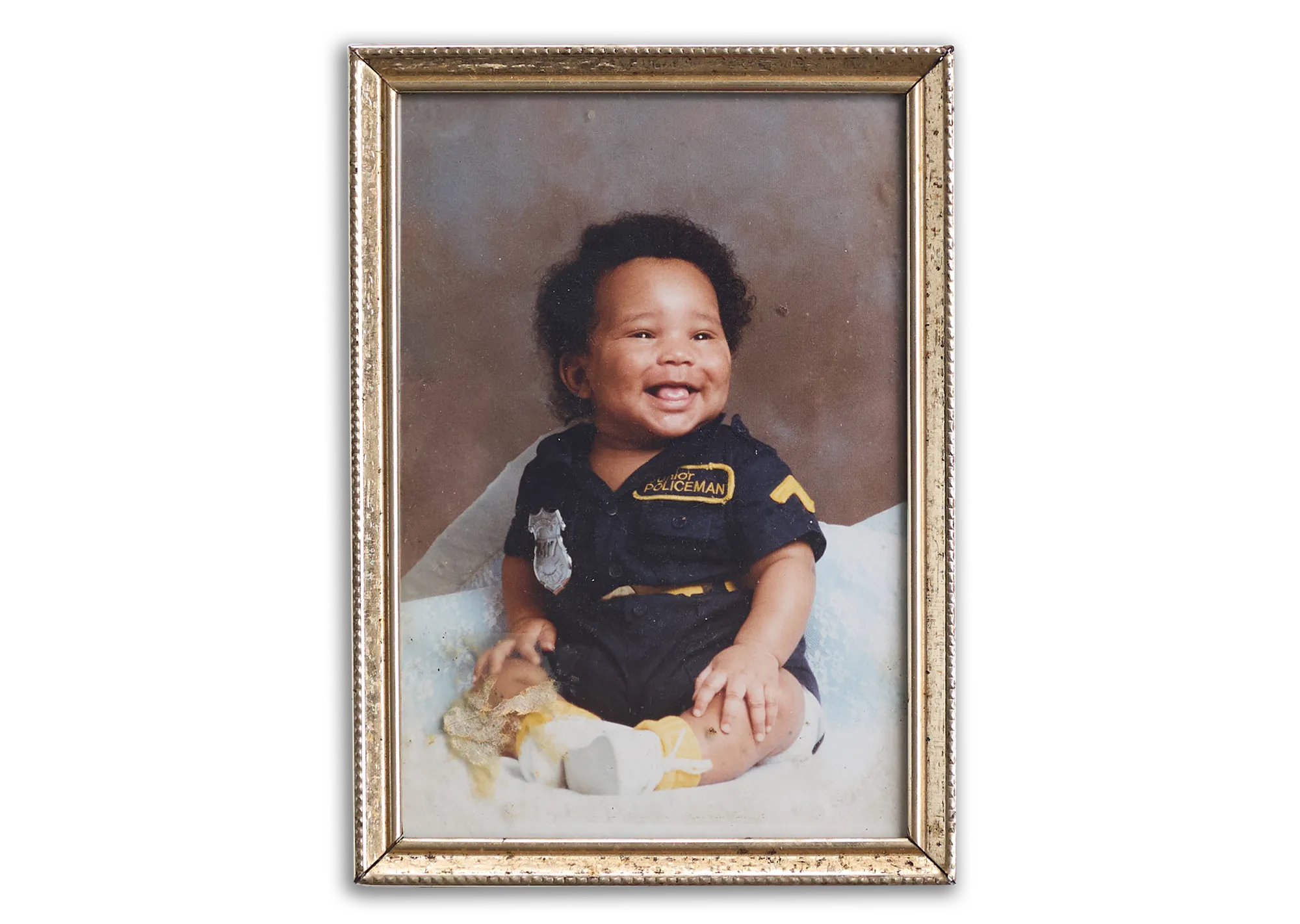

Montague didn’t grow up wanting to be a cop. Like many of us, he learned early on to fear police.

Once, as a teen, he couldn’t pay the parking fee of a downtown lot. Two officers stopped him and detained him alone while they searched his car for drugs and guns. They didn’t find anything, but the humiliation and shame of being suspected of serious criminality when he was only a boy left him shaken. Another time, driving home from his first semester at Tuskegee University in Alabama, he heard that sound you don’t want to hear when you’re trekking through the boonies. As Montague slowly steered his car to the shoulder of the dark Kentucky highway, his dad, awakened by the police siren, quickly coached him from the passenger seat. “Make sure to say, ‘Yes, sir,’ ‘No, sir,’” his father said. The officer let them drive away, but it was painful for Montague to see how the encounter instilled fear in his stoic Army veteran dad.

At Tuskegee, Montague majored in political science and aspired to law school. But after graduation, as his student loan payments came due, he took on odd jobs filling vending machines, working as a courier, driving a box truck. He briefly considered joining the military, but his veteran parents, all too familiar with the struggles of being Black in the armed forces, wanted him to hold out for something more in line with his education.

Eventually, Montague found a part-time job as a paralegal at a Cleveland law firm. He hoped the position would bring him one step closer to his goal of becoming an attorney. Instead, it introduced him to the person who would inspire him to become a cop.

Cleveland police officer Clark Kellogg made money on the side by helping the firm’s lawyers investigate and track down witnesses for their cases. Kellogg had been a star athlete in high school and college. And his son, Clark Jr., a first-round draft pick who played a few seasons in the NBA, was a local celebrity. To Montague, Kellogg was not just another relatable brother at the law firm, he was a role model. Montague explained to me that Kellogg attributed much of his familial and personal success to the stable foundation provided by his career in policing. He was living proof that a job in law enforcement provided a level of financial security that’s out of reach for many Black men in America.

This is the same sort of calculation my father made when he decided to take the civil service exam in 1981. Although my dad was always booksmart and raised in a tight-knit, conservative family, to survive on 117th and Union, he often had to front like he had nothing to lose. He ran with guys who were into petty crime that escalated after high school, in part because they lacked employment opportunities. As he saw members of his “gang” go to prison for botched robberies or end up in pine boxes, he realized that he wanted to take a different route. So he decided to join what he calls the “biggest and baddest gang,” the one that offered health insurance and a pension and helped keep you out of jail instead of barreling toward it.

