Subscribe to “Smoke Screen: Just Say You’re Sorry.”

In the summer of 2022, Larry Driskill received stunning news: The Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles had voted to release him on parole, and he would soon walk out of prison. But he wouldn’t be truly free. He remained officially convicted of the murder of Bobbie Sue Hill.

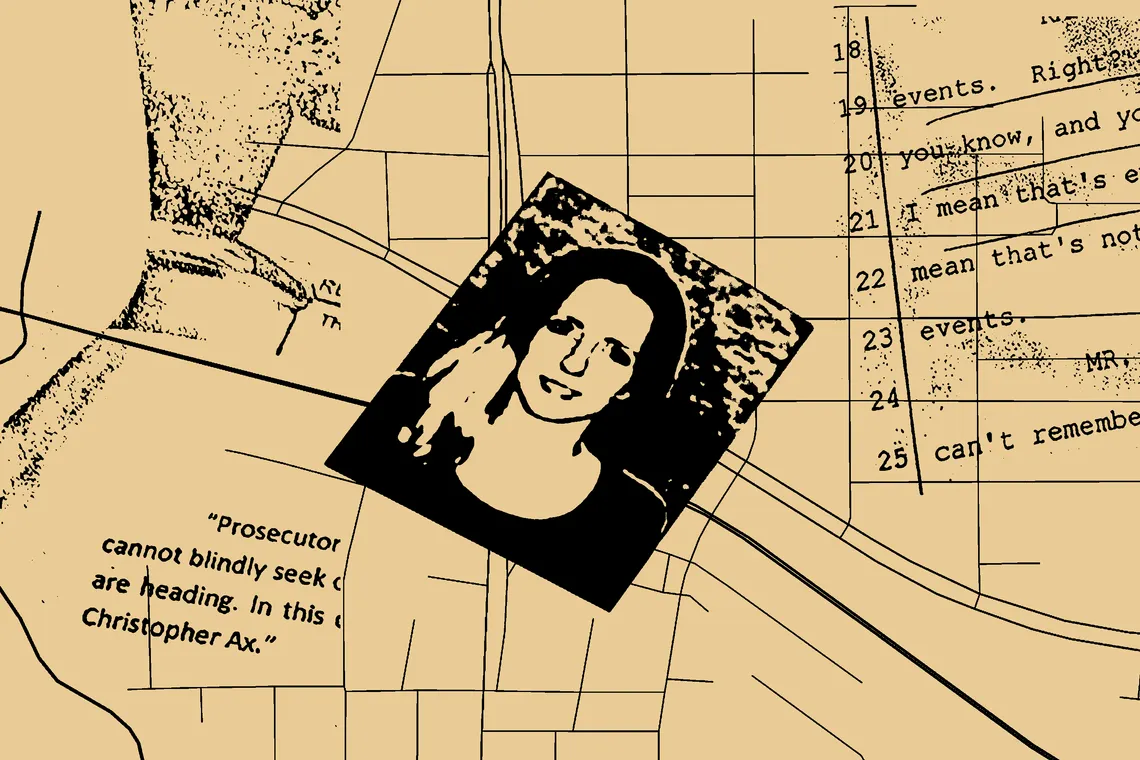

Lawyers at the Innocence Project of Texas are now seeking to overturn the conviction. If they succeed, Driskill’s name will be cleared, and he may be entitled to compensation from the state. Such an exoneration would tarnish the reputation of the Texas Rangers — and James Holland in particular — but it would also mean that the victim’s family would return to not knowing who killed her, or whether that person is still at large.

At the same time, Driskill’s outcome may contribute to a larger reckoning in how detectives and prosecutors handle cold cases. Already, legislators in several states have voted to bar police from lying during interrogations when a suspect is under 18 years old. Other states have begun considering bills that would ban lying to all suspects, not just children.

Texas lawmakers have not yet considered such bills, but in 2023 they did vote to ban testimony from witnesses following forensic hypnosis, which was a key element in the Driskill case. It is now up to Texas Gov. Greg Abbott to decide whether to sign the bill.

“Closure Doesn’t Exist,” the sixth and final episode of “Smoke Screen: Just Say You’re Sorry,” looks for larger meanings in the case of Larry Driskill, considering the circumstances of Bobbie Sue Hill’s family and the current state of cold case investigations. We speak with Christy Sheppard, who lost a loved one to murder and later learned the authorities had imprisoned the wrong people for the crime. And we meet Mindy Montford, a senior Texas prosecutor focused on cold cases, who explains why police may continue to fight for controversial techniques in the interrogation room.

Go deeper:

-

District Attorney Jeff Swain’s full emailed response to questions about the Larry Driskill case

-

More on Texas prosecutor Mindy Montford’s work on cold cases

Transcript:

Before we start, a warning that this episode contains descriptions of violence. Please take care as you listen.

