He’d spent years wondering when the other shoe would drop. The revelation had taken him by surprise — the best possible thing that could have happened under the circumstances, his lawyer said — and yet the promise of it weighed too heavily for him to completely go along with it. Part of him was sure it wasn’t true at all.

He’d told his girlfriend, Jasmine. She didn’t seem to believe it, either. Maybe it was that even this new, shorter prison sentence still seemed too long to someone barely 20. Or maybe she didn’t like how the news seemed to change him. She bristled when he got serious and talked about marriage. Her visits slowed, then stopped. He kept her picture on the wall of his cell.

Only after Rene Lima-Marin walked out and the gate of Colorado’s Crowley County Correctional Facility shut behind him, on April 24, 2008, did he finally decide he didn’t have to worry anymore. He was 29 years old and a free man, released after serving a decade of what had first been a sentence of 98 years.

Jasmine came to see him right away. They stared at each other for what seemed like an hour. She said he looked weird. He was thinner, his long hair cut short. But he could not be denied now, standing there in person. He had told her he was going to change in prison, and he told her now that he’d done it.

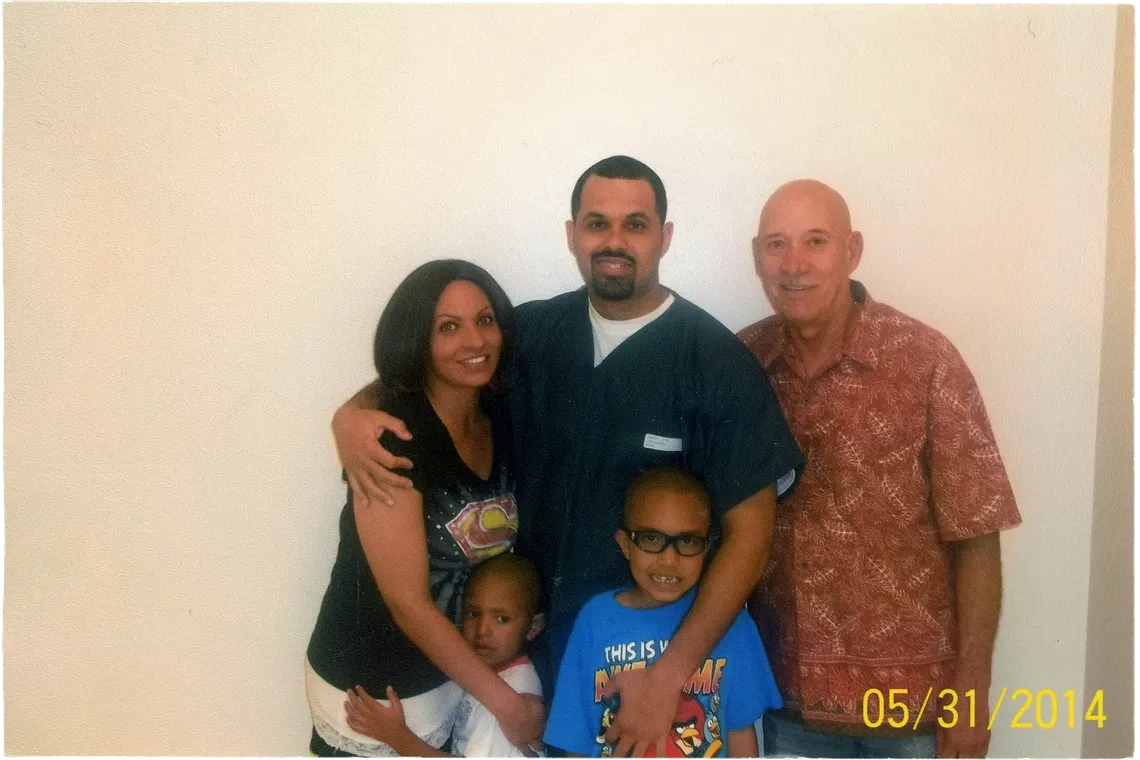

They moved in together. He became a father to her one-year-old son. He found a job, and then a better one, and then a union job, working construction on skyscrapers in the center of Denver. The family went to church. They took older relatives in at their new, bigger house in a nice section of Aurora. There was another child, also a boy, and a wedding timed for when he’d be done with his five years of parole. And, eventually, the demands of everyday life papered over the past. Life became about bills, chores, church, and soccer with the boys. Days and weeks passed with only the smallest reminders of the person he’d once been.

