PINE TOP, Kentucky — Just before sunset on Oct. 22, 2015, 53-year-old Stephen Brock was walking up and down the narrow gravel road near his trailer home, yelling, cursing and praying.

Neighbors later told police that Brock was erratic — nice one day, agitated the next. Many were aware he suffered from mental illness. But when they heard Brock making threats as he paced that evening, carrying what some thought was a gun, a neighbor called 911.

Kentucky State Trooper Luke Pridemore drove alone to the scene in rural Knott County. He found Brock hiding behind a bush, shouting that the government wasn’t going to take his land, and threatening to shoot, according to police records. The trooper returned to his patrol car and retrieved an M16 assault rifle.

Brock kept one of his hands behind his back and Pridemore thought it held a gun, he later told investigators. He fired three shots, killing Brock.

But Brock had no gun, only a length of rusty chain with a padlock on the end, which investigators found near his body.

Brock was the third person Pridemore was involved in killing in less than 17 months, according to state police records, which don’t indicate that he faced any consequences for the deaths.

Such a string of shootings is unusual; studies have found that only a quarter of police officers reported ever firing their weapons, and just 15% of those who did were involved in more than one incident.

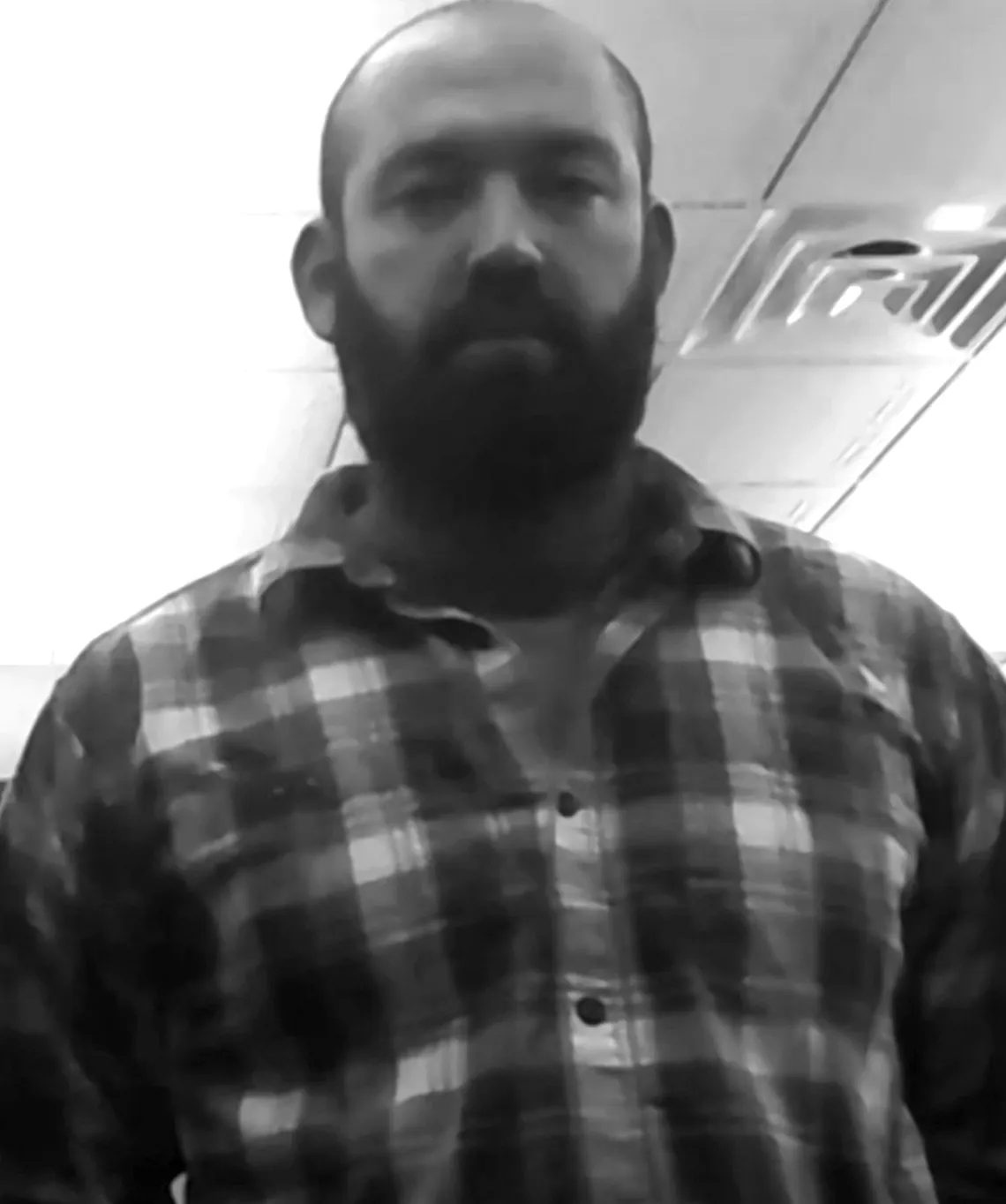

Reached recently by telephone, Pridemore, 36, declined to comment.

Pridemore’s track record helps illustrate the low level of accountability at the Kentucky State Police, whose officers shot and killed at least 41 people from 2015 through 2020. That is more fatal shootings than any other law enforcement agency in the state, according to an investigation by The Marshall Project and the Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting.

In fact, Kentucky troopers have killed more people in rural communities than any department nationwide, according to our analysis of data compiled by the Washington Post.

No Kentucky trooper was prosecuted for any of the 41 deaths we examined. About a quarter of those killed were not armed with a gun when state police shot them, and a majority were suffering from addiction or mental health problems.

The state police investigate their officers’ shootings with no outside oversight, a practice many police departments are abandoning and which some criminal justice experts and prosecutors say is problematic.