Coming up this time on “Just Say You’re Sorry”:

Mindy Montford, Senior Counsel, Cold Case and Missing Persons Unit, Texas Attorney General: I'm not saying it doesn't happen where there's a false confession because they were tricked. You've seen that. But to take that tool away from law enforcement? I have a hard time with that.

Christy Sheppard, cousin of Debbie Sue Carter, who was murdered in 1982: When most kids are learning, maybe, that the boogeyman isn't real, I learned that he very much was.

Larry Driskill: I know time that I've lost, I can't make up. There's nothing I can ever do to get that time back.

Larry Driskill: Guys can get mad over the weirdest things in here.

Larry Driskill has a job working in the kitchen at his prison. He’s part of a massive operation, feeding hundreds of men.

Larry Driskill: We have 280 to 290 people who come in to eat the food. [Some people] can't have salt in it. Certain people can't have peanut butter. They’ve got to have cheese sandwiches. And then we help on the regular cook floor sometimes too.

He’s been incarcerated for seven years by now, and this is his life: work, sleep, checking in with his lawyers — usually with snail mail letters that he writes by hand. Sometimes his mom, Lynda, comes to visit.

As an older guy, he can mostly avoid trouble. But not today. He’s on a break from kitchen work.

Larry Driskill: A guy got mad cause we didn't put enough ice in the coolers.

This other prisoner gets some water and takes a sip. It isn’t cold enough. He snaps.

Larry Driskill: I was watching TV and he sucker-punched me.

Driskill told me he tried to stay calm, and to not rat this other guy out to the authorities.

Larry Driskill: I told them I slipped and fell, because I don't want get myself in trouble. What am I gonna do? Fight him? I was under review for parole.

A fight is the last thing Driskill needs right now. His case is about to come up for review by the parole board.

At the same time, The Innocence Project of Texas is planning legal action for him, to overturn his conviction. But that could take years — and might not work at all.

So parole is the only other way he can get out of prison before 2030. He meets with a lawyer who specializes in these kinds of applications.

Larry Driskill: He said, “We're a little late to the game, but we got this.”

Driskill’s team only has a few weeks to prepare for the hearing. When the day of that hearing rolls around, July 15th, 2022, his mom and stepdad are allowed to watch the lawyers make their arguments over Zoom.

Larry Driskill: So mama and my stepdad could sit there and listen, and they could even put some input in.

But Driskill isn’t allowed to be there. So it goes without saying that I wasn’t either. What went down in that hearing is all confidential by law, so I don’t know what happened. The parole lawyers might have presented my own reporting on the case, maybe. It’s also possible that the prosecutors, the sheriff’s office, or, heck, even James Holland may have submitted arguments.

I also don’t know if Bobbie Sue Hill’s family wrote a letter or made an appearance, saying that he should stay in prison. Sometimes victims’ families do that.

After the parole board hearing ends, there’s a long wait. Every day, Larry’s mom, Lynda, pulls up the website of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. She types his name in to see if there’s any update on his status.

It’s the world’s most bureaucratic website, with the most personal, earth-shattering information: Will your loved one stay in prison, or come home?

Anyone can visit this website, so I’m checking as well. So is Jessi Freud, Driskill’s Innocence Project [of Texas] lawyer who we heard from in the last episode. I call her sometimes, and I text Driskill’s mom. But everyone is just stuck, waiting.

Larry Driskill: I was always checking with the reentry guy, on Tuesday, when I went to V.A. meeting, and when I went to Catholic church, on Thursday, I'm checking with the parole lady: “Hey, when are we getting a date?” or whatever. I was beginning to wonder whether I was ever gonna get a date. I thought, ‘At this rate, I don’t know.’

So then, one evening, Driskill is walking through the corridors of the prison. He decides to make his daily phone call to his mom. He walks over to the phone and starts pressing buttons. The whole process is slow, agonizing really.

Larry Driskill: You have to [press] one if you want them to pay for it, two if you're paying for it out of your own funds, and then you put in your [Texas Department of Criminal Justice] number.

Then I just have to tell ‘em “Larry Driskill.” Then after you do that … and you hit the pound sign … once it does that, it rings.

Around that time, I’m in Manhattan, when I get a call from Jessi Freud.

Jessi Freud: How are you?

Maurice: I'm good. I'm at a seminar in New York.

We’d been playing phone tag. She’d been at a salon getting her hair done.

Jessi Freud: Yeah, of course. Not very professional. I was getting my weave moved up, so you were fine. This was good timing. I just finished.

Maurice: Oh, OK. Great.

Jessi Freud: So there's really good news.