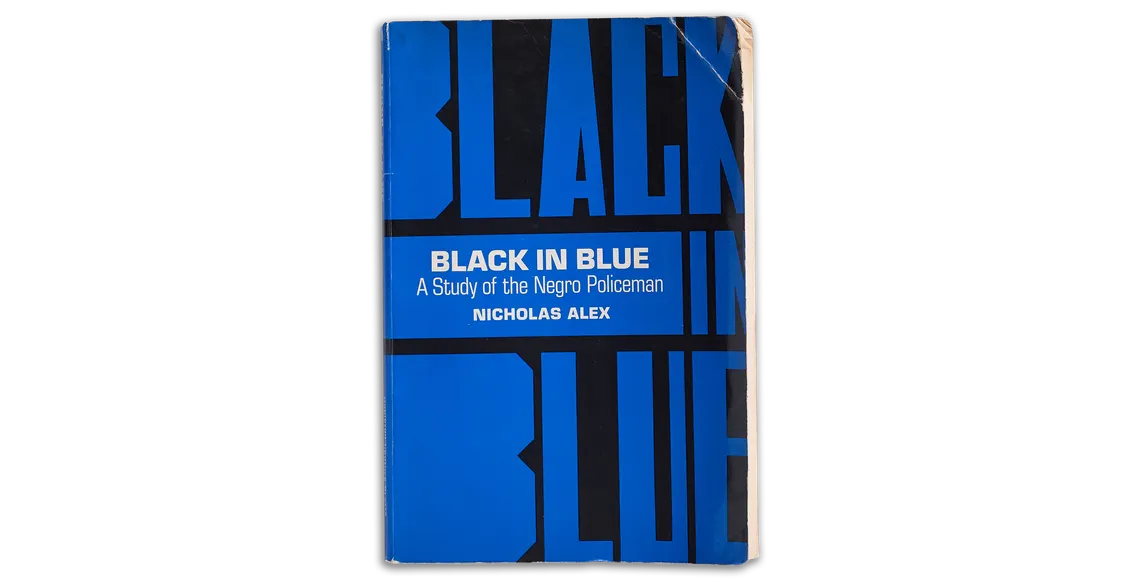

Sociologist Nicholas Alex, who in 1969 published “Black in Blue,” one of the first studies on “Negro policemen,” found most Black people in the profession were not drawn to it because they’d always wanted to be police officers. In fact, because police were widely seen as the “guardians of a society controlled by whites and used as a vehicle of pressure on the Negro population,” as Alex wrote, the profession was held in pretty low esteem in the Black community.

In part, policing’s disrepute with many Black people likely stems historically from its inextricable connection to the triangular slave trade. Precursors to policing were developed by European colonists as ways to protect their property and profit from the rebellious threat posed by the large populations of Africans that they enslaved. As sociologist Julian Go wrote in his book “Policing Empires,” “Cotton colonialism modalities of coercion — extending from the Caribbean to Ireland — provided the templates, tactics, operations, and organizational structures of the [civil] police.”

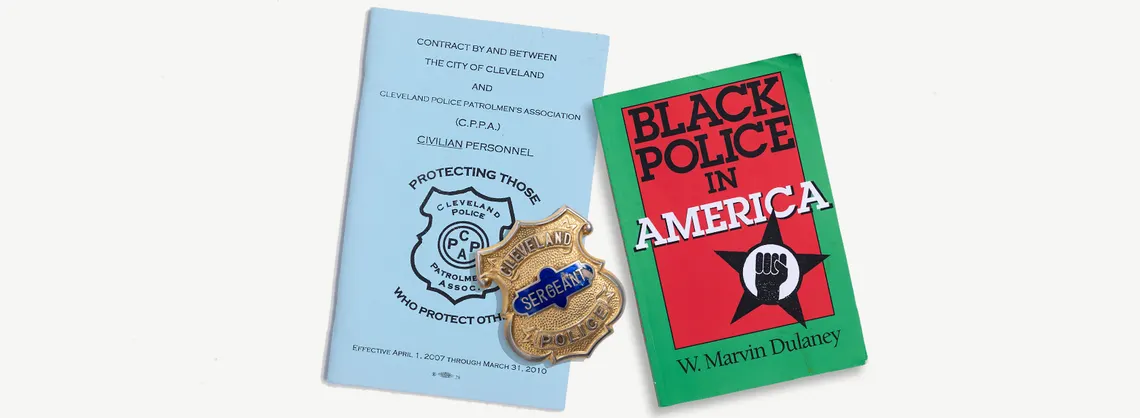

In slave societies like the antebellum American South, Black liberation was criminalized and the enforcers of racial oppression were nascent police. Because of this fact, historians believe the instances of Blacks serving in law enforcement in the United States before the Civil War to be exceedingly rare. The first known handful of Black people in policing in the U.S. worked in New Orleans in the early 1800s. And while they did things like patrol docks, according to historian W. Marvin Dulaney, the primary task of these mixed-race “free persons of color” was to help recapture their brothers and sisters who were fleeing to freedom. They did so, according to Dulaney in his 1996 book “Black Police in America,” in order to “improve their own precarious position in a society where skin color usually determined status and condition of servitude.”

While it remains an open question whether the presence of Black people in modern policing undermines the institution’s historic function of enforcing white supremacy, for decades, most White-dominated American police departments have used a multitude of methods to block Black people from joining their ranks.

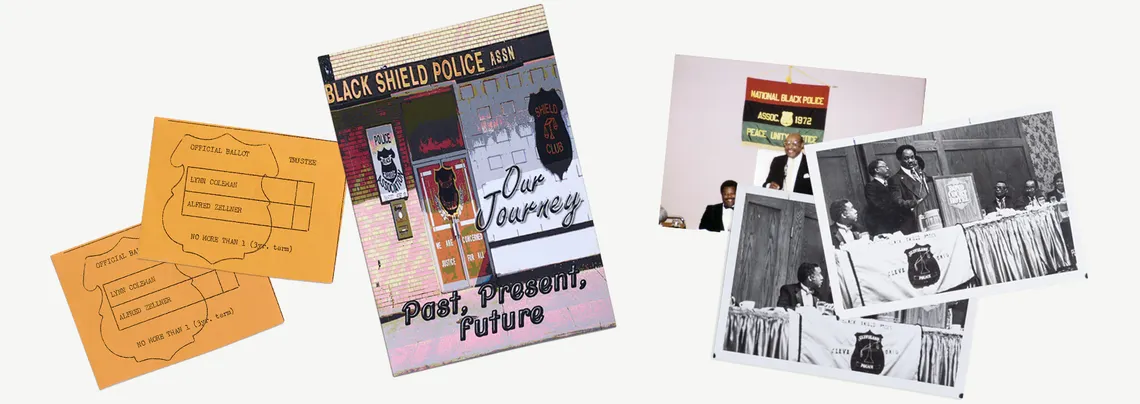

In the 1970s, Cleveland’s Black Shield, then known as the Shield Club, sued the city in federal court when these tactics took the form of culturally biased Civil Service tests, falsified or “lost” medical records and questionable lie detector and psychological exams administered by White cops with no specialized training or education. Back then, brothers were even disqualified for wearing Afros. Groups like the ACLU and the NAACP supported the Shield Club lawsuit because they believed that more Black cops would be better for Black people, especially in the aftermath of the tumultuous uprisings of the 1960s, which were often sparked by and stamped out with police violence.

While the lawsuit was still making its way through the courts, my own mother was purged from the eligibility list for the police academy after successfully passing the Civil Service test. Officials claimed she had moved out of Cleveland without notifying the city. But she owned her home and hadn’t gone anywhere. She told me that in order to get reinstated and join the academy, she had to go before the Civil Service Commission to prove her residency.

