Filed 6:00 a.m. 10.30.2018

May 6, 2015—Whereas, the City Council wishes to acknowledge this exceedingly sad and painful chapter in Chicago's history, and to formally express its profound regret for any and all shameful treatment of our fellow citizens that occurred; and . . .

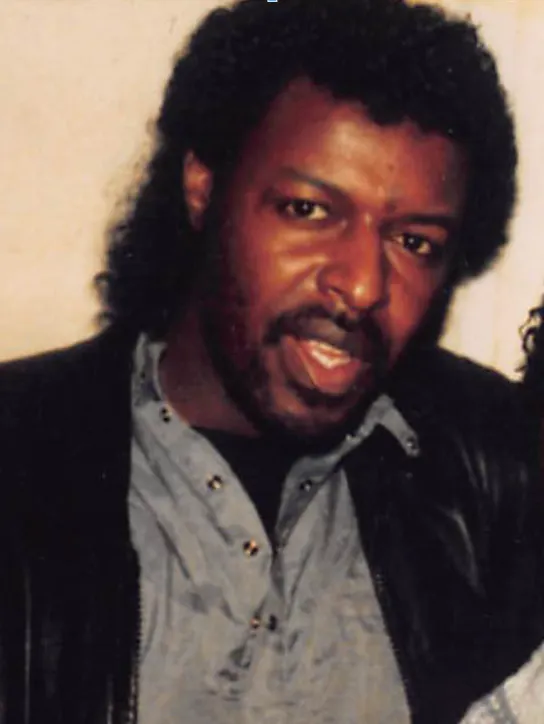

The nightmare starts in 1983. Darrell Cannon is driving a car down an expressway, looking for a place to dump a body. Since his elementary school days, he's been affiliated with a gang known as the Blackstone Rangers. By his mid-teens, he was a high school dropout working for a Blackstone leader named Jeff Fort, which is how he came to kill a man and go to prison the first time. Now he's out and back in the mix, and a few hours ago, another gang member named A.D. killed someone and asked him to help clean up the scene of the crime.

They find a spot, toss out the body and speed away as fast as they can.

A few days later, police arrest Cannon for the murder. He tells them he was just along for the ride, but they aren't in the mood to listen. They drive to a remote spot by a railroad track and stand him up in the road with his hands handcuffed behind him. One of the officers holds out a 10-inch cattle prod and another holds a pump-action shotgun. In an affidavit for one of the appeals he will file years later, he'll remember the warning one of the officers gave him: "You're in for a long, hard day. We have a scientific way of interrogating niggers."

On a spring morning more than 30 years later, Cannon wakes up and tests the weight of the day, waiting for the flood of emotion. Ever since a team of sadistic Chicago police officers shoved a shotgun into his mouth and tortured him into a series of false confessions, he's been dreaming of this moment. He dreamed about it all through the 21 years he spent in prison and his exoneration and release and the years that followed. Freedom was partial justice but still a very long way from real justice.

He still isn't sure he'll ever see real justice.

But he sure as hell isn't going to miss a chance to see it. He takes a shower, puts on a white-checked shirt, a tie and a black sweater vest that adds another touch of formality. He's too agitated to eat breakfast. He's in a hurry to get downtown to see history made, one way or another.

Today's reckoning began with an art project, of all things. Cannon had almost given up. Years had gone by. The evidence was out there: 118 black victims of the Chicago Police Department's team of torturers had been documented—some who were guilty of criminal acts and many who were exonerated and released. Members of the C.P.D. used electrical shocks and beatings, suffocated people with plastic bags and burned them with cigarette lighters, but faced no consequences from the state for their behavior. Police supervisors looked the other way, the state's attorney refused to investigate and used the dirty confessions to get convictions and the city fought off claims for damages in court. Community activists and the lawyers for the victims kept pushing. Amnesty International joined the fight, calling for an official investigation into the torture ring. In 1993, a decade after the torture was first exposed, the C.P.D. finally fired the leader of the ring, Commander Jon Burge. People were still fighting for justice two decades later, when a group of young Chicago activists called We Charge Genocide flew to Geneva to give a presentation to the United Nations' Committee Against Torture, and the U.N. responded with a report accusing the United States of violating international bans on torture, a startling low in international relations. Finally, in June 2010, a federal court convicted Burge on criminal charges—not for torture but for lying under oath when he denied torturing people in a civil trial brought by one of his victims.