Maurice: OK.

And then, at this precise moment, my phone cuts out.

Jessi Freud: Larry made parole. Can you hear me?

Maurice: Sorry, there was a cutout for a second. Sorry.

Jessi Freud: Larry made parole!

Maurice: What happened?

Somehow, Driskill has beaten the odds, and is going to be freed after seven years behind bars. He’s going home. But he remains convicted of the murder of Bobbie Sue Hill. And so there will still be severe restrictions on his freedom — think ankle monitor, strict schedules, limits on travel.

As he waits to be released, he knows he’ll still have that dark cloud hanging over him on the outside. What he wants is to be declared innocent.

From Somethin' Else, Sony Music Entertainment and The Marshall Project, this is “Smoke Screen: Just Say You’re Sorry,” Episode 6: “Closure Doesn’t Exist.”

So it’s the summer of 2022, and Larry Driskill is looking forward to being released from prison. His lawyers are thrilled. Jessi, especially, sounds like she’s walking on air. I hear there’s going to be a small crowd outside the prison to greet him and I’m making plans to try to be there too. I want to talk to him without a prison guard breathing down our necks, checking the clock, so I can ask him honestly about his feelings towards James Holland and the way his case was handled.

But I also find myself wondering, ‘What does Holland make of this? The fact that the guy that he put away for the murder of Bobbie Sue Hill is out after only seven years?’

When Driskill made parole, I thought maybe I’d hear from Holland. Maybe he’d give an interview. But nothing. I learned that he was retiring from the Texas Rangers. He’s still young, in his early 50s. I have a Google alert set up for him, and he pops up on an episode of “48 Hours.” He’s a talking head, analyzing a murder case that it doesn’t seem he actually worked on. I’d love to hear his perspective on this case, on these interrogation tapes that we’ve been poring over all this time.

As you may remember from the last episode, I did receive an email from the Parker County district attorney, Jeff Swain. He oversaw Larry Driskill’s prosecution, and he wrote me a long message praising Holland’s skill. Basically, Jeff says, ‘Holland’s tactics are effective.’ Obviously. Nobody knows that better than Larry Driskill.

But we also know that these tactics come with risks of producing false confessions. So how do police justify their continued use? Because Holland won’t answer these questions himself, I found someone else who knows exactly the kind of pressure these investigators are under, when working cold cases.

Mindy Montford: I cannot stand the fact that somebody got away with such an injustice and they're sitting there thinking, you know, ‘I got away with it.’ Just drives me.

Mindy Montford is senior counsel of the statewide Cold Case and Missing Persons Unit in Texas. This is a huge job.

Mindy Montford: There's over 20,000 unsolved homicides in the state of Texas.

Mindy made a point of not looking at our particular case, Larry Driskill’s, as she’s not able to comment on his situation or the work of other prosecutors. But she’s fine with me asking her about some of Holland’s tactics in general terms, starting with lying to suspects in the interrogation room.

Maurice: You know, there's a growing movement of sort of innocence project-type lawyers who say that should be banned entirely. You have cops who say, “We need that as a tactic. These guys are lying to us, so we need to lie back to them.” How do you think about lying?

Mindy Montford: I have seen that tactic work in a lot of confessions where I believe the person confessed legitimately. We had corroboration, and they were ultimately convicted, and I believe that was a righteous conviction. I'm not saying it doesn't happen where there's false confessions, because they were tricked. You've seen that. But to take that tool away from law enforcement? I have a hard time with that.

The problem is, every time an innocence project says, “Larry Driskill is innocent and Holland’s lies put him in prison,” someone like Mindy Montford can say, “Well, lies put this other guilty person in prison.”

I also ask Mindy about hypotheticals, when an interrogator says things like, “How, hypothetically, might you have committed this crime? Try to imagine it.” Does she see any risks there?

Mindy Montford: I think you've got to look at the mental faculties of the individual being interviewed: the age, the background and circumstances and whether this person was more susceptible to some of this stuff than somebody else who wouldn't be. And again, that's why I wouldn't take away that tool from law enforcement, because you may absolutely need it to solve a very heinous triple homicide…

Maurice: Mm-hmm.

Mindy Montford: …but it may not be the best technique to do with somebody who is more susceptible to that. And I think as an investigator, you need to think about that because how is this going to look, ultimately, to a jury? They are not going to like it if you are beating up on this young kid who can barely read and write. They're just not gonna like that.

Which got me thinking: How would a jury have reacted to Driskill’s confession? Would they have convicted him? Or would they have seen Holland’s interrogation as coercion?

Mindy Montford: I think that's incredibly important. Watching juries over time, their opinions have changed about confessions. It used to be, “Yup, that person confessed, they did it.” I think now they do demand and require more than just that, and they don't necessarily just take a confession at face value. A confession is meaningless if you don't have corroboration for that confession.