Then on Tuesday, Jan. 7, 2014, he was getting ready for another day in the sky, installing glass windows in buildings high above the city. His cell buzzed. He didn’t recognize the number. The woman on the line said she was from the Denver public defender’s office. She didn’t understand it all herself, not yet. The prosecutor was saying that his release from prison five years and eight months earlier — a lifetime ago, a life he’d managed to mostly will out of his mind — had been a mistake. A clerical error. A judge just signed off on the order. He had to go back.

For the longest time, he had no words. Finally, he managed a question.

Is this even possible?

Officers came to get him that day. They let him hug his young boys one last time, and then cuffed him out of their sight. And at a hastily arranged hearing, it was all confirmed. Rene Lima-Marin’s next chance at freedom would be in 2054, when he would be 75 years old.

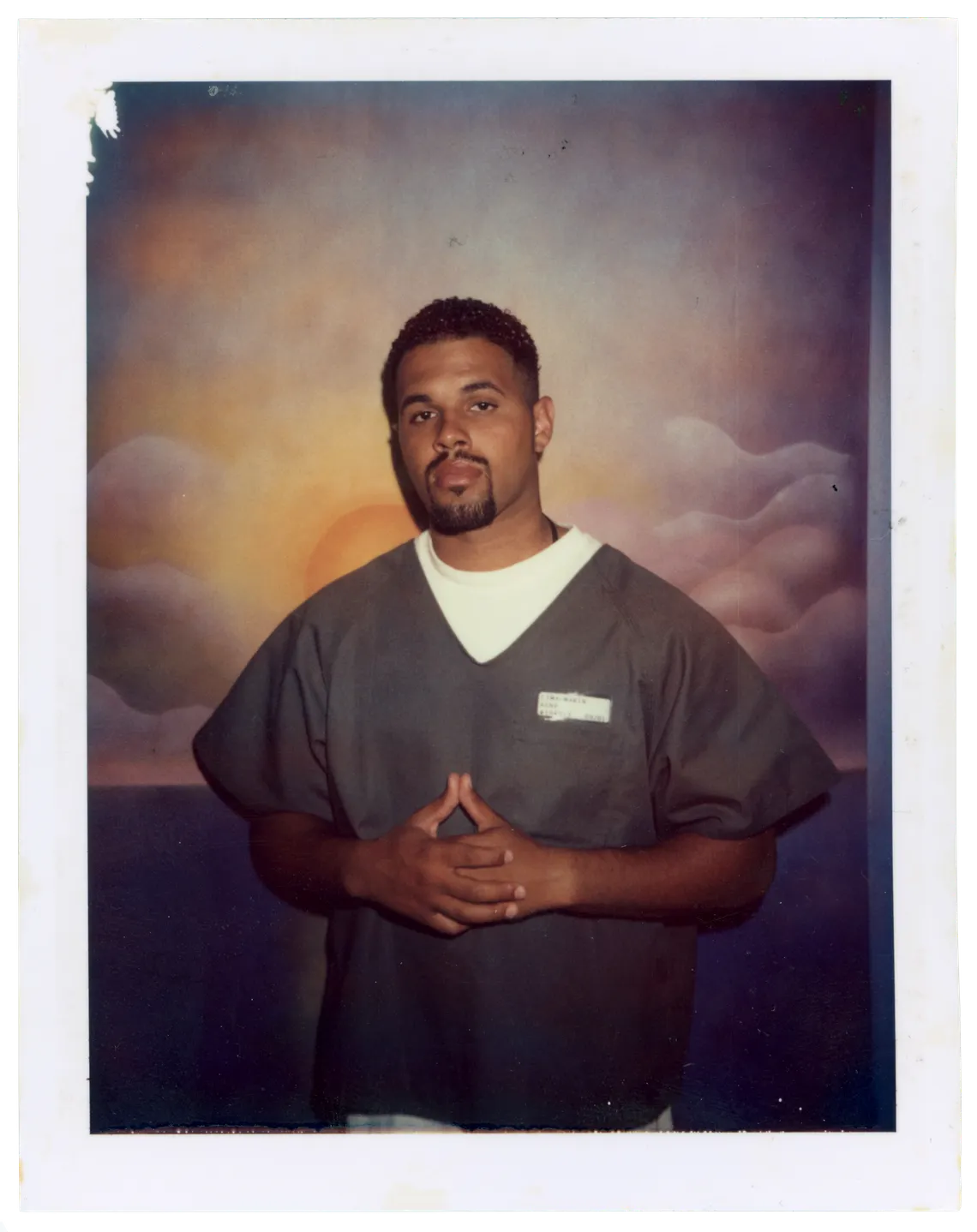

The Kit Carson Correctional Center is a medium-security state prison on an empty expanse of Midwestern plain, about as far from Denver as you can get and still be in the state of Colorado. One of about 700 inmates, Lima-Marin — now 36, with broad shoulders and a head of wiry dark hair, still short — has found a few things to do that will keep him out of trouble: a business class in the mornings, a Bible-study group on Saturdays and Sundays, some chess in the common area when he feels like it. That still leaves too much time to think about what’s happened. It doesn’t help, he says, when practically everyone he sees, inmates and guards alike, seem to acknowledge that he may be one of the only guys who really doesn’t belong there.

In a swivel chair in a small interview room down the hall from his cell, Lima-Marin seems unaccustomed to confinement — still modulating his bodily movements for a life inside concrete, cutting off his arm gestures before they become too expansive. His voice is steady but also guarded, as if he knows if he tries too hard to explain himself he’ll only seem defensive. “You have numerous amounts of time to just reflect and think, ‘Why is this happening?’” he says. The one moment he tears up during my visit is when he talks about his sons — missing Thanksgiving with them, missing Christmas. “I’m constantly replaying that in my head — not being there and experiencing things with them. And watching television doesn’t help me any because everything you watch, it all points to family.” Coming back inside, to him, is most jarring because of how, despite the last five years, it all is so familiar. “Nothing really changes,” he says. What has changed, he says forcefully, is him.