But that still didn't feel like real justice, not to Cannon or the other torture victims—who prefer to be called "survivors." Most of them weren't even offered therapy. Rather, most of them were ignored, even as the world responded with horror to the American torture of detainees in Iraq.

In 2012, when a group of activists and artists organized a "speculative memorial" to support them at the Art Institute of Chicago, a work of imagination by a human-rights attorney named Joey Mogul caught their attention in an unexpected way. In the spirit of the 18th-century satirist Jonathan Swift, Mogul had created a mock-up of an official city ordinance mandating reparations to the torture victims. It was intended as a work of art.

In the context of American history, the idea is explosive. The U.S. government has long resisted attempts to coax loose even an apology for slavery, much less give serious thought to reparations. Black members of the U.S. Congress have been introducing a bill repeatedly since 1989 calling for just a study of reparations—damages for America's founding sin—without getting even close to a vote. Most Americans consider reparations nothing but a pet project of angry black nationalists.

After the art show, Mogul and the other activists had an epiphany: Why not? They began researching the fight for reparations from regimes in Argentina and Kenya and Chile, for the Japanese Americans who were put in camps during World War II, for the women from North Carolina who were sterilized and for the survivors of the white riot that wiped out Rosewood, Florida. They met with a U.N. special rapporteur on torture, who told Mogul that the reparations Chile had paid to the victims of Augusto Pinochet's brutal dictatorship included free health care and education. Mogul added another clause to her reparations ordinance, giving the torture victims free tuition to city colleges.

In Chicago, public opinion was outright hostile on the topic of reparations for a group of former convicts, including some who were career criminals—Cannon, for example, was on parole after serving 12 years for murder when he was arrested. Over the next two years, the movement grew through Sunday-afternoon meetings, petitions, marches, a Twitter campaign to pressure Mayor Rahm Emanuel, makeshift memorials, sing-ins, teach-ins, public train takeovers and church talks. A pair of city council members named Howard Brookins and Joe Moreno sponsored Mogul's reparations ordinance. A well-known criminal justice reformer named Mariame Kaba, who joined Mogul's advisory board, told me: "I consider the reparations ordinance to be an abolitionist document. It's an expansive way of demanding a form of justice, and it had specific requests and demands that were non-carceral demands that tend to the needs of survivors."

At one rally, a survivor named Mark Clements—who spent 28 years in prison for a confession tortured out of him by Burge—spoke to the crowd. "I am asking for the entire City Council to have a heart. I was 16 years old. I can never express this enough. Sixteen years old, handcuffed to a ring around the wall and having my genitals grabbed and squeezed and called a nigger boy."

Today, May 6, 2015, the city is finally going to bring the matter up for a vote. If council members decide for the massive class of police torture victims, it will be the first time in the history of the United States that African Americans who suffered from organized government violence win the right to reparations.

As Cannon heads up the steps, he straightens his tie.

The "scientific method" of interrogation came courtesy of Burge, a former military police investigator in Vietnam. Born just after World War II, he grew up in a white enclave on Chicago's South Side called South Deering, where his father worked for the phone company and his mother wrote a fashion column for the local newspaper. He was 5 when a black family moved into the neighborhood, and his neighbors responded with rocks and racial slurs. In 1960, when he was 13, South Deering was 99 percent white, but by the time he graduated from high school, the town was changing profoundly, with black parents demanding access to an equal education and local politicians and behind-the-scenes powers all dead set against it. Burge enlisted in 1966 and went to Vietnam two years later. On his return, he joined the police department and quickly made detective. He was sent to a station called "Area 2," which covered a large swath of the South Side—including South Deering.

He tortured his first documented victim in 1973, a year when the city clocked 864 murders. His officers had arrested a man named Anthony Holmes on suspicion of murder and wanted him to identify an accomplice. When Holmes refused, the officers left him handcuffed in an Area 2 investigation room and went to find Burge. A few minutes later, Burge strolled into the interrogation room with a mysterious box in a brown paper bag. The box had a hand crank on one end and two wires with alligator clamps coming out the other end. According to trial testimony decades later, Burge then picked up the alligator clamps and barked, "Nigger, you're going to tell me what I want to know." He fastened the alligator clamps and pulled a plastic bag down over Holmes's head, warning him not to bite through it when the pain hit. Then he started turning the crank.