“I don’t think it should be done,” said Dave Stengel, the former commonwealth’s attorney in Louisville, citing the potential for conflicts of interest. “Everybody knows everybody else.”

Troopers don’t wear body cameras, although the Kentucky State Police says it is exploring the possibility of employing them. The lack of video evidence allows shootings to escape scrutiny, some experts say. We found some conflicting accounts from officers and witnesses about how fatal police encounters played out.

The state police declined our request for an interview. But the agency’s commissioner, Phillip Burnett Jr., defended its work, saying in a statement that he is “committed to protecting the integrity of all investigations, interactions with the public and our state officials as we conduct law enforcement in the right way.”

Sgt. Billy Gregory, head of public affairs for the state police, said that all shootings by its officers are reviewed by prosecutors who may take cases to grand juries. The agency “is committed to being transparent while ensuring the integrity of the investigation,” he said in a statement. He did not address questions about Pridemore.

The state agency that oversees the state police is “committed to full and fair investigations of every officer-involved shooting, including those involving the Kentucky State Police,” said Kerry Harvey, secretary of the Justice and Public Safety Cabinet.

There is no comprehensive government database of police shootings, and the Kentucky State Police would not provide a list of people shot to death by troopers. Using a combination of publicly available data and state police records, The Marshall Project and KyCIR built our own database of fatal shootings by troopers.

Troopers patrol wide stretches of Kentucky and are regularly dispatched to people’s homes. More than half the people killed by state police during the six-year review period were at a residence when they were shot, and almost three-quarters of those killed were armed with guns.

Pridemore’s first deadly encounter involved an armed man inside a home on Tranquility Lane in a little community near Hazard. In May 2014, six months after Pridemore was hired as a trooper, he was backing up an officer who reported being threatened by Larry Smith. After troopers arrived, Smith set the house on fire, according to police records.

Smith emerged holding a gun in his right hand and refused commands to drop the weapon, the records show. Four state troopers on the scene fired a total of 29 shots. Twelve were from Pridemore’s M16.

A grand jury declined to indict the officers.