I take Mindy’s point that juries have a more sophisticated understanding of evidence and confessions than they used to, but there’s a larger issue here: We both know that usually there is no jury. In nine out of 10 cases, including Larry Driskill’s, the defendant takes a plea deal.

Maurice: What would you say in the case of somebody who takes a plea deal and it never even goes to a jury, that it's sort of ‘on them’ or…?

Mindy Montford: Well, that brings up a whole other issue with your [legal] representation. And you want somebody who can be able to say, “Look, if you go to trial, here's what you're facing. X, Y, and Z. If you take the plea, these are the benefits, these are the cons.” And that's where a good lawyer comes into play.

Mindy’s answers here boil down to: There are other parts of the justice system that can be a check on interrogators who go too far. The solution isn’t to ban lying, or hypothetical questions, or all those other tactics which maybe aren’t even practical to ban.

The solution is better public defenders, pushing back after a detective gets tunnel vision and goes too far and arrests an innocent person. In the better system she’s imagining, those public defenders don’t push their clients to take plea deals. They take those cases to trial. And then these intelligent jurors, people like you and me, can dissect the interrogations, and decide fairly whether a confession is legitimate.

Which, sure, I can imagine that world. But for decades, defense lawyers have struggled to get enough money to do their jobs properly, to not just push their clients to give up and go to prison. In this context, there will always be a risk that innocent people will be swept into the prosecution machine. But how much risk are we as a society willing to accept? How many guilty people in prison are worth one innocent person?

Mindy used to be a defense lawyer herself, and she’s definitely concerned about the rights of defendants. But now as a cold case prosecutor, she's more connected to the people who are the most desperate for a conviction: The families of the victims.

Mindy Montford: They have such resilience, and it's amazing that, this many years later, they're still invested, as if it was yesterday. And they're just so appreciative to have somebody who's not giving up on their case either…I think they just want to know the case has not been forgotten and that somebody is looking at it.

Fewer murders are getting solved these days than in the past. Resources are scarce. More cases are going cold. And listening to Mindy, I can imagine just how incredible it must feel to tell a family, “We got the person who killed your loved one.”

What lengths would you go to get that feeling, especially if the tactics were legal? Again, Mindy is certainly not speaking for James Holland, but you can get a sense of the well he can draw from, the righteous motivation that would keep you hour after hour in that interrogation room.

And if we’re honest, one of the reasons we celebrate detectives like Holland — in real life, and in movies — is that they’re willing to do what’s necessary to get the bad guy.

The journalist Jillian Lauren, who got to know Holland through the Sam Little case, compared him to a kind of comic-book vigilante.

Jillian Lauren: I think that we demanded Jim Holland in the same way that we demand Spider-Man. He gets shit done, and he comes in like a superhero.

I mean, try to put yourself in the shoes of Bobbie Sue Hill’s family for a moment. Would you really question Holland’s methods if you felt like he caught the guilty person and brought justice to your loved one?

So in light of everything we know now, how does Bobbie Sue Hill’s family feel about Driskill’s efforts to clear his name? As I mentioned before, none of her family wanted to speak on tape. But after Driskill was approved for parole, I talked again to two of Bobbie Sue Hill’s aunts. They were both upset about his release. They still believe Holland got the right man.

Before I reached out to them, I had asked for advice from an organization called Healing Justice. They work with families in a similar situation to Bobbie Sue Hill’s, where a murder might be linked to a wrongful conviction.

Healing Justice told me that lots of victim[‘s] families in these cases don’t want to talk to the media, especially while the legal process is still playing out. And there are good reasons for that.

But they did say, “We know other families in a similar situation, who do want to talk publicly. We can introduce you.” And this leads me to a conversation with Christy Sheppard. Hearing her story will help us understand what Bobbie Sue Hill’s family and friends are having to confront in the Larry Driskill case.

Christy’s cousin Debbie Carter was murdered in 1982. The case became famous as the subject of a book by John Grisham, as well as a Netflix documentary. They’re both called “The Innocent Man.”

But of course, as the title implies, the spotlight was on a guy who went to prison and his legal case, not the family left behind.

Christy Sheppard: My cousin Debbie was 21 years old when she was murdered in my small hometown.

One night, in 1982, Debbie Carter left her waitressing job at a bar in Ada, Oklahoma. The next day, she was found dead in her apartment. At the time, her cousin Christy Sheppard was 8 years old.

Christy Sheppard: She lived actually down the street from my mom and I.

And they were close. Christie admired Debbie, almost like a big sister. Her death had a volcanic, devastating effect on Christy and those around her, which lasted decades.