When the first blast of electricity rolled through him, Holmes bit through the plastic bag—a reflex reaction that opened a vent for his screams of agony. Then everything went black, and when he woke up, Burge was putting a fresh plastic bag over his head—the terrible panic of suffocation compounded the pain of the electric shocks. A rumor in the department had it that Burge had first perfected these techniques on North Vietnamese prisoners of war.

Burge released another blast of electricity. Again Holmes felt a thousand needles piercing every nerve in his body, and they kept on piercing and piercing until his brain couldn't take it and everything went black again.

When he woke up, Burge was laughing and preparing his infernal box—he called it "the nigger box"—for another round. Holmes broke. He confessed to a murder he didn't commit. During the decades he spent in prison, as his wife divorced him and eight members of his family died, his memories of the torture stayed fresh. They were still fresh decades later, when he offered a Violent Victim Impact Statement about that night during one of the many attempts to bring Burge to justice:

I still have nightmares, not as bad as they were, but I still have them. I wake up in a cold sweat. I still fear that I am going to go back to jail for this again. I see myself falling in a deep hole and no one helping me to get out. That is what it feels like. I felt hopeless and helpless when it happened, and when I dream I feel like I am in that room again, screaming for help and no one comes to help me. I keep trying to turn the dream around, but it keeps being the same. I can never expect when I will have the dream. I just lay down at night, and then I wake up and the bed is soaked.

The torture ring was great for Burge's career. Because of his high clearance rate, he was promoted to sergeant and then lieutenant—even though he was so open about his methods that he sometimes displayed his "nigger box" on a table at the police station.

By the time Darrell Cannon's turn came in 1983, Burge had expanded his repertoire to include electric cattle prods and simulated executions that didn't seem very simulated at all. On that dismal side street by the railroad tracks, the officers with the cattle prod and the shotgun stepped closer. Years later, just like Holmes, Cannon would testify to memories unrelieved by the passage of time:

The officer with the pump shotgun played Russian roulette on me by showing me a shotgun shell, then turning his back to me, says, "Listen, nigger," and all I could see was his back and not the shotgun nor the shell, and I heard two clicks of the shotgun being clicked. Then he turn to face me forcing the barrel into my mouth saying, "Nigger! Are you going to tell us where A.D. is?"

Cannon said he didn't know, which he didn't, but the officer with the shotgun—Lt. Peter Dignan, Burge's second-in-command—shoved the shotgun into his mouth again. The other officers shouted, "Blow that nigger's head off!" like a cheering section. But Cannon still didn't know where A.D. was, so Dignan played another round of turning his back to load the shotgun and coming back around to shove it into Cannon's mouth. This time Cannon was sure he was a dead man, and when Dignan pulled the trigger with a heavy metallic click, the burning in the back of his head was so intense that it took Cannon several long moments to persuade himself that he was in fact not dead.

Dignan and the officer with the cattle prod—a sergeant named John Byrne—tried another approach. They threw him in the unofficial vehicle they'd so ominously chosen to use that night—in the drawings Cannon would later produce for the court trials, he always wrote "blue car" in the label—and once in the car, they pulled Cannon's pants down around his ankles, armed the cattle prod and pushed it into Cannon's crotch. When that didn't produce the answer they wanted, they took him to the pound. They had the car Cannon had been driving the night he'd dumped the body. "Show us where everybody was sitting," they demanded. When he said he didn't know, Byrne hit his crotch with another blast of electricity, and this time he kept it up for a solid 30 seconds.

Cannon couldn't take any more. The torture team had broken him. He'd say anything they wanted, he begged. He'd sign any document, admit to killing the president of the United States, just please God make it stop.

Three years later, Byrne was promoted to commander.

May 6, 2015—Whereas, the City Council recognizes that words alone cannot adequately convey the deep regret and remorse that we and our fellow citizens feel for any and all harm that was inflicted by Burge and the officers under his command. And yet, words do matter. For only words can end the silence about wrongs that were committed and injustices that were perpetrated, and enable us, as a City, to take the steps necessary to ensure that similar acts never again occur in Chicago; and . . .