Ultimately, the Shield Club won its lawsuit, forcing the city to adopt affirmative action hiring practices, which dramatically changed the demographic makeup of the police department. Around that time, a number of Black police organizations across the country in cities such as Chicago, Atlanta, Yonkers and Memphis similarly pushed their departments to increase Black representation.

When the Shield Club filed its lawsuit in 1972, Cleveland was 38% Black, while its police department was only 8% Black. Thanks to the hiring, recruitment and promotion quotas imposed by the settlement, which lasted for more than two decades, the number of minorities in the police department climbed to nearly 40% by the mid-1990s, and the department hired a higher percentage of Black police officers than at any other time in its history. Two of those hires were my parents.

By the time Montague joined the academy in 2008, he told me, Black people were still subject to racialized bullying designed to push them out. Montague recalls one Black woman who passed the written exams but was struggling to complete a run that would fulfill her physical qualifications. She had one last chance, and if she didn’t make it, she would flunk. Before her final attempt, Montague remembers a White guy walking up to her and saying, “I hope you fail, because you are going to get someone killed out there.” Despite this, she managed to pass. Montague also remembers seeing a Black male gratuitously held in a painful position during a wrestling exercise until he started to cry in front of his classmates. That cadet didn’t graduate, he told me.

Perhaps Montague was able to navigate the racial tension in the academy because he’d spent much of his youth in spaces that felt unsafe for Black people. He was the rare Black boy doing laps on the swim team and blowing his trumpet in the band with White kids in the suburb where he grew up. To survive the police academy, he reminded himself, a college graduate and a lifelong athlete, “I deserve to be here.”

But what he would later realize was that the price for making it through the gantlet of the police academy was an indoctrination into White-dominated police culture. He vividly remembers a class where they analyzed the infamous beating of Rodney King by Los Angeles police officers. “They tried to teach you that he should have complied. That he was a big guy. That he was on drugs. And that the media tries to twist everything,” he recalled. “It’s like they were trying to brainwash you.” According to Montague, even his few Black instructors taught from a race-neutral standpoint that ignored the realities he knew about being policed as a Black person. “We had a Black instructor who came to talk to us about racial issues,” he said, “and pretty much told us racism doesn’t exist.” These lessons had an impact on Montague. “You start seeing things in a police perspective,” he said, “not like how you would if you were with your family.”

I’ve talked to many Black cops about this, about how becoming a police officer can change you, and make wrong things seem right and right things seem wrong. “A lot of Blacks came into the police department with good intentions,” said Alfred Zellner, who led the Shield Club in the 1960s. “When I came on, I thought if you have a White and a Black person working together, the Black officer is going to be able to keep things equal. But that didn’t happen. Guys would come on that way, but eventually they’d be just like the rest of them. The police culture, man, it grows on you.” According to a 2017 study, researchers found that Black cops tend to acquiesce to the norms of their departments in order to legitimize themselves to Whites in power, perpetuating even more aggressive uses of force than their White counterparts. The study found that it’s not until their numbers surpass 40% that their presence makes use of force less likely.

Montague says that in his early years as a cop, his family noticed how the job changed him. In 2014, when a New York City police officer killed Eric Garner using a prohibited chokehold after confronting him for selling loose cigarettes, Montague explained to his parents that Garner, an unarmed Black man, would still be alive if only he had complied, that the same thing would have happened if Garner had been White. By his own admission, despite the way he was raised, he’d become an All Lives Matter-type dude and a Blue Lives Matter-type cop.

Maybe it was this new perspective that made it easier for him to do things he would later regret. One of those moments followed the notorious 2012 Cleveland police killing of a Black couple, Timothy Russell and Malissa Williams, who died in a hail of 137 bullets after a 22-minute chase. That chase began when officers mistook the backfire of Russell’s 1979 Chevy Malibu for gunshots. Montague said that supervisors tasked him to spend hours on the night shift searching for shell casings, but he never found any. Russell and Williams were unarmed. “They wanted us to find something to support how that chase and shooting started,” he said to me recently. “But for me, I feel like they were trying to disprove what actually happened.”

But with his marriage and the birth of his children in the early 2010s, Montague’s chief concern was not asking questions about this system of policing, it was flourishing inside of it. “For me, at one point, I did everything it took to advance. I wanted to be a detective,” he said. “Well, how do you get into those special units? You have to impress. You make arrests. So now, that person you would have given a break for having an open container or having marijuana, you’re not. It’s all about status.” According to research conducted in New York City, this “broken windows” approach to policing does little to fight crime and can instead cause people to retreat from civic life and create even more cynicism around policing.

Also, to support his family, Montague began moonlighting. He worked as a part-time security guard protecting grocery stores from shoplifters. He also racked up lots of overtime pay by spending time in court testifying about the many tickets he wrote on patrol. “I wrote tickets to people that couldn’t afford ’em, knowing that they couldn't afford ’em,” he told me.

Montague, who a decade earlier could not have conceived of becoming a police officer, admits he had become what is known as a “traffic man” in police parlance. According to one of his former Black colleagues, Montague was the kind of cop who “tows people’s cars, writes up tickets, and just didn’t give a damn.”

IV

Greg Love was still in a hospital gown, his wounds and emotions raw after begging doctors to save his life. But there at his bedside, questioning him, was a Cleveland homicide detective.

Unlike some police departments across the country that have a siloed team of officials to investigate officers’ use of force, back in 2013, Cleveland’s Homicide Unit was tasked with the job. Documents from the Cleveland police investigation into the shooting show that at least in the beginning, the homicide unit named Love as a suspect because they believed he failed to comply with Montague’s orders. So in the hospital, he was photographed and sequestered from his loved ones. His cheeks were swabbed for DNA. And his hands were swabbed for gunpowder residue in search of evidence that he’d gone grabbing for Montague’s service weapon.

Montague gave his superiors a brief initial assessment immediately after the shooting, suggesting that Love tried to grab his gun, but he wasn’t asked to give an official statement or to submit to questioning for several weeks. He told me that he maintained his silence based on the advice of the Cleveland Police Patrolmen’s Association, the police union that represents rank-and-file officers. The union was notified as soon as the shooting took place, and the CPPA president hurried to the scene.

Although one would think that a cop would be forced to answer questions right after using deadly force, that was not routine in Cleveland in the 2010s. According to a 2015 deposition given by former internal affairs Lt. Bruce Cutlip in the proceedings of the lawsuit filed by Love, as long as the shooting was being evaluated as a potential crime by the homicide unit and the prosecutor, the department could not compel him to speak on it and potentially incriminate himself. This policy was in deference to Fifth Amendment rights of police officers. Although the prosecutor made the final judgment as to whether an officer in Montague’s position would be charged criminally, Cutlip explained that the prosecutor was greatly influenced by the recommendation of the police officers investigating a shooting. And investigators made these recommendations before they ever questioned the officer involved. In this lapse of time, Love’s lawyer, Nicholas A. DiCello, argued to me, officers could get wind of the evidence gathered against them and craft their story accordingly.

As the investigation into the Love shooting was underway, Montague was taken off the street and assigned to work in the police gym, which was customary. While he didn’t talk to detectives initially, he did have to tell his family, especially his father, because they share the same name, and he knew that name would be in the news for shooting another Black man. When he explained to his folks what happened, they became protective. He told me that they wanted him to quit and made clear they never wanted him working as a cop in the first place.