Christy Sheppard: You know, like I said, I was 8. So when most kids are learning maybe that the boogeyman isn't real, I learned that he very much was, that there are things that come into your house in the middle of the night and take everything and that there is nothing that you could do.

But as Christy grew up, and years passed, there were still no arrests.

Christy Sheppard: And we just kind of floundered there for about five years, knowing who it was. Knowing who we thought that it was.

In 1987, when she was a teenager, prosecutors finally charged two men, Ron Williamson and Dennis Fritz. They were known to drink at the bar where Debbie Carter worked. At their trial, the prosecution had a compelling case. Apparently Debbie had told a friend that these guys “made her nervous.”

And then a bunch of individual hairs from the murder scene, the prosecutors said, matched the two men. Police also had a statement from one of them, Williamson, describing a dream in which he killed Debbie Carter, and he gave sickening descriptions. The prosecutors said, ‘This is basically a confession.’

Ron Williamson was sentenced to death. Dennis Fritz went to prison for life.

Christy Sheppard: We thought we knew exactly what happened. It seemed pretty evident and cut-and-dry. That was all there was to know about the case. I think it was 12 years later that articles began to come out in the newspaper, that they were gonna do DNA testing on some of the biological evidence.

All this time later, further DNA testing revealed that those hairs from the crime scene didn’t actually match Fritz or Williamson.

The rest of the evidence unraveled too, and they were ultimately exonerated and released in April of 1999. Williamson had, at one point, come within five days of execution. The two had been wrongfully incarcerated, respectively, for 12 years.

Christy was 25 years old when they got out.

Christy Sheppard: We watched them walk out of the courtroom like nothing happened.

Maurice: What was your feeling towards Williamson and Fritz?

Christy Sheppard: Really kind of disgusted. I mean, we didn't understand how you could be so certain that it was these two men. How does that just all go away? And we just figured that it was some kind of craziness. We really just didn't even understand, to the point that the day that they were exonerated, I went to go eat dinner with my family, and we’re sitting at a table and then Williamson and Fritz and their entire [Oklahoma] Justice League [organization] comes in and sits at the table behind us.

Maurice: My God.

Christy Sheppard: And of course they don't know who we are.

Maurice: Yeah.

Christy Sheppard: But I was sitting at the end of the table with my back to them, and all of a sudden, I noticed one of my cousins, and my dad start to kind of look around and everybody kind of froze. And then I turn around and see who is sitting behind us. And we paid for our drinks and left. We didn't even stay. We didn't know what to do.

Not only had Williamson and Fritz been exonerated, the DNA matched a man named Glen Gore. He had gone to school with Debbie and was a state witness at one of the original trials.

Christy Sheppard: I think he was on the run for about 10 days. Then a couple more years [later], he was charged, and a couple more years after that, we went to trial again.

Gore was convicted in 2003, and then it was overturned on appeal because of issues in his trial — meaning more uncertainty for Christy’s family — and then, in 2006, he was sentenced to life without parole. He remains in prison.

Christy Sheppard: I mean, thinking back, and reading through it now, I'm just floored. And that's where you really begin to see how all of these things, from the confession, to everything else, was just made up. None of it was real.

Christy told me that one of the things that especially hurt her and her family was how Debbie slowly disappeared from the official story — the way the case was talked about in the courtroom, and in the media.

Christy Sheppard: Initially, it was the Debbie Carter case. Everything had to do with her. Once they had those arrests, it became the Ron Williamson and the Dennis Fritz case. And there were times that she was only referred to as a bartender, and they didn't even mention her name.

In the media, the main characters of the story were these two innocent men freed from prison. When they got out, it was like, ‘That’s it. There’s your happy ending.’

Christy Sheppard: I think I looked one time and there were several years of articles — there was a gap of several years that her name wasn't even mentioned, and there was no picture of her, but there was always a picture of them. In cases like this, the victim just gets reduced to another piece of evidence.

Maurice: I mean, to that end, does that lead you to specific ideas about how the media can do better in this regard?

Christy Sheppard: I know it's scary to reach out to victims and surviving family members. But I think we at least need to try and not make the assumption that we don't want to re-traumatize them, or we don't want to stir anything up because they need closure. Well, that's probably one of the biggest misconceptions about any of this. There is never closure. That doesn't exist.

As Christy spoke, I was thinking about Bobbie Sue Hill, the way some early articles about the Larry Driskill case emphasised how she did sex work. I knew from the family members I talked to that they were really unhappy with that being so front and center in the official story about her and her death. It’s unavoidable to some extent, given the circumstances of her abduction, but obviously there’s so much more to know about her.

Did we treat her memory and her family’s experience in the most ethical and considerate way? I hope so. Ultimately, it’s for them to decide.