The seeds of Burge's undoing were planted in February 1982, when two officers from the C.P.D.'s gang unit were shot to death by unknown assailants, and the police superintendent put Burge in charge of the feverish manhunt that followed, said to be the largest in the city's history.

For five days, Burge and the officers under his command kicked down doors and made threats, taking some back to the station for more sustained punishment. On the fifth day, they got a tip that two brothers had committed the shootings, Andrew and Jackie Wilson. Burge and his core group of detectives made the arrest. They took the Wilson brothers straight back to the Area 2 headquarters for their usual "interrogation." They focused on Andrew because the tipster said he was the shooter, punching and kicking him; then they put a plastic bag over his head and burned him with a cigarette lighter before, finally, taking out the box. Burge handcuffed Wilson to a hot radiator, attached one of the alligator clips to his nose and the other to his ear, and started cranking. The blast of current jolted Wilson against the radiator. Burge did it some more and moved one of the clips to Wilson's lip. When he was tired of that, he moved the clips to Wilson's penis and testicles. After 15 hours, with disfiguring burns from the radiator on his face and arms, Andrew Wilson finally confessed.

In the normal course of things, the Wilson case would have been a double murder of C.P.D. officers solved in record time, another brilliant success for Jon Burge. But this time, when Burge and his men tried to drop Wilson off at the county jail for processing, the supervisor took one look at him and called the jail's medical examiner. When the examiner's report reached Dr. John Raba, the jail's medical director, he was so outraged, he wrote a letter to the C.P.D. superintendent, Richard Brzeczek. "All these injuries occurred prior to his arrival at the jail," Raba said. "There must be a thorough investigation of this alleged brutality."

Brzeczek sent the letter to the Illinois state's attorney, Richard M. Daley, asking for marching orders. Daley decided to skip the investigation, and his office proceeded to use the fruits of Burge's torture session to put Jackie Wilson away for life. Andrew Wilson got a death sentence.

For the next six years, Burge and his crew—now emboldened, and calling themselves "Burge's Asskickers"—continued on as before, only worse. They tortured a man named Michael Tillman over a four-day period in 1986, threatening him with a gun to his head, smothering him with a plastic bag, burning him with a cigarette lighter, pouring 7UP in his nose and beating him with a telephone book. Desperate, Tillman confessed to charges of murder and rape for which he wasn't responsible—a few weeks later, the C.P.D. caught the real killer—but Burge still turned Tillman's false confession over to Daley's prosecutors, and Tillman was convicted. He spent more than 20 years in prison.

In 1988 Burge tortured a murder suspect named Ronald Kitchen for 16 hours and emerged with a confession so explosive it got Kitchen sentenced to death. Never mind that the confession wasn't true.

Meanwhile, Raba's letter worked its way through the court system—"All these injuries occurred prior to his arrest"—and Cannon, like Wilson and the others, sat in prison. He sent his mind back over and over what had happened, and eventually he realized there was an ugly but tantalizing shred of hope: I'm not the only one. He couldn't be. The whole thing was too coordinated. "You just don't up one day take a man to isolated areas to play Russian roulette," he said later. "This was a systemic pattern."

If he could find the others, he thought, together they might be able to get someone to listen.

Unknown to him, it was already happening. The Raba letter and Wilson's appeals had entered the public consciousness and were soon joined by lawsuits filed by other victims of Burge's evil squad and a group of civil-rights lawyers accustomed to the nasty side of Chicago. After all, it was in Chicago that Martin Luther King Jr. was attacked while marching for fair housing in a white South Side neighborhood. It was Chicago, too, where a neo-Nazi group had located its 1970s headquarters. It was here that a leader of the Black Panthers, Fred Hampton, was killed while he was asleep in his bed—by a member of the C.P.D. during a bogus raid.

Andrew Wilson filed a civil lawsuit against the city of Chicago in 1986. As the case proceeded, his lawyers, led by Flint Taylor of the People's Law Office, the same firm that represented the Black Panthers, received a series of explosive anonymous letters from a source in the C.P.D. who referenced the country's biggest cover-up in the nickname he chose: "Deep Badge." He said the scandal was so pervasive it even included the state's attorney (and future mayor), Richard M. Daley, who knowingly used coerced confessions to convict many black prisoners. Soon Wilson's attorneys came across another victim named Melvin Jones. When they visited him in jail and heard him talk about an "electric-shock box," they knew they were on the right trail. If they could find more, Wilson had a chance.