As accounts of the shooting spread in the media, and Montague began reading about the nascent Black Lives Matter movement, he started to grapple with his actions. He’d go over the scenario repeatedly with close friends, seeking reassurance over the way it all played out.

And being on the job among his White peers, he felt even stranger than before. Some wanted to bond over the bloodshed, he said. “I remember a White guy coming to me after the shooting and asking, ‘Why didn’t you kill him?’” Montague told me. He also felt alienated from the union that was supposed to support his interests, the CPPA, in part because of its origins.

Some historians tie the 1969 birth of the CPPA to Civil Rights-era Black uprisings and clashes with police who enforced the city’s de facto segregation. One of the union’s first demands from the city was a call for armored vehicles, “dumdum” bullets that expand in flesh, machine guns and grenade launchers. According to a 1969 Plain Dealer interview with a White police officer, White officers who didn’t sign up for the CPPA were accused of being “[n-word] lovers.”

But CPPA stalwarts like former President Steve Loomis say that the union began because the interests of patrolmen weren’t being represented by the Fraternal Order of Police, which was controlled by supervisors. “It was about getting away from the boss's union, because the boss is the guy that puts you up on charges, the boss is the guy that orders you to walk beats in the projects after a riot,” Loomis told me. “The CPPA formed because these guys had a right to be safe.”

But Montague didn’t feel safe with the CPPA or many of his police department colleagues. Instead, he found solace and community in the Black Shield. Although Montague had paid dues to the Black police organization, he had never attended a meeting. Yet almost immediately after he yelled “Shots fired” on that Saturday night in the Warehouse District, the Black Shield was by his side. But the Black Shield of 2013 was weaker and more timid than the one whose members had fought against private police in the 1940s to protect activists from violence or sued the Cleveland Police Department in the 1970s over its racist practices. Instead of being “malcontents,” as Cleveland Chief of Police Lloyd Garey called them in 1977, the Black Shield members had, for the most part, become quite content. So much so, the group allowed its hard-won racial hiring quotas to expire in 1995. And when the organization’s leadership spoke on police brutality in public, it was to tell the Black community that the violence “wasn’t racially motivated” and to discourage protest. The Black Shield even formed a political action committee with the CPPA.

This is part of a broader phenomenon legal scholar James Forman Jr. describes in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book “Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America.” “Although police work paid decently, it didn’t make the officers rich, and maintaining wages and benefits was a constant struggle. These realities would influence which battles black police — and their unions — took up in the 1980s and beyond,” he wrote. “Even those black officers inclined to use their political capital to fight police brutality would often find themselves in the minority. Most of their colleagues — black or white — wanted to fight for wages, benefits, and an equal shot at promotions.”

Black Shield headquarters, a former bank on the predominantly Black East Side, with its drop ceiling and well-worn wood paneling, quickly became a second home for Montague. This space is also where the Black Shield keeps extensive records, including meeting notes, newsletters, correspondence and photos that I have scoured to get a sense of the evolution of the group and its members. In 2013, after the Love shooting, Montague started spending countless hours there socializing with other brothers with tightly cropped Caesars and thinly lined mustaches. Soon, he was helping set up events like the holiday gift drive and annual dinner dances that raise money for scholarships.

It was helpful for Montague to talk to other Black men who’d shot and even killed people, and yet, stayed the course in their careers. Some of these men had walked that razor’s edge between their jobs as cops and their lives as Black men in America all the way to the Promised Land: a house in the suburbs, kids in college, a well-funded retirement.

“The Black Shield gave me the support that I didn’t get from Caucasian officers. They talk to you, they counsel you, they give you advice from their experiences,” Montague told me. “The Black Shield became my family.”

After Montague was cleared of criminal wrongdoing by the prosecutor based on the recommendation of Cleveland’s Homicide Unit, an internal affairs investigation into the shooting began. Almost one month after the incident, Montague was finally compelled by his employer to answer questions. He did so with a team of supporters: his lawyer, the CPPA and leaders of the Black Shield.

By January 2014, Cleveland Chief of Police Michael McGrath had issued his verdict. Montague was found to have violated department procedure — not for shooting Love, but for reaching inside the window of Love’s motor vehicle. Montague was sentenced to a three-day suspension. But he was only required to serve one day, with the other two days held in abeyance for the next two years. Not long after resolving the shooting, the city promoted Montague to sergeant.

There are some Black Clevelanders who see the paltry punishment Montague received as proof that cops have impunity when it comes to harming Black folks, because in their view, racialized state violence is inherent to policing, regardless of who is wearing the badge.

But Montague wanted the CPPA to challenge his punishment and take the city to arbitration. The union has done this routinely, including in controversial use-of-force cases that galvanize protests — the CPPA contested the firing of the officer who killed 12-year-old Tamir Rice, for example — as well as for innocuous internal issues that most citizens never hear about.

The CPPA didn’t choose that path in Montague’s case. “We fought for that kid,” said Loomis, who was head of the CPPA at the time. “We supported him all the way up until the point where he wanted us to file an arbitration. Given the circumstances of the case, a one-day suspension is a victory for him.” Current CPPA officials did not respond to requests for comment.

For his part, Montague saw his suspension and, perhaps most importantly, the CPPA’s decision not to challenge it, in entirely different terms. He saw it as racist.

Montague’s feeling of despondency only intensified in 2014 when a group of White officers involved in the 2012 chase and shooting of Timothy Russell and Malissa Williams sued the Cleveland Police Department for reverse racism. In their suit, they alleged that the department had a “history of treating non-African American officers involved in the shootings of African Americans substantially harsher than African American officers.” The suit pointed to Montague’s brief suspension as a key example.

Most of the research I’ve seen on the subject suggests that nationally, Black officers are disciplined more harshly in use-of-force cases than their White counterparts. According to an Indiana University study, Black officers were disciplined disproportionately more for misconduct in the police departments in three of the nation’s largest cities between 1991 and 2015. In Chicago, researchers found, Black cops were disciplined at a rate 105% higher than their White counterparts.

Ultimately, the Cleveland officers’ reverse racism lawsuit was thrown out. But the fact that it was filed at all cut Montague to the quick, especially after he believed he got second-class support from the CPPA. The betrayal he felt caused a racial reckoning in him that reframed the way he saw himself and his job.

When he can’t find the words to explain how these events changed him, Montague often calls upon the lyrics of a Jay-Z song called “The Story of O.J.” from 2017. In the chorus for the track, Jay-Z raps:

Light nigga, dark nigga, faux nigga, real nigga

Rich nigga, poor nigga, house nigga, field nigga

Still nigga, still nigga

V

The message on activist Kareem Henton’s T-shirt read: CLEVELAND POLICE MURDER BLACK PEOPLE. That’s what greeted Montague, the newly elected Black Shield president, at one of his first meetings of the Cleveland Community Police Commission in the spring of 2018.

After the shooting, Montague had quickly climbed the ranks of the Black Shield thanks in part to his devotion to the group, as well as the group’s desperation for new blood. Among Black officers in Cleveland, Montague was the face of change.