In the end, the conversation with Christy led me to a simple but upsetting idea: If Larry Driskill’s team does one day convince a court to clear his name, it may tarnish the reputation of James Holland, and present a public relations problem for the Texas Rangers. I will move on. The Innocence Project of Texas will move on.

But Bobbie Sue Hill’s family will return to not knowing who killed her, or whether that person, whoever they may be, is still out there.

I should say at this point that if you do relate to any of the experiences Christy talked about, you can reach out to Healing Justice at healingjusticeproject.org.

After the break, we’re switching perspectives again, as I make the journey to meet Larry Driskill for the first time as a free man. And he wrestles with the damage that’s been done to his life.

Larry Driskill: I trusted the law, and I won't do that anymore.

Maurice: Are you saying you feel like Holland betrayed your trust?

Larry Driskill: Yeah. I feel like he threw me under the bus and backed over me a few times.

[AD BREAK]

Maurice: We are speeding down the road to get to the prison, to the Boyd Unit where Larry Driskill is about to be released. We got up at, like, 5:00 a.m. to make this drive from Austin.

Here I am again, driving to another Texas prison, in the middle of nowhere, about an hour east of Waco. I’m actually turning off the highway just past the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame.

Driskill’s mom, Lynda, his lawyers, everyone is nervous. What if he gets blamed for a fight? What if the bureaucracy finds some other reason to cancel his release? The general feeling is, ‘Until he’s actually out, anything can happen.’

So there's this sort of buzz in the air when I arrive.

Maurice outside prison: How you doing? Good?

We’re maybe 50 yards from the prison entrance. We’re not allowed any closer. [Driskill’s lawyer] Mike Ware introduces me to Driskill’s mom, Lynda, and his stepdad.

Maurice: Nice to meet you. Are you Lynda?

Lynda: Yes.

Maurice: Oh, we haven't met yet. It's really nice to meet you.

Driskill’s stepfather: She's the one that produced him.

They eventually walk closer to the prison entrance itself, which is surrounded by barbed wire. The rest of us make small talk. Ashley Fletcher, who first grew passionate about the case as a student, and now actually has her law degree — she’s here too.

Ashley Fletcher: I'm Ashley.

Maurice: Oh, you're Ashley.

Ashley Fletcher: Yeah. We've spoken on the phone.

Maurice: We have spoken. Totally great to meet you in person.

Ashley Fletcher: Nice to meet you in person too.

Hours pass. Nobody really knows why it’s taking so long. The sun is getting higher, it’s hot. And then around 10 a.m., we see in the distance a couple of figures making their way out towards Driskill’s mom’s car. It dawns on us all. This is the moment Larry Driskill steps outside the prison walls for the first time in seven years.

Maurice: What's happening?

Mike Ware: He gave us a go-time sign.

Ashley Fletcher: They're ready to get him out of here. They’ve got the car running.

Since we aren’t allowed to talk to Driskill at the prison gates, we all meet up at a nearby gas station. It’s also a peach stand.

Maurice: We're now turning into Cooper Farms, which has a gigantic sign that says, “Peach ice cream: free samples.”

You can actually smell the peaches in the air a little bit. The mood is celebratory. Driskill hugs Mike Ware and Ashley Fletcher and everyone else, even people I’m not sure he knows.

Maurice: Larry, good to see you again.

Larry Driskill: Good to see you.

Ashley Fletcher: Hey Larry. How are you?

Larry Driskill: All right. How you doing?

Ashley Fletcher: Good.

Larry Driskill: Glad to be out now, anyway.

The man is beaming. He’s wearing jeans for the first time in seven years and they turn out to be too tight — I think his mom had to guess his size and guessed wrong — so combined with his big beard and baseball cap he looks a little like a hipster, but with a gigantic rodeo belt buckle.

Maurice: How are you feeling?

Larry Driskill: Right now? Kind of anxious thinking, ‘OK, I'm 60 years old. I'm fixing to be trying to find a job again. What am I gonna do?’

Driskill’s mom is anxious too. I can see it on her face. Which is reasonable. He’s free, but also not. Parole comes with restrictions. He’s supposed to go straight home. He can’t even stop for a first meal at a restaurant. So after people pose for pictures and hug again, we all disperse.

Driskill heads back to his mom’s house in Burleson, near Fort Worth.

A week later, I drive over to the house and spend most of the day with him.

Maurice: Was there any particularly strong feeling walking out of the prison after all these years?

Larry Driskill: I was just glad to see everybody out there waving at me. And I didn't have to worry about no loud TV waking me up in the morning or keeping me up late at night.

Maurice: You know, the first couple, two, three days you got out, what were the best experiences that you had?