Wilson's trials and appeals went on for years. The first ended in a hung jury. In the second, the jury found that Wilson's constitutional rights had been "violated" but still exonerated the officers—on the grounds that Chicago had a de facto policy authorizing its officers to physically abuse people suspected of killing or injuring a police officer. But activists and community groups continued the fight to expose and punish the torturers until finally, in 1991, the C.P.D.'s Office of Professional Standards advised the department to fire Burge and two of his henchmen.

They weren't fired. Instead, the officers were suspended—with pay.

Nevertheless, the O.P.S. sent in another investigator, Michael Goldston, who compiled the evidence of systematic torture into a document that came to be known as the Goldston Report. Although the C.P.D. fought a long legal battle to keep the report secret, the courts ruled in 1993 against the department, and finally a crack opened in the blue wall that had protected Burge and his torture crew. Burge was fired and two of his deputies were suspended. To official Chicago in 1993, that seemed like a perfectly adequate punishment for a group of co-conspirators who engaged in decades of sanctioned, programmatic violence, especially since Daley and the CPD were vulnerable to charges of knowingly looking away. They even let Burge keep his pension.

May 6, 2015—Whereas, the apology we make today is offered with the hope that it will open a new chapter in the history of our great City, a chapter marked by healing and an ongoing process of reconciliation; and . . .

Chicago has a long history of virulent institutional racism. In a city where the rate of false confessions has been three times the national average, it makes sense that protest movements would also be three times as intense. And in response to the torture scandal, new activist groups like the Campaign to End the Death Penalty and the Death Row 10 emerged, supporters of the 10 men who were on death row because of confessions Burge and his men tortured out of them. Working together with the support of a wide variety of similar organizations, the C.E.D.P. and the Death Row 10 began a series of passionate hearts-and-minds campaigns in the city. In one, some of the 10 called in to community meetings to tell their stories on speakerphone. In another, the C.E.D.P. helped rally supporters of the Death Row 10 as one of its members—Mary Johnson, the 85-year-old mother of one of Burge's victims now doing life in an Illinois supermax because of his own coerced confession—filed a civil complaint against Burge. With the dignity of her age and a heart to match, she made a personal visit to death row and emerged with a report that struck a note too human to ignore. "I saw so many people who didn't have anybody," she remembers now. "I was like their mother they hadn't seen in years." Moments like that energized the movement.

"The moms went everywhere with big signs," says Alice Kim, a leader of the C.E.D.P. "Their willingness to lock arms with attorneys and activists put a human face on their sons' cases."

The protests and the weight of history finally had an impact. In 2000, the governor of Illinois—a Republican named George Ryan—called a halt to all executions and conducted a review of all death-penalty cases. When it was finished three years later, Ryan pardoned four outright—Aaron Patterson, Leroy Orange, Madison Hobley and Stanley Howard—and commuted the death sentences of the other six.

But even after that stark admission that justice in these and similar cases had been fatally compromised, Burge was still a free man enjoying his retirement. It seemed that no one anywhere had the will to face the truth of what had happened here. The Illinois legislature appointed a special attorney to investigate the Burge torture ring but dropped the case four years and $7 million later with a whitewashed report that didn't even mention the word "torture."

By that time, former Cook County state's attorney Richard M. Daley had long since moved on to a different job—mayor of the city of Chicago. And to protect against an unflattering review of his decision-making as state's attorney, Daley had no incentive whatsoever to dig into the dark recent past of the C.P.D.

But in the spring of 2004, a story of torture in a foreign land—the Abu Ghraib military torture scandal—aroused universal condemnation and swift reaction in Washington and around the world. The long-suffering black communities on the South Side and West Side saw the obvious parallels to Burge. And they, too, saw the bitter irony that the world seemed to care a great deal about tortured Iraqis and not at all about tortured black people in Chicago. This gave a community activist named Standish Willis an inspired idea. "The president at the time was [George W.] Bush," Willis remembers. "Our military was torturing people, and he was saying we're not really torturing. That's what made me think, Take it international."