For Henton, however, Montague was more of the same. And the same was not good.

It was not lost on Henton that the commission itself, charged with civilian oversight of the Cleveland police, was founded in part because of Montague’s behavior on the job. His 2013 shooting of Greg Love helped prompt a Department of Justice investigation of the Cleveland Division of Police. Justice officials, who called the shooting an example of “poor tactics” and “unnecessary and unreasonable use of force,” concluded there was a pattern of misconduct and excessive use of force in the department and placed the agency under a consent decree. The Cleveland Community Police Commission was created to include community voices in the monitoring and reform of the department.

I first met Henton, a co-founder of Black Lives Matter Cleveland, at a protest he organized in January 2021. Standing at a microphone on a cold, rainy afternoon, he was flanked by the families of victims of police violence, including Samaria Rice. Rice’s 12-year-old son Tamir was shot dead by police in 2014 while playing with a toy pellet gun at a park on Cleveland's West Side. Facing the activist and the mothers was a crowd that included New Black Panther Party members in red berets, cargo pants and tactical armor toting machine guns, old White hippies passing out a communist newspaper called Revolution, and college kids tiptoeing around puddles in expensive sneakers. Before Henton led the crowd on a march to the Justice Center, where the city’s courts and jails are housed, he gave remarks likening police violence against Black folks to state-sanctioned genocide. It’s no wonder he felt a way about Montague joining the commission.

“I never gave him the time of day because I knew who the F he was,” Henton later told me. “I thought it was contradictory to have someone who was supposedly advocating for change in the system, when it was that same system that allowed him to get off scot-free. It is what helped him keep his job, maybe even kept him from going to jail.”

Montague told me that he saw Henton’s shirt as an opportunity. As the new president of the Black Shield, it was his job to build and maintain relationships with the Black community, even those who were outspoken and aggrieved. So anytime the men were in the same room, he’d try to start a conversation, forge a connection.

At one meeting, Montague approached him and said, “Just give me a minute.”

“And he just told me, quite honestly, ‘I know that everything that went down was wrong. It shouldn’t have happened, and I’m trying to make things right. I’m just seeking redemption,’” Henton recalled.

“And that touched me,” said Henton, who told me he first got involved in the drug trade while he was serving in the military. “I’m formerly incarcerated, been involved in the drug trade from the ’80s into the ’90s. I’ve got a very violent history. But I am not that person anymore. So for me to deny him an opportunity to redeem himself, for me to think that he’s being disingenuous would be highly hypocritical.”

Their relationship evolved from more cordial conversations to supporting each other on reform initiatives within the commission, to fostering a friendship. “It took a year of talking to where he started looking at me not just as a police officer, but as a man — a Black man,” Montague told me.

This friendship created a space where Montague could see himself and his actions from a new vantage point. He was finally able to stop “looking at what [Love] did wrong or could have done differently,” Montague said, and to start thinking about “what I could have done better … to not have shot him.” This empathy with a police shooting victim was something he realized was missing from his conversations at the Cleveland police department, and even at Black Shield headquarters. “Take the Tamir Rice incident, [the Black community] didn’t want the police to defend the actions of officers, they wanted us to say it’s horrific that a 12-year-old boy is dead,” Montague told me.

And it was this kind of empathy Montague began to express, not just in conversations with Henton, but publicly as the president of the Black Shield. When Montague took the helm of the organization in 2018, it didn’t take long for him to start evoking the group’s activist past by doing things that garnered support outside the department and condemnation within it. One of his first notable acts was to issue condolences from the Black Shield to Tamir Rice’s family, vowing to support the family and aid in the community’s process of healing.

Montague’s pledge to the Rice family was in direct conflict with the position of the Cleveland Police Patrolmen’s Association, which was waging a legal battle with the city to rehire Timothy Loehmann, the officer who shot Tamir Rice. It also came at a time when Tamir’s mother, Samaria Rice, was beginning to lean into her role as a fiery, outspoken advocate against police violence.

This public shift didn’t sit right with many officers who knew Montague’s past, former CPPA President Loomis told me. “At the end of the day, Vince Montague lost whatever credibility he had with us when he started with that race-baiting nonsense. It made no sense to us and diminished the voice of the Black Shield within the CPPA.”

Montague’s presidential predecessor and onetime mentor, Lynn Hampton, remembers how much Montague’s advocacy around race and policing was not only angering White cops, but also pissing off some Black Shield members. “There are certain statements that you got to be careful with,” Hampton told me.

For Hampton, a big part of being Black Shield president was balancing the public’s concerns with those of the membership. For example, when Hampton held the office in 2016, he was willing to repudiate the politics of Donald Trump when the CPPA, under Loomis’ leadership, endorsed the controversial candidate. But he would never have echoed activists and abolitionists like Montague did on that infamous Zoom call in the summer of 2020.

When I asked Hampton what he thought of how things worked out for Montague, he sounded as though his protégé’s ultimate fall from the force was foretold. “He ignited his own fire,” Hampton told me.

VI

In February 2021, I saw Montague hold up a shot glass filled to the brim with Fireball, the whisky that tastes like Big Red chewing gum and kills brain cells like turpentine. As I watched him chuck the honey-colored liquid headache to the back of his throat, a room full of cross-generational Black officers — some in their blues, others in street clothes — followed suit.

It was a notable night to drop in to the headquarters of Cleveland’s Black police organization. Earlier in the day, retired officer and longtime dues-paying member Erwin Eberhardt had “gone home.” His death, by way of a heart attack, was an unfortunate but readily accepted excuse for the retired and working members of the Black Shield to assemble. And so this was to be their first fête in some time — since before the plague of COVID-19 and social distancing and lockdowns and the murder of George Floyd. Montague made good use of the moment, floating around the darkened room in his billowing sweatsuit, a fitted cap and a pair of patent leather Air Jordans, shaking hands, giving hugs and laughing heartily.

You would never know — I certainly didn’t, anyway — that behind the scenes, he was under a tremendous amount of stress, as the life he’d built for himself around this organization, this job and the call to policing reform was slipping through his grasp.

The trouble for Montague started at the Duck Island Club, a bar on the ground floor of a three-story red-brick house that was built for poor immigrants in the late 1800s. During Prohibition, it was said to have been a speakeasy. In 2009, nightlife businessman Andrew Long turned it into an eclectic dive that would blast punk rock and play “Killer Klowns from Outer Space” on the TV behind the copper-topped bar. Its signature cocktail was the Irish Godfather, a boozy bev made of Jameson, amaretto and ice.

Montague first visited the Duck Island Club around Christmas in 2018 for a Black Shield toy drive. In addition to hosting, Long pledged a $250 donation. When Montague went to the bar a few days later to pick up the check, Long told him about troubles he said he was having with the police. When Long’s bartenders would call 911 about fights, he said, the cops would take forever to respond. And when they served alcohol after 2:30 a.m., the place would get busted by the vice squad.

Montague offered a solution: Hire Cleveland cops to do security.