Larry Driskill: Just to be able to move around more, not have to worry about somebody next to me getting mad at me. Because sometimes guys hear bad news and they'll flip on you in a second. When you're out and you're at home, you hope you don't have to deal with that too often.

In criminal justice circles, they call this “reentry,” as if you’re coming back from space. One thing that comes across about Driskill, as he tries to adjust to life on the outside, is just how practical he is. He’s very focused on, ‘Here’s what I need to tell my parole officer, here’s how I’m going to get a job, and here’s how I’m going to fix my truck.’

Larry Driskill: I've had them start it and run it while I was gone, just to make sure everything stays flexible, flyable, and it doesn't leak, but I still have got certain things I need to fix on it and work on. So when I’m ready, it's ready to go down the road again.

This is what he dwells on, rather than the emotional weight of the last seven years. And that doesn’t surprise me. For lots of Texans, nothing symbolizes freedom quite like a working truck.

And then of course there’s his legal case.

Larry Driskill: And I'm not worried about money or otherwise. I'm just worried about getting my name cleared, that’s all I am trying to do.

Driskill might not be motivated by getting compensation, but he is beginning to reckon with just how much he’s lost, how much has changed. While he was in prison, he and his wife had divorced.

Larry Driskill: I know time that I've lost, I can't make up. There's nothing I can ever do to get that time back. Hopefully, with God's help, I get my marriage back and my family and everybody comes back together.

There was huge damage to his relationships with his son and daughter. They have children of their own — and those kids may only have a hazy memory of their grandfather as a prisoner. Driskill is trying to stay optimistic about all these relationships, looking for comfort in his faith.

Larry Driskill: The way I look at it, Lord, I'm going to try to do what I can for you, for your glory. Not me, because I'm just a human body on this earth. But if you want me to be with my wife, you'll fix it. If there's somebody else you want in my life, you'll put them in my life.

But, Lord, if you want me to be by myself, that's fine. But when it comes time for my mother and my stepdad’s goodbyes, I will be here to take care of them. And then I'll go be on my own, if that’s what I have to do. But how am I going to spread your word, for your glory, if I'm by myself in the wilderness?

Driskill is caught between hope and hopelessness. He doesn’t know if the people he loves will ever let him back into their lives. But he did tell me that, since his release, he has run into his ex-wife a couple times.

Larry Driskill: I said, “Hi, youngster.” She didn't really say nothing.

At first, she wasn’t giving him anything back. But eventually, she teased him, about how he was so skinny he might blow away.

Larry Driskill: She said, “You ain't heavy enough.” She said, “You were always lightweight.” I said, “I've gained some weight since I've been gone.” She kind of tapped me on the arm. So I thought, ‘OK, whatever. If it's meant to be it will.’

Maurice: She's being friendly.

Larry Driskill: Yeah.

Driskill had previously told me he didn’t harbor any ill will towards James Holland. My question now, especially after hearing how much he’d lost, is, “Really?”

Larry Driskill: The only time I was upset with James Holland was, after the plea deal was done, I started to walk out of the courtroom and he just stood in the doorway, like he’s judging me or whatever. And he just stood there for a few minutes and I thought, ‘Just move out of my way. You've already done me in anyway, so move.’ That was the only time I've ever really been that upset with him.

But eventually, the sort of anger you would expect does come through.

Larry Driskill: I do everything I can to help everybody, and do as much as I can to help everybody, to get everything done and taken care of. Sometimes, I think it comes back and bites me in my backside. Like this situation. I was trying to be helpful, and I trusted the wrong people. I trusted the law, and I won't do that anymore.

Maurice: Are you saying you feel like Holland betrayed your trust?

Larry Driskill: Yeah. I feel like he threw me under the bus and backed over me a few times.

Before I met Driskill, years ago, his lawyer Mike Ware described him as an average guy. And it’s true. So many stories of false confessions involve obviously vulnerable people. One lesson, if you believe in Driskill’s innocence, is that any of us really could falsely confess.

Or, to say it another way, if this can happen in Texas, to a White guy on the latter side of middle age who works at the local jail, then what chance would anyone without those advantages have? And what stories of those people have we not heard yet?

I’m sure you’ve been following the wider political struggle over policing in the last few years, and the growing movement to make law enforcement less racist, less abusive, less deadly. Well, there’s a similar fight playing out in state legislatures about how to make sure that police don’t use extreme interrogations to throw innocent people into prison. And, yet again, the focus is on one key tactic that James Holland used with Larry Driskill: deception.

Richard Leo: Remember, I said earlier, any physical violence automatically will get [a confession] thrown out. You could do the same for lying and deception.

That’s Richard Leo, the law and psychology professor who helped us analyze Driskill’s interrogation.

Richard Leo: That would weed out a lot of weak cases.