Willis started a group with a name that couldn't have been more direct: Black People Against Police Torture. Sitting in his downtown law office today, surrounded by photographs of people like Nelson Mandela and Dick Gregory, Willis remembers taking evidence of the Chicago torture squad to the Organization of American States' Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in 2005. A year later, Joey Mogul of the People's Law Office carried the same message to the United Nations Committee Against Torture in a fiery speech that climaxed in a shocking mixture of bitterness and defiance: "For the past 30 years, the United States has failed to comply with Article 2 of the Convention Against Torture," she said. "Back in 1982, Mayor Richard M. Daley was informed of specific torture allegations made by Andrew Wilson when he was Cook County state's attorney. As state's attorney and as mayor, he has not only failed to investigate, but has continued to suppress evidence of this documented pattern of torture. We have exhausted all remedies locally."

May 6, 2015—Whereas, just as a wrongful act followed by an apology, forgiveness, and redemption is part of the shared human experience, so too is the widely held belief that actions speak louder than words; and . . .

The mistake that would finally send Burge to prison came during his testimony in another civil lawsuit filed by a victim-survivor of the torture ring, a man named Madison Hobley. When Hobley's lawyers asked Burge if he ever used techniques including but not limited to sleep deprivation, withholding food, racial slurs, the use of objects to inflict pain or machines that deliver an electric shock or verbal or physical coercion—Burge gave a firm reply: "I have never used any techniques set forth above as a means of improper coercion of suspects while in detention or during interrogation."

In June 2010 he was convicted on two counts of obstruction of justice and one count of perjury and was sentenced to four and a half years in prison, twice the amount recommended by the federal probation guidelines. "This sentence delivers a measure of justice, which Burge obstructed for so long," the prosecutor said. But because Burge had not been compelled to pay or even answer for his true crimes, the sentence felt less like comfort to his victims and their families than like another slap in the face.

"It didn't necessarily feel like justice," Alice Kim remembers. Some of the survivors had spent decades in prison for crimes no worse than the ones Burge had perpetrated right under the noses of his direct supervisors and Richard M. Daley.

But instead of accepting the outcome, Chicago's activists dug in. An important new group emerged called the Chicago Torture Justice Memorials, which held the pivotal "speculative memorial" to the torture-ring survivors at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. The impact of Joey Mogul's "official city proclamation" granting reparations turned the minds of the activists to the history of previous struggles against officially sanctioned crimes. As the marches and rallies caught fire, cracks started to appear in the dam of official denial. The first broke open in 2013, when the Chicago City Council issued a settlement of $12.3 million to Ronald Kitchen and Marvin Reeves, who had spent more than 20 years in prison before being given certificates of innocence and released.

Energized by the settlement, the activists continued to press their advantage. Cash settlements weren't enough, they insisted—as Roy L. Brooks put it in "When Sorry Isn't Enough: The Controversy over Apologies and Reparations for Human Injustice," a settlement can mean resolving differences without admitting guilt or accepting responsibility, but reparations are settlements that include "atonement for the commission of an injustice." That's what the victims of the Chicago Police Department wanted—atonement.

As the 2015 election approached, with the national news full of black men killed by white cops, of "I can't breathe" and "Hands up, don't shoot" and of hundreds of reparations activists and supporters marching downtown, waving black flags stitched with the names of the survivors and chanting, "Reparations now!" first-term mayor Rahm Emanuel started to get nervous.

Ten days before the primary, he decided to make a deal. Over the course of four intense meetings, the negotiators for the protestors—including Flint Taylor and Joey Mogul, the author of the speculative reparations declaration—pressed the justice of their cause on Emanuel's lead negotiator, Steve Patton, asking for a package of $20 million. Patton resisted, arguing that a package that large would open the city to more lawsuits and more payments.

Negotiations took on the air of history. How much injustice could a single resolution correct? But a deal was struck and sent to the Chicago City Council. And now, on the sixth day of May, 2015, the moment of reckoning had arrived. Men like Darrell Cannon put on white-checked shirts and ties and headed downtown to witness Chicago finally shaken out of its indifference and denial.