The young man who went in 17 years ago was so different, he says, he even went by a different name. Lima-Marin had dropped the “Lima” and went by Michael then, a more American-sounding name than the one he’d been given in Cuba. His parents had brought him to America when he was two in 1980, during a period when Castro was letting some people leave. His father had been a welder in Cuba; in the U.S., he worked janitorial and carpentry jobs. His mother had been a nurse; she worked at a bank and sold cars. They argued often and eventually divorced. By then, Michael was 16 and had already served one term in a juvenile prison for stealing cars.

Getting the cars was easy: Smash the window, pry out the ignition slot with a hammer and screwdriver, and you’re on the road. He did it with his best friend, Michael Clifton, with whom he’d formed a sort of two-person gang. “We were like brothers,” Lima-Marin says. “We were always together.” Their friends called them the two Michaels. Clifton was almost a full head shorter than Lima-Marin, but just as audacious. “The girls loved them,” says Clifton’s older brother, Derrick. “They were definitely sharp. They definitely fed off each other.” Their thing wasn’t drugs or booze, but money. They both wanted to be players, with the right clothes, the right jewelry, the right car stereos. “It was all about girls and having things and looking nice,” Lima-Marin remembers. “And because we didn’t have the money, we wanted to get and have all these things as quickly as possible.”

Not long after Lima-Marin’s parents had split up, he took over the lease of an apartment his mother was renting, and he and Clifton made it their headquarters. It was during this time that, in 1998, Lima-Marin noticed Jasmine Chambers at the mall. She was 16, two years younger than Rene. She remembers him as a player, not to be tied down; he remembers how innocent she’d seemed. “She wasn’t really impressionable,” he says, meaning it as a compliment. “She was just kind of sweet.”