According to Leo, other countries already have this rule.

Richard Leo: Lying and deception is not permissible in England, it's not permissible in many other countries that we compare ourselves to in the first world.

Here in the U.S., legislators in a bunch of states are starting to introduce bills to ban lying in the interrogation room. Just in the last few years, Oregon, Colorado and Utah, have all enacted bans. But they only apply to juveniles, not adults. So you actually can still lie to suspects under 18 — a.k.a. kids — in most of the U.S.

Not a single state has passed a law that bans lying to adults yet. But I can easily imagine, if someone proposes a bill like that in Texas, they might invite Larry Driskill or Chris Ax to tell their stories at the Capitol building.

As well as banning lying, Richard Leo suggests other changes that he says could reduce false confessions.

Richard Leo: You could put time limits on interrogation. We know that false confessions are usually the product of longer interrogations. And then you have other safeguards like jury instructions, expert witness testimony. So there's a range of things we could do to add more protections against letting that confession snowball into a wrongful conviction, where an innocent person goes to prison and has an uphill battle of trying to get out.

These solutions are all about banning or limiting tools used by police officers. But from the other direction, how might cops like Holland themselves improve their ability to solve murders, without raising the risk of ensnaring innocent people?

At the Los Angeles Police Department, some detectives have become known for a focus on simply getting the suspect to talk. You don’t interrupt or offer your own theories or turn up the pressure. You listen and dig into the contradictions in what the suspect is telling you. More and more, there is research showing these new methods are effective and less risky.

Richard Leo: The idea is that there's no rush to judgment, you don’t rely on body language, and there's no presumption of guilt, when you interview the person. Your goal is to get as much helpful information as possible. You don't interrogate them. You interview them, you let them talk and talk and talk and talk, and because you've thoroughly investigated the case, if they start to contradict themselves, then you challenge them with those contradictions.

But these alternative interrogation methods have a long way to go in terms of acceptance. There are roughly 18,000 law enforcement agencies in the US. That's a lot of detectives. I can’t imagine how long it would take to change the culture across the board.

And of course, it’s easy enough to argue against these tactics in cases when someone has spent years in prison, and then DNA emerges to prove they’re innocent.

But countless others aren’t so clear-cut. Having investigated Larry Driskill’s case for three years, I’ve come to see so many reasons to question his confession.

And aside from the interrogation itself, it just seems to be too much of a coincidence that Holland could have stumbled across the guilty guy in the first place. Remember, all he had to go on was one very dubious sketch made with a hypnotized witness, 10 years after the fact. And a phone call from a pawn shop owner who told him it looked a bit like his neighbor's handyman. That’s it. No direct physical evidence. No DNA. No other witnesses. I mean the chances of this process leading Holland to Bobbie Sue Hill’s murderer are just so small.

But still, as I sit here, Driskill has not been exonerated. While his early release on parole is a major victory for him and his lawyers, the State of Texas still labels him a murderer. Driskill’s team is anxiously waiting for those final hail-Mary DNA tests to come back. And don’t worry, I’ll update you if there’s any important news.

For now, he’s rebuilding his life.

Larry Driskill: My job is still to take care of family. And that's how I look at it. And to take what was wrong and just move forward and try to look positive, in the best outlook I can, at it. It's time to get a job, go do what I can, move on and try to make a better life for myself. And if my family wants to be in my life, great. If they don't, I'm not gonna hold it against them. Because to me, family's everything. Sorry.

Listening to Driskill, I find myself wondering how many people like him are still sitting in prison, with stories that have yet to be uncovered. And how many investigators are out there, following in James Holland's footsteps?

James Holland: You know what this is about? You want to know? It’s about closure. And that’s why they asked me to come in. Because I’m special.

CREDITS

“Smoke Screen: Just Say You’re Sorry,” is a production of Somethin’ Else, The Marshall Project and Sony Music Entertainment. It’s written and hosted by me, Maurice Chammah. The senior producer is Tom Fuller, the producer is Georgia Mills, Peggy Sutton is the story editor, Dave Anderson is the executive producer and editor and Cheeka Eyers is the development producer. Akiba Solomon and I are the executive producers for The Marshall Project where Susan Chira is editor-in-chief. The production manager is Ike Egbetola, and fact checking is by Natsumi Ajisaka. Graham Reynolds composed the original music and Charlie Brandon King is the mixer and sound designer. The studio engineers are Josh Gibbs, Gulliver Lawrence Tickell, Jay Beale and Teddy Riley, with additional recording by Ryan Katz.

This series drew in part on my 2022 article for The Marshall Project, “Anatomy of a Murder Confession.” With thanks to Jez Nelson, Ruth Baldwin and Susan Chira.