When Anthony Kent was released on parole from a Colorado prison, he was looking forward to getting back on his feet and registering to vote.

Eager to help, his mom, Teri Quintana, picked up a packet from the Bent County Department of Social Services in Las Animas. It was meant to provide someone on parole all the basic information needed to start their reentry process. But as she read through the paperwork, something seemed off. So she bounced in her black pickup truck between two other Eastern Plains counties to grab the same set of documents.

Tucked into the packets with the food and medical assistance program applications were two voting forms — the “Voter Registration Choice Form” mandated by the National Voter Registration Act (NVRA), along with the actual voter registration form. The Choice Form, which gives an applicant an opportunity to either accept or decline the opportunity to register, is used by the state to track registration efforts at government offices. But the secretary of state had not updated the form to reflect current voting rules, and some counties continued to hand it out despite a line stating that those on parole can’t vote.

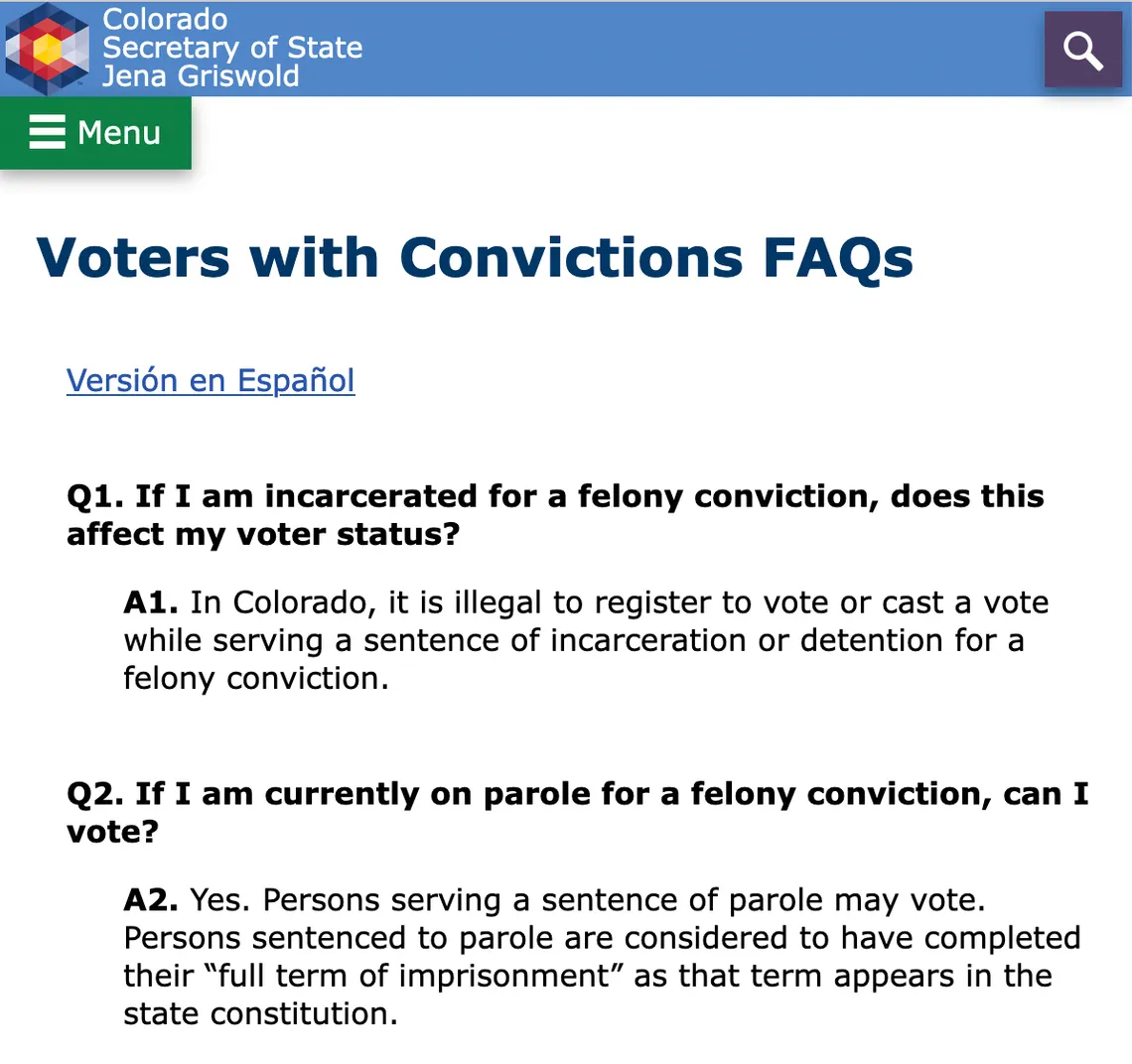

Quintana told herself that must be wrong. She couldn’t believe her son was ineligible to vote. She whipped out her computer and started searching. When she found the secretary of state’s website, it added to her confusion. The website contained the correct information reflecting the fact that in 2019, Colorado passed House Bill 1266, restoring the right to vote to more than 11,000 people who were on parole at that time.

The bill, passed by lawmakers as part of sweeping criminal justice reform efforts, expanded voting rights to people serving parole. But three years later, the state of Colorado has yet to update the information provided to anyone who receives the Choice Form. An analysis by The Marshall Project and The Colorado Sun shows no more than about 27% of people who have been on parole since 2019 have registered to vote since the law was enacted.

For formerly incarcerated people seeking to vote, attempting to register could have consequences: Registering to vote without being eligible is a Class 1 misdemeanor in Colorado, which is punishable by up to 18 months in county jail.