May 6, 2015—Whereas, for this reason, the City of Chicago wishes, in some tangible way, to redress any and all harm that was suffered at the hands of Jon Burge or his subordinates by extending to those individuals who have a credible claim of torture or physical abuse ("Burge victims") and to the members of their immediate family, and, in some cases, to their grandchildren, a variety of benefits.

The clerk read the resolution, and the legislation passed. From a total of $5.5 million, each of the 57 documented torture-ring survivors would get nearly $100,000. All survivors and their families would have the benefit of free Chicago junior college tuition and a counseling center; Chicago public schools would teach the history of police abuse to all eighth and 10th graders, and there would be a public memorial erected in the city.

Today, Patton remembers the impact of the protestors' arguments, especially the passion behind them, which showed him the deep roots of the black community's outrage. "It became clear to me and others on the city side that we really weren't going to be able to bring closure to this dark, awful historic fact and chapter in the city's history without reparations," he told me. "It wasn't so much the money for money's sake. It was to really vindicate those wrongs and to really—in a meaningful way—acknowledge them. You have to put your money where your mouth is."

For Cannon, the moment was overwhelming. As he remembers it now, he was "truly under the assumption that politics would rule the order of the day and reparations would not be handed down to black men in the city of Chicago."

But the impossible had happened. If Chicago could lead the country in something other than its murder count, maybe the old prophets were right, maybe the last would finally be first, maybe black Americans would, at last, join in the promise of the promised land . . . maybe.

Burge had just gotten out of prison for lying under oath when the clerk announced the reparations package. He was enjoying a comfortable retirement in Apollo Beach, the Florida boating community featured on HGTV's "House Hunters." In the rare photographs that appeared in the media, he was beefy and white-haired but still had the same look of righteousness and bulldog determination. He made no public comment about the reparations announcement.

I decided I'd be the one to dig it out of him. Once I tracked down his number, I sat down and froze. As a black woman who burns with rage at the details of this story, at the horrors inflicted on those helpless black men, could I really conduct a civil conversation with this man?

I stalled by searching for information about Burge's recent activities.

I found very little. A few deposition videos he gave in other torture cases float around on the internet, but even there the pickings are slim—when asked in a 2005 court deposition whether he observed or participated in the use of electric shock against North Vietnamese POWs during the war, he invoked the Fifth Amendment. He pleaded the Fifth again during a deposition in 2015, but that time he succumbed to a flash of anger that offered a glimpse of his real feelings toward Flint Taylor, the lawyer in dogged pursuit of him: "I exercise my Fifth Amendment rights—even though I would like to say you are a liar."

Taylor got a copy of an unpublished email Burge sent to a Chicago Sun-Times reporter and shared it with me: "I find it hard to believe that the city's political leadership could even contemplate giving 'reparations' to human vermin." After I read it through for the first time, I sat at my desk in a state of nausea and fury. The word vermin crawled across my mind. How could any American citizen say a word so rank with associations to Nazi propaganda? How could he say it so casually?

Finally, I picked up the phone.

The man who answered sounded suspicious. "What do you want?" he asked.

I told him I was a reporter calling about the reparations decision.

"No thank you," he said, and the connection went dead.

I was relieved, I have to admit. But I kept brooding about that word. I thought about the media's habitual tag for black urban communities, "crime-infested neighborhoods." The phrase makes you think of filthy insects that infest our houses and multiply so rapidly that it's like they're just begging to be exterminated. We describe black neighborhoods as "war zones," which makes us think of enemies and conquering armies. Is it a surprise that Burge came back from an actual war zone with the idea that a good and honorable American could use a "nigger box" on other Americans?

Cannon, on the other hand, is eager to talk. I meet him at a no-frills diner on the South Side, and the first thing he says to me is that he took two Pepto-Bismol to calm his nerves. Ever since I called, he says, the whole ordeal had come flooding back—the torture, the trial, the nine long years he spent sleeping on a concrete block. Even after they exonerated him in 2004, they kept him in prison for another three years just to get all the legal wrinkles smoothed out. But for him the wrinkles—his nightmares, his constant edginess, the way he sweats whenever he sees a police officer—will never be smoothed out. "Most of the time," he says, "when I relive what's happened to me, I get so mad that I start crying."

Only one thing would really help, he says. "The day I'm told that each one of them who tortured me is buried six feet under, I can start thinking they are burning in hell and constantly screaming and being tormented. Maybe then I'll have peace of mind."