Long declined to comment for this article. But in an interview he later gave to the Cleveland police, he said that Montague told him cops working security would not only keep the Duck Island Club safe, but they might bring their buddies in for late-night drinks, allowing him to stay open well into the wee hours without fear of the vice squad. While Montague admitted to me that Long did tell him about illegally hosting after hours in the past, he said his recommendation to hire police security was solely about making the bar safe.

Montague was the right person for Long to talk to about police security. By 2018, his security side hustle had become serious business. He’d done work for the Cleveland Cavaliers at the Rocket Mortgage FieldHouse. He’d organized security contracts for hot downtown Cleveland nightclubs. He would even go on to organize security for Black Lives Matter Cleveland as the organization faced threats for its activism. But the Duck Island Club was on Cleveland's West Side, which is considered the White side. “If I would’ve introduced Long to a Black guy, that guy might’ve got heat for being in a White officer’s territory,” Montague explained to me. “You don’t want to cause a war.”

Luckily, Montague knew just the right White cop. He called up Timothy Maffo-Judd, a police officer who had done part-time security for West Side hot spots such as ABC the Tavern and the Blind Pig. In January 2019, Montague helped set up a meeting between Maffo-Judd and Long at the Duck Island Club. Maffo-Judd later told detectives that during this meeting, Long expressed his desire to hire a “police officer to work at the social club in order to keep the vice unit from busting him after-hours.” While Long was being “very forward,” Maffo-Judd said that he was trying to catch eyes with Montague, giving him a “what the heck look,” but getting nothing back. Maffo-Judd, who declined to comment for this story, ultimately shot down the clandestine offer. And Montague later told me that as they walked out, Maffo-Judd turned to him and said, “I think this Long guy is FBI. I don’t trust him.”

It is not unheard of for the FBI to set up “sting” operations to uncover police corruption in Cleveland, but Montague felt Maffo-Judd was bugging. “I thought it was over the top,” Montague told me. “I didn’t know it was going to turn into a mess like this.”

After that meeting, Maffo-Judd insisted on reporting Long for attempting to bribe an officer and compelled Montague to do the same. Based on their reports to their superiors in the police department, Maffo-Judd organized his own sting operation with the Vice and Intelligence Units. Maffo-Judd’s covert operation had two parts: First, catch Long on tape setting up a bribery scheme. Then, actually work an after-hours shift and accept a bribe payment from Long.

I have an internal memorandum from the night Maffo-Judd worked security at the Duck Island Club, when the bar served alcohol until nearly 4 a.m. Reading it, both Maffo-Judd’s unease and the contempt the department had for the scene are palpable. The late-night patrons are described as “degenerates” and “homosexuals” who were “suspicious of law enforcement.” These night owls allegedly made “frequent attempts to lure Sgt. Judd into illicit conduct” by “directing him to the bathroom” and touching him “on his body.” After the night ended, Long paid Maffo-Judd $300. The evidence Maffo-Judd collected led to a vice raid of the Duck Island Club a week later, in which Long was arrested. One of the few items on his person was a Fraternal Order of Police courtesy card with Montague’s signature on the back.

Although Long pleaded guilty to charges of bribery, it took two years for his case to resolve. In text messages from 2020 obtained by the Cleveland police, Long suggested that the prosecutor was drawing things out with the hope that Long would serve up more info that would tie Montague to corruption. “He still believes I am holding out information on you,” Long wrote to Montague.

Long was a first-time offender, but in his sentencing hearing in 2021, Judge David T. Matia threw the book at him, alluding to “some talk of co-operation and proffer” with authorities that had not come to pass. Although Long told investigators that he was clear about his intentions to stay open after hours with Montague, he maintained that the only bribe he paid was a result of the sting set up by Maffo-Judd. The judge ordained that, “There will be no hope for judicial release” without cooperation, and sent off Long to serve a year in prison at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Judge Matia told me recently that because so much time has passed, he doesn't recollect all the specifics of the case. But he did remember that there was “some intimation made to [him] that Mr. Long could help with an investigation into unclean police officers.” Matia said, “Dirty police officers are a pretty bad thing for society, I think I made that pretty clear in the sentencing entry.”

The day before I visited Montague at the Black Shield in February 2021, watching him lead the celebration with jovial drinks and cigar smokes and dancing, he was called out by Cuyahoga County Prosecutor James Gutierrez for his relationship with Long, by then convicted of a felony. After looking at evidence collected by the Vice and Intelligence Units’ investigation into the Duck Island Club, which included text and social media correspondence between Montague and Long, Gutierrez cleared Montague of any criminal wrongdoing because, as he would later write, a “criminal case would be very difficult to prove.” But Gutierrez found Montague’s behavior so troubling that he took the rare step of writing a memo laying out his concerns to Cleveland police’s internal affairs unit — a first in his decades-long career, he said.

The Cuyahoga County Prosecutor’s Office declined to comment for this story. But when I reached Gutierrez, who is now retired, by phone recently, he said, “I wanted to make sure that Mr. Montague was handled like everybody else. Do I believe he was involved in a bribe scheme? Yes. But could I prove it? No.” His memo on Montague sparked an internal affairs investigation. And while Montague had been investigated before, after his shooting of Greg Love, this time things would end very differently.

The Cleveland Division of Police has a blemished reputation among many for its handling of officer misconduct. And Montague’s brief suspension in 2014 for shooting Love is one reason why. In 2020, a report by the Cleveland Police Monitoring Team tasked with overseeing the consent decree found that then-Public Safety Director Michael McGrath was “unreasonably lenient” in the discipline that he doled out and he and the chief of police “consistently failed to document any clear rationale for their decision-making.” I wasn’t able to reach McGrath for comment for this story.

McGrath’s successor was Karrie Howard, a former prosecutor. At first, Howard, a Black man, appeared far more amenable to community complaints over the shootings of Love, Tamir Rice and other Black residents. In his first year as safety director, Howard fired 13 officers for serious offenses including excessive force. But despite Howard’s seemingly tough approach to officer discipline, he quickly developed a contentious relationship with both the Black Shield and Black Lives Matter Cleveland.

During another visit to Black Shield headquarters in the winter of 2021, I listened in as Montague and his Black Shield peers chatted with the Vanguards, a group representing Black, Hispanic and female Cleveland firefighters. Under the bright fluorescent lights, they commiserated over what they saw as disproportionate discipline faced by people of color working Civil Service jobs, especially since the new safety director took office.

As an example, officers pointed me to the case of a Black female officer who received a 20-day suspension in 2021 for posting a satirical video pretending she was a dirty cop seeking a bribe. Meanwhile, around that same time a White male detective received a 10-day suspension for failing to investigate crimes assigned to him.

Montague’s plan to help fix these apparent discrepancies was to push the city council to change the city charter and formally incorporate the Black Shield and the Vanguards into the Division of Police’s disciplinary process. That plan was opposed by Public Safety Director Howard, who ended the Black Shield’s informal role as a monitor in disciplinary proceedings after he came into office.