The next fatal shooting Pridemore was involved in drew questions from witnesses about whether it was necessary — and whether the troopers were careful enough to protect bystanders. Neither of these questions was addressed by the Kentucky State Police inquiry into the death of Michael Asher.

On May 3, 2015, a county constable reported hearing gunshots from Asher’s camper on Doctor’s Row near Hazard. Pridemore was among the troopers who responded.

Neighbors said later that Asher was known for shooting at coyotes to protect his cats.

Troopers said that Asher pointed a gun at them from inside the camper. Pridemore and two other officers fired their weapons. Asher fell dead in the doorway.

A neighbor, Brian Carter, watched the shooting with his wife through a window of their nearby home. They couldn’t see Asher clearly because he was inside the camper. Carter said state police lined up “like a firing squad” with guns drawn. He heard troopers tell Asher to put the gun down several times before opening fire.

None of the troopers involved responded to requests for comment.

Six of the shots troopers fired at Asher went into a neighbor’s home, where some plowed through the living room and others were stopped by a brick fireplace, according to police records. Three residents were inside, including a man who used a walker.

The residents were not evacuated until after the shooting, according to police records. None of the officers were criminally charged.

Police gunfire that endangered bystanders cost a Louisville police officer his job last year. Brett Hankison fired shots that traveled into an apartment adjoining Breonna Taylor’s in March 2020. Hankison was the first to be fired, and the only officer involved in killing Taylor to face criminal charges: three counts of wanton endangerment for the bullets in the neighbor’s apartment. He has pleaded not guilty; his trial is scheduled for February.

From 2015 through 2020, Louisville Metro Police shot and killed 20 people, according to an analysis by KyCIR, about half the number fatally shot by Kentucky State Police over the same period. Louisville employs about 300 more officers than the state police’s 740 troopers, and the city’s police department receives far more public scrutiny for its actions than the state police.

Greg Belzley, a lawyer who has sued the state police several times, said he often gets contacted by people about alleged abuse by Kentucky troopers. But many are too intimidated to file a lawsuit, he said, or don’t have the financial resources to hire a lawyer.

“If it happens here in Louisville, that’s one thing,” Belzley said. “But if it happens where we say, ‘out in the state,’ it’s something entirely different.”

When it comes to police shootings in rural areas, he said, “There’s a sense that this is all better forgotten.”

Policing experts say state police escape scrutiny partly because video footage of killings by troopers in rural communities is rare. And there are sometimes differences between the way officers and witnesses describe events.

A single officer responded to a 911 call about Kenneth Huntzinger on February 7, 2017. Huntzinger had taken too much of the insomnia drug Ambien, his wife told police, and was hallucinating, acting aggressively and trying to drive away from their central Kentucky home in his pickup truck.

When a state police sergeant arrived, he pulled his weapon and in less than one minute, shot Huntzinger while his wife and son looked on, according to court records. Huntzinger died a week later.

Sgt. Toby Coyle told investigators he fired because Huntzinger was driving toward him and he was afraid he would be run over. Coyle declined to comment.

When the commonwealth’s attorney took the case to a grand jury, it did not indict, describing the force used as regrettable but justified.

But in a civil-rights lawsuit Huntzinger’s family filed, they said Coyle was not in danger of being hit by the truck. The fatal shot entered Huntzinger’s body after going through the driver-side window.

In court filings, Coyle’s lawyers said he had to shoot Huntzinger in part to protect other drivers he might encounter on the road.

A federal judge found “genuine issues of material facts” in the case and declined to dismiss it; it is set for trial on November 15.

The state police model has been to shoot first and ask questions later, said John Tilley, who from 2015 through 2019 was head of the Kentucky Justice and Public Safety Cabinet. Though the agency needs more oversight, he said, the legislature has been hesitant to scrutinize it.

“There's an unwillingness to address some of those tough issues,” Tilley said.

The Kentucky State Police created a special unit in 2017 to investigate state police shootings, as well as those of many local police departments.