The reckoning brought by reparations makes some segments of Chicago society very unhappy, however. The Fraternal Order of Police, for example, responded with a strongly worded protest: "The FOP and its members finds any coercion of a witness or a suspect repugnant. With this in mind, the FOP believes that a thorough review of these cases is appropriate due to the increasing evidence of misconduct in the wrongful conviction movement. That evidence includes the strong possibility that some wrongful conviction claims are false and some may even be fraudulent. The evidence of false affidavits, obtained through chicanery and bribery, is particularly troubling."

In the end, the Burge scandal was an enormous financial blow to the city of Chicago: $29 million was paid to lawyers defending the city; $83 million was paid in individual settlements, judgments and reparations. And $863,000 is the amount of Burge's pension, which, despite his conviction on two counts of obstruction of justice and one count of perjury, the Illinois Supreme Court ruled he could keep.

There are also county costs and state payments to exonerated men. In total, a whopping $131 million has been spent defending Burge and paying for his wrongdoing. As many as 20 men who were tortured by Burge are still in prison. Their fight for freedom continues.

On a fall evening in 2017, eight teachers are sitting at desks in a classroom at the Chicago Teachers Union listening to a presentation from Jen Johnson, the union's educational issues manager. "Your students come from varied backgrounds," she tells them. "They may hear 'My uncle is a police officer' or 'My uncle is a gang member.'"

Starting in the 2017–18 school year, as another feature of the reparations package, the Chicago public school system introduced a new required text for all eighth and 10th graders: "Reparations Won: A Case Study in Police Torture, Racism, and the Movement for Justice in Chicago." Today's meeting is a "professional development session" on how to teach what has come to be called "the Burge torture curriculum." This was also one of the main goals of the activists, who argued that education was the best long-term answer, the only approach that could lead to real transformation. Students have to learn the history and see that it isn't about attacking police officers and police work but rather showing the systemic nature of racism. The lesson plans compare Chicago's experiences with similar national events (the current wave of police shootings very much included) and explore the reasons city leaders took so long to respond to the torture ring, Chicago's long history of racism and segregation and its equally long struggle for justice. They also include regular hints of hope, such as a detail that nods to Martin Luther King Jr.'s vision of the arc of the universe—Burge was hired just as President Richard Nixon started the War on Drugs and was fired not long after the videotaped police beating of Rodney King.

Chicago reparations also include healing, mentally and physically. The new Chicago Torture Justice Center carries the "sorry is not enough" vision forward by sharing its South Side headquarters with a public health clinic. Together they offer both the clinical space to treat physical traumas and the Justice Center's more therapeutic environment, which includes case managers to coordinate public services as well as private therapy rooms stocked with warm drinks and soft lighting—it is the United States' first official trauma center for the victims of its own police forces. "Some of the pieces that come up are related to not just the torture that occurred on a day or series of days but the incarceration that lasted decades," says the center's executive director, Christine Haley. "Not seeing their children grow up, not being able to parent, children who died while they were incarcerated, relationships and marriages that ended."

Activists are also pushing for a real memorial, and once again there's an overlap with America's broader history—as they see it, their memorial to the torture victims will be the best response to the current fury over Confederate memorials, raising the old question underneath so much of our history: Whom do we choose to honor, and why? If we get better at answering that question, maybe we can turn the hints of hope in Chicago's torture curriculum into something better—not just hints but harbingers. After all, remember which city we're talking about and the vast and powerful forces that were once arrayed against the anti-torture activists. Remember the state-sanctioned murder of Fred Hampton and the Nazi marches. Remember the racist housing policies. Remember the nigger box.

If Chicago can change, the rest of America has run out of excuses.

Editor's Note: Jon Burge died on Sept. 19, 2018.

Natalie Y. Moore is Chicago NPR-affiliate WBEZ’s South Side reporter, where she covers segregation and inequality. She is also the author of "The South Side: A Portrait of Chicago and American Segregation" which won the 2016 Chicago Review of Books award for nonfiction. She is also coauthor of "The Almighty Black P Stone Nation: The Rise, Fall and Resurgence of an American Gang" and "Deconstructing Tyrone: A New Look at Black Masculinity in the Hip-Hop Generation."

From

and