But to some police reformers, focusing too much on the issue of discipline gets in the way of creating real change for the people being policed. As former Cleveland cop Charmin Leon put it, “I’m sitting in Black Shield meetings and people are talking about, ‘Yeah, I did do X, Y and Z, but then someone else did such and such, and they didn’t get [in trouble].’ Is this really the argument we’re having right now?” said Leon, who left the department in 2020 in frustration over barriers to reform. “This is why they laugh at y’all.”

In the summer of 2021, Montague was finally questioned by internal affairs detectives over his entanglement with Andrew Long. Armed with phone and text records, detectives were able to ask Montague specific questions about his correspondence with Long — questions they already knew the answers to, so they would know if he wasn’t being entirely truthful.

Detectives asked Montague if he told Long that he felt he was being targeted because he was Black. Montague told detectives he did feel that way, but he didn’t remember texting that to Long. But the detectives had the texts. “The city is now retaliating against me,” one message read. “It's crazy how a person’s complexion can cause people to do wrong to others.” That message was sent in May 2019, a few days after Long had been charged with bribery.

Montague’s internal affairs interview contained multiple exchanges like this that would form the basis of six charges of dishonesty, in violation of department rules. The fact that Montague maintained contact with Long after Long had been charged also garnered him nine charges of failure to “avoid the appearance of impropriety.”

Montague told me he knew staying in contact with Long wasn’t wise, but he felt bad for him. “They took everything from him,” Montague said. “And sent him to jail away from his family.”

Some activists believe that the real reason Montague was facing internal consequences at the department was not due to an improper association with Long but to his association with Black Lives Matter. Throughout 2021, Montague’s allies in Black Lives Matter Cleveland had been trying to bring accountability to policing in the city by taking power out of the hands of Public Safety Director Howard. Working with other groups, they’d collected more than 15,000 signatures for a ballot initiative in November that would give a Civilian Police Review Board the power to overrule discipline decisions by the safety director and would give the Community Police Commission that was established with the consent decree the final authority on all police discipline. The proposition was hotly opposed by Howard, who shared talking points with police commanders, aiming to undermine its public support.

Although it was police violence that had animated activists to champion the ballot initiative, BLM Cleveland’s Henton told me that the apparent discipline discrepancy between Black and White officers under Howard also helped highlight the impunity White cops seemed to enjoy. “We knew what we were dealing with, with this public safety director,” he said. “So how else were we going to get things done?”

Against Howard’s opposition, voters passed the ballot initiative in November 2021. Samaria Rice, along with several other mothers who lost their children to police violence in Cleveland, then published an op-ed calling for Howard’s firing, challenging his reputation on police accountability and claiming he had “betrayed his promises to the public.”

A few weeks after that, Howard fired Montague. Howard declined to comment for this article.

The magnitude of the difference between Montague’s punishment for failing to “avoid the appearance of impropriety” in 2021 and his lack of punishment for shooting a Black man in 2013 wasn’t lost on Henton, who published the following fiery statement:

“In a division where officers are routinely given slaps on the wrist or brief suspensions for everything from failing to investigate crimes to killing unarmed Black people, Montague’s swift firing seems exceptional, until you realize that, in the eyes of [Cleveland Police Chief Calvin] Williams and [Public Safety Director] Howard, he committed the gravest offense a police officer can do: speaking out against systemic racism and police violence.”

VII

On Jan. 7, 2023, Memphis police officers came to Tyre Nichols’ car door with their guns out. First they yanked the 29-year-old up out of his whip. Then they dropped him to the concrete, where he writhed from the shocks of their Taser and choked on their pepper spray.

He managed to get up and make a run for his momma’s house. Her home is where he would go every day to eat lunch on his breaks from working the second shift at a FedEx facility. He had her name, RowVaughn, tattooed on his arm. And he was about 100 yards away from her door when they caught him again. The cops took turns pummeling and stomping Nichols. As they tormented him, breaking his body, he cried out for his mother in vain. He died three days later.

In an essay for The New Yorker, Jelani Cobb wrote that the bludgeoning was “every bit as brutal as the one that led to the death of George Floyd.” The key difference was that this time the cops involved were Black.

When it comes to policing, Memphis and Cleveland aren’t too different. As in my hometown, the Memphis police force has a contentious history with the Black community, with memories marred by killings and harassment. The mid-South city also had its own hiring consent decree in the 1970s, which strong-armed the department into bringing on more Black cops in the hope that their presence would lead to reform. And those efforts appear to have made an impact, even if they didn’t reach their goal of fully representing the city’s demographics inside the department. According to the Memphis Police Department, in 2021, Black people made up 65% of the city population and 56% of police ranks. And yet, an increase in the number of Black officers didn’t help prevent a tragedy like what happened to Nichols.

Since the protests and outcry following the murder of George Floyd by former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, there’s been yet another wave of diversity recruitment and hiring in police departments across the country. While Black people made up about 11% of rank-and-file cops in 2020, they made up about 17% in 2022 and 14 percent last year. I wonder what sort of impact these shifts will have on our national problem of police violence.

When I asked Montague last year what he thought of the killing of Nichols and the fact that his killers were Black, like me and him, he spoke with a clarity one only gets from suffering.

“The police department is a gang,” he told me, referring to the way the culture envelops and changes you, whether you’re White or Black.

Samaria Rice believes that Montague, for a time, found a way to break that spell. “I think the death of my son has changed his life,” she said to me over the phone, emphasizing how different Montague was from just about any other cop she’d ever interacted with, not just in his sentiments, but in the ways he supported the movement with his police powers.

This sentiment was echoed by Charmin Leon, the former Cleveland cop who left the department after the summer of George Floyd protests to be a part of the Center for Policing Equity, a nonprofit that collects data to help departments implement reforms. For a time, Leon represented the Black Shield on Cleveland’s Police Commission. She was well aware of Montague’s shooting of Love, and yet, she says she had no question that he was genuinely trying to change the department to better the lives of Black people. She told me, “Sometimes the charges that we undertake have to do with a kind of reconciling in ourselves of our responsibility to the greater good, and sometimes it may be a point of redemption.”

But that path to redemption was cut off for Montague in Cleveland. Sensing that his firing was imminent in 2021, he started pursuing opportunities with other departments. But he says the fact that he was actively under investigation limited his ability to transfer to another department in northern Ohio. At the time, the Navy had a recruitment program for professionals like cops and doctors that offered them a rank and pay commensurate with their stature in civilian life. He’d come in as a petty officer first class, with benefits and pay over $80,000 that would ensure that he could uphold his family’s standard of living. Enlisting also would have, in theory, put a pause on the disciplinary process that was underway, because the department would typically be required to hold his job until he finished his service to his country. And so, to get “benefits to provide for my family and have options,” he turned to the military, the way his parents, activist Kareem Henton, and so many more had done before him — a decision born out of Black pragmatism as much as American patriotism.

In October 2021, Cleveland Public Safety Director Karrie Howard held his disciplinary meeting for the 17 charges Montague faced, just as Montague was being shipped out to Chicago for Military Entrance Processing. Chris McNeal, Montague’s lawyer and chief legal officer of the local Black Lives Matter chapter, sought to delay the proceedings, to no avail. And on Dec. 4, Montague’s wife was served his firing papers while he was down in Texas for technical training, learning military tactics alongside teenagers almost half his age.