The Louisville Metro Police Department turned to the state police to examine its shootings in the wake of Breonna Taylor's killing.

But state police have been far slower to release body camera footage and the names of city officers involved in fatal shootings than the Louisville police department, which used to provide information within 24 hours.

A spokeswoman for the Justice and Safety Cabinet said state police have “vast knowledge and experience” and are “committed to being transparent while ensuring the integrity of the investigation.”

The state police have been criticized for their failure to release public records. The Kentucky attorney general found in July that the agency had violated the state’s open records law when its officials denied a request reporters submitted for this story.

The state police violated Kentucky’s open records law more than any other government agency, according to a 2018 review by television station WDRB of state attorney general’s opinions on records disputes.

The state police also told us that at least nine investigations of officers’ fatal shootings going back as far as 2015 were still “open” and therefore not available to the public. The agency reversed itself after we supplied proof that the cases were closed.

Of the 41 fatal shootings by state police, The Marshall Project and KyCIR were able to identify 22 cases that prosecutors presented to grand juries. None of those officers were indicted. In 10 other cases, prosecutors decided that the evidence didn’t merit grand-jury consideration. What happened in the rest is unclear.

After Luke Pridemore shot and killed Stephen Brock in 2015, Brock’s daughter, Hayley Everage, thought the trooper would be held accountable once a grand jury heard the case.

Everage said her father had bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. He had been admitted to a psychiatric hospital six times since 2008, police records show.

But her hopes were dashed when a grand jury declined to indict.

“It was like what happened with my dad didn't matter,” Everage said.

The neighbor who called 911, Rebecca Pratt, watched from her front porch while Pridemore killed Brock.

“Honestly, I don’t see why he shot at him,” she said. “With somebody in his state of mind, you need to have more patience.”

Though the shootings apparently did not result in discipline for Pridemore, other incidents did.

In February 2017, he was suspended without pay for 60 days for an auto collision the previous year, according to police records. He was driving his agency-issued Chevy Tahoe nearly 90 miles an hour, and the other driver was seriously injured.

When Pridemore faced firing, it was over an off-duty assault, according to police records.

His cousin had been involved in an altercation at Karen Noble’s home in eastern Kentucky. At 1 a.m. on August 28, 2017, Noble called 911 to report an intruder: Pridemore.

According to a civil lawsuit filed by Noble and her teenage son, Landon Noble, Pridemore was dressed in police “tactical clothing,” with hard plastic knuckles under black gloves, and armed with a handgun. He entered the home without permission and struck Landon Noble in the face before slamming Karen Noble’s hand into a door and pushing her to the ground, according to the lawsuit.

Pridemore told state police investigators the Nobles assaulted him first and that he did not have a gun on him at the time.

An internal investigation substantiated the gist of Noble’s account, police records show. About eight months after the incident, the state police commissioner recommended that Pridemore be fired. In July of 2018, Pridemore resigned.

In May, Pridemore pleaded guilty to misdemeanor assault and misdemeanor criminal trespass and was placed on two years’ probation. The Nobles’ civil suit against Pridemore is pending.

After his career as a trooper ended, Pridemore was involved in another incident. In June of 2020, he pleaded guilty to charges including misdemeanor assault and misdemeanor resisting arrest, after he struck a woman and a local law enforcement officer at a bar, court records show. He was placed on two years’ probation and ordered to undergo counseling.

According to his LinkedIn page, Pridemore still maintains a connection to law enforcement. He is the owner of Prideheart Logistics, LLC, a process server and consulting business, which lists “use of force procedures” as one of his areas of expertise.

“I have a strong record of accomplishments,” his profile says. “My biggest attribute: Execution; I get things done.”

Alysia Santo is a staff writer at The Marshall Project. R.G. Dunlop is an investigative reporter with the Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting. Weihua Li, a data reporter for The Marshall Project, provided data analysis and reporting. A grant by the Fund for Investigative Journalism supported KyCIR’s work on this project.