Kent wanted to vote after he got out. “All you can do is watch the news and watch the elections and watch the ticker on CNN,” he said. “And you can see every single vote being counted, and you know that you can’t vote. So as you're getting out, that’s one of the things you're looking forward to, you know — I need to have a voice in this.”

But, after seeing the Choice Form, he was quick to accept that he was not allowed to vote.

Frustrated by the confusion, Quintana fired off an email to the secretary of state's office: The form says parolees can’t vote, but the secretary of state’s website says they can, she wrote. “Could you please help clarify this for me?”

A day later, a lawyer from the secretary of state's office responded, confirming that people on parole can vote in Colorado.

“I believe the NVRA choice form still needs to be updated, and we will work on that as soon as possible — we are just waiting to confirm whether or not some other changes to the form are necessary before updating it,” the lawyer told Quintana.

The form in the assistance packet that Quintana picked up was last updated in May 2014.

Finding accurate information about voter registration in Colorado depends on where you look. The voter registration form on the Denver government website has not been updated since September 2018 and still states that people on parole cannot vote. The Colorado Secretary of State’s website, however, has an accurate, updated version of the form. The state Department of Corrections mandates that parole officers provide the accurate registration form and review it with parolees as part of their pre-release transition plan, but this does not include the Choice Form. When a Marshall Project reporter tried to obtain voter registration forms in Denver, she was handed an updated voter registration form without the NVRA form attached.

After The Marshall Project and The Colorado Sun started asking questions about the forms, a representative from the secretary of state said they had updated the form and alerted over 300 government offices to the change. The agency did not say when they updated the form, but the form they shared with the news organizations was last updated Jan. 24, 2022. The office “will continue to work closely with NVRA site coordinators and organizations responsible for registering voters, including those on parole, to ensure every eligible Coloradan is aware of the opportunity they have to make their voice heard in our elections,” the representative said.

Data shows that no more than about 27% of the more than 29,000 formerly incarcerated people affected by the 2019 law have registered to vote. Quintana and Kent believe this is at least in part due to the incorrect information handed out to parolees.

Few Formerly Incarcerated Colorado Residents Registered to Vote

In 2019, Colorado restored voting rights for thousands of people who were formerly incarcerated. That number has grown to nearly 30,000 since then, but a Marshall Project analysis found only 27% of them actually registered to vote, compared to a registration rate of about 88% in the state.

In 2021, the Marshall Project looked into the re-enfranchisement of those who were previously incarcerated and found that in the key states of Nevada, Kentucky, Iowa and New Jersey, no more than 1 in 4 previously incarcerated individuals had registered to vote in time for the 2020 election. Colorado’s rate of about 27% is similar to those states, and a small fraction of the 88% registration rate in the general population in the state. A survey conducted by the Marshall Project found that the longer people spend in prison, the more they want to be politically involved and vote, just like Kent.

“This particular population has never been a priority population,” said Justin Cooper, deputy director of the Colorado Criminal Justice Reform Coalition, whose organization helped to draft and pass the Colorado state bill in 2019.

Cooper works with government agencies that often interact with people on parole to help spread the word about voting. “These agencies, through the legislation, were mandated to provide public education,” he said. Cooper believes that formerly incarcerated people are a “significant constituency” that shouldn't face barriers to voting due to inaccurate information. Civic engagement is a powerful tool in reentry, he said. “What empowers them to reengage successfully is their ability to vote, their ability to engage civically, their voice to matter.”

John Sherman, who was incarcerated in Colorado for 35 years, said while on the inside, he and his peers “solved all the world’s problems.” They thought about politics, what was going on outside, the barriers to reentry like housing and employment and rebuilding a normal life, like learning how to navigate the internet. Voting seemed to be one more way they were locked out of society. He said the first time he heard he could vote was from a peer at a halfway house, and he didn’t believe what heard was true. “I didn’t know I had voting rights,” Sherman said.

Sherman said it would make sense to add civics education programming to the pre-release classes Colorado already offers on seeking employment and using computers. Illinois is the only state that requires civic education prior to release. A 2019 law established peer-taught programs on government, voting and current events in the Illinois Department of Corrections and Department of Juvenile Justice, though the pandemic has been a barrier to fully implementing the programs.

Christopher Uggen, a professor of sociology and law at the University of Minnesota, studies the reenfranchisement of those who were previously convicted of felonies. A 2004 paper he co-authored looked at the recidivism rates of voters and non-voters and found that those who had been arrested were half as likely to be rearrested if they were voters. Uggen says there are many reasons to suspect why this might be the case.

“Voting itself is partly an expression of this identification with one's fellow citizens and standing shoulder to shoulder with them in electing new leaders. And so, getting people to the voting booth is part of that process,” he said. “By locking people out, you're really reinforcing the idea that they are ‘other’ — that they are excluded.”

Both Uggen and Cooper are concerned about the ramifications if someone misunderstands the law, since casting a vote when you are prohibited from doing so is a crime in Colorado as well as other states. In Tennessee and Texas, for example, formerly incarcerated people were sentenced to prison for trying to register to vote. The Colorado voter registration forms warn that even registering to vote could be a misdemeanor. If there is any confusion, experts say people might err on the side of caution, causing further disenfranchisement.

Without his mother as his advocate, Kent says that he would have taken the Choice Form at face value. With help from his mom, he is now studying to become a paralegal. He wants to use what he has learned to help others navigate the criminal justice system.

“When you're involved in the legal system, you have no choice but to learn about it,” he said. “Because if you don't learn about it, then, you know, they'll just kind of give you whatever.”

Sandra Fish of The Colorado Sun and David Eads of The Marshall Project contributed data reporting.