Montague is now suing the city of Cleveland in federal court, alleging that he was unlawfully terminated from the police department while he was serving on active military duty. He also alleges that the city violated his constitutional rights when he was fired, due to the city's "pattern and practice of treating African-American police officers differently than white officers." Montague's suit calls for compensatory and punitive damages.

In court filings, the city denies Montague’s claims, arguing that he was terminated for being involved in a bribery scandal and then lying about it. The lawsuit is ongoing.

I contacted the city of Cleveland and the Division of Police to ask about the lawsuit as well as other topics discussed in this story. In an emailed statement, a police spokesperson said the department is unable to comment on active litigation. A city spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment.

Retired prosecutor James Gutierrez is not convinced by Montague’s claims that he was unfairly terminated.

“Everybody today looks through the racial lens, which at the end of the day, most of the time, has nothing to do with anything,” Gutierrez told me. “But Montague is with the Black Shield, so he's going to play that card. Oh, he’s so victimized! Well, his behavior during that case as a police officer was outrageous.”

“I have no idea about Mr. Montague’s social justice crusades,” Gutierrez said. “All I know is that his conduct deserved for him to be fired.”

Since Montague has left the department and the city, he’s been replaced by his former Black Shield Vice President Mister Jackson. Like Montague, Jackson is a leader with a complicated past. In 2015, according to the Plain Dealer, his girlfriend at the time claimed that he had attacked her at the house of another one of his girlfriends. She claimed he bit her chest and brandished a gun. He pleaded guilty to attempted assault, avoiding more serious charges, and kept his job. (Jackson spoke to me for this story, but did not respond to requests for comment about the incident with his ex-girlfriend.)

From the outside, it seems clear that Jackson has not picked up the mantle from Montague with regard to publicly advocating against misconduct, excessive force, or racism in the department or policing in general. “Nobody [from the Black Shield] has reached out to me about anything,” Samaria Rice lamented to me in September, when reflecting on the absence of the Black Shield in the struggle for police accountability since Montague was fired.

When I spoke with Jackson to get a feel for where he was leading the organization, he was understandably guarded. After all, the last guy who had the gig was fired. He talked slowly, choosing his words carefully, often seeming to strain for neutrality. He was clear, however, about the impact of Montague’s firing on the organization. “Vince made a lot of dynamic moves,” he told me. “After that, not only myself, but our members have become a lot more cautious.”

In the fallout of Montague’s firing, Jackson told me that the Black Shield has lost about half of its membership. While some of this decline is due to people retiring or leaving the department, it’s also a reflection of the group’s loss in credibility. “[The firing] put a serious stain on the organization as a whole, and it's taken a lot even now to clear that up to a huge degree,” he told me. This has forced the group to shift from more external concerns around broader police accountability to take on a more “defensive posture” of “protecting members” in internal department issues because, he said, “a lot of our responsibilities have been strained.”

According to Jackson, the group has given up on Montague’s initiative of trying to change the city charter by making the Black Shield a permanent monitor of the disciplinary review process in the Division of Police. The Black Shield has also pulled back its involvement with the Cleveland Community Police Commission, no longer maintaining a representative on the monitoring committee.

Samaria Rice sees all this backtracking as a shame.

Her cohort was successful in establishing the Civilian Police Review Board and has outlived one of their key opponents, Howard, who resigned from his position as safety director in February amid an internal investigation over a crashed city vehicle. But Rice and Henton both believe that the police reform movement in Cleveland is in a perilous place. For one, the implementation of the new Civilian Police Review Board has not lived up to their hopes. “Some of the people they brought on are puppets, and they’re serving the city well by derailing the process and going after things that they shouldn’t, focusing on things that they shouldn’t, and just not allowing progress to happen,” Henton told me in October.

In this contentious moment for police reform, Samaria Rice misses Montague. “Vincent was my connect,” she said. “And when it comes to police officers, to be honest with you, not too many of them are going to be like him.”

I met Master of Arms Montague at his barracks in the Joint Expeditionary Base in Little Creek, Virginia. Montague certainly looked like a new man. He’d ditched the standard police Caesar for a spiky gravity-defying high fade. And he’d marked his skin up for the first time with tattoos, perhaps to protect and gird himself in this new chapter — the shield of Shaka Zulu, a lion. He even got ink that symbolized the hard choices he believes he’s made for his family: an alpha wolf leading its familial pack.

“I think God answered my prayer,” Montague said to me in a way that felt like he wasn’t just trying to convince me, he was also trying to convince himself. “It’s just not how I imagined.”

I bet the barrack environs are a far cry from the home he shares with his wife and two sons in largely White and well-to-do Summit County, Ohio. Now, when he’s off duty, he returns to a sterile dorm room, not a place that appears as though he or anyone else living there is trying to make it a home.

There are few windows in the dim foyers, stairwells, hallways and private quarters. His sad bachelor’s quarters are sullen and dank. The floors are linoleum, the color of old bread, and the walls have that textured popcorn style not employed much since the 1980s. Against the overwhelming soullessness of the space, there are some traces of Montague. Some Head & Shoulders shampoo in the cramped shower. A pack of Fiji Water, his preferred brand, chilling in the wheezing white refrigerator. A rainbow of Air Jordan 1s lined up under his twin-sized bed. And an action figure of Marvel anti-hero Killmonger propped up proudly on the particleboard dresser. It’s an honorable totem Montague can project himself onto. After all, the movie character Killmonger found peace after giving his life to a cause he was so committed to.

But despite what Montague tells me, his ever-after seems strikingly familiar to days past. The work he does as a naval officer is not unlike what he was doing in 2013, when he shot Greg Love. Every day, he conducts patrols and traffic stops, with the main objective of preventing people from accessing areas where the Navy says they don’t belong. Except this time, when he gets off work, he’s about 500 miles away from his loved ones.

Although he’s probably more critical of policing now than ever, he’s wary of getting involved in any more movements of resistance or reform. That’s partly because he believes policing is intractable. “I don’t think that system’s ever going to change because there will always be a true majority in that system. And as long as they’re the majority, people are going to have to conform to them to survive,” he said. “I had a whole system fighting me … How was I going to win that war?”

He puts his energy now into providing for his family and protecting his Black boys with the money and security he earns from the Navy. But even though he’s largely given up his activist aspirations, everything that led him to take that stand still haunts him.

Sometimes he dreams that police officers are barging into his home where his kids and his wife rest their heads. Sometimes he dreams about shooting Love. “I can’t sleep at night because I am thinking someone’s going to hurt my family or my wife. So I’m up late watching the Ring door, making sure she’s good.”

He told me, “I watched White guys do stuff that was wrong. I watched a guy beat somebody up in handcuffs in the back of a police car, and I did nothing about it. I wrote tickets to people that couldn’t afford them, knowing that they couldn’t afford them … These are things that I was part of. These are things that I seen happen. And I did nothing. It is more than just the shooting. It’s all the stuff leading up to the shooting that’s on my conscience.

“And I can't make up for what I did.”