Lima-Marin and Clifton both got jobs for a short time at a Blockbuster around the corner from the apartment; Clifton even became a manager. But by then, their social schedule came with a big budget. They were regularly throwing parties in their apartment. Friends crashed there all the time. To keep it all going, they needed more money than any day job could provide. Together, they devised a plan.

They knew how their Blockbuster operated — and so, by extension, they knew how all the other Blockbusters in Denver operated, too. They knew that each location had a safe in the back, and that at least one person on duty had the combination. They knew where the surveillance equipment was, and which machine had the tapes. They knew that all employees were instructed to cooperate during a robbery, to ensure everyone’s personal safety. They thought they’d need guns, but not bullets. “We knew exactly how it would pan out, based on what we knew employees were trained to do,” Lima-Marin says. “It felt like a big step, but we worked there. It was a matter of just going in and telling him we wanted the money from the safe.” They thought they were just planning out a heist, nothing more.

The first call to the police came at 9:16 a.m. on Sept. 13, 1998, from a Blockbuster in the center of Aurora. The manager had just arrived for work when two men smashed the window, sent him to open the safe, and left with $6,766. The suspects were wearing bandanas around their faces, one carried a long rifle. There was another witness, a man who saw the men leave in a Honda Civic, and noticed it had an out-of-state plate. Moments later, a driver on I-225 called in a reckless-driving complaint about what seemed like the same car. The caller described Arizona plates.

Later that night, it all happened again, this time at a Hollywood Video around the corner. But with another slight variation from the script. Two clerks were in the store, not just one. Lima-Marin and Clifton brought them both into a back room, forcing one onto the floor and the other to open the safe. “They put a gun to the back of my head and said, ‘This is where you’re going to die,’” one of the employees, Shane Ashurst, later recalled. The men took $3,735.

It took only a few days for police to connect the robberies to Lima-Marin and Clifton. The manager of the Blockbuster where they used to work heard that the police were looking for a Honda Civic with an Arizona plate, and she gave them Lima-Marin’s name. The police got a warrant for his apartment and car and found everything: the rifles, the surveillance tapes, the cash. For Clifton and Lima-Marin, it was over. The evidence was irrefutable.

It was a string of robberies, but of course it wasn’t just that. In the eyes of the law, everything about the two friends’ spree was important. Every step mattered. Every movement within those stores.

Both men received two counts of first-degree burglary and three counts of aggravated robbery, for each of the three employees they made cooperate at the two stores. That surprised Lima-Marin. “They gave me three counts because of the three people,” he says, “but I didn’t rob three people. I robbed two stores.” Then came the kidnapping charges: three counts of second-degree kidnapping, because they’d forced three employees in those two robberies to move from one part of a store to another. Lima-Marin is still outraged by this. They were never going to take anyone. “The point of the robbery was to get people to give you the money,” he says.

Lima-Marin wasn’t just facing more charges than he expected, but the prosecutors were pursuing those charges with surprising zeal. Back in those days, Denver had been rocked by years of alarming homicide rates. Gangs had made inroads into the suburbs, including Montbello, where Lima-Marin’s family had lived in a housing project. The high-water mark for public alarm came during the “summer of violence” in 1993, when a stray bullet from a drive-by shooting killed a five-year-old boy and another killed a 10-month-old child on a visit to the Denver Zoo. No suburb of Denver may have done more to try to curb the influx of gang violence than Arapahoe County, the center of which was the town of Aurora, where Rene-Lima and Clifton lived.

In the mid-’90s, public alarm nationally had reached a near-frenzy over so-called super-predators, juvenile offenders so impulsive that they killed or maimed without giving much thought to the consequences. Demographers and social scientists were predicting greater crime waves to come, citing data suggesting that a small percentage of young criminals were responsible for a huge swath of violent crime. The solution, many prosecutors and police thought, was to lock them away for as long as possible until their wild years were behind them. Colorado’s 18th Judicial District, in Arapahoe County, was proudly out in front of the trend. In 1987, the county had debuted a sentencing protocol called the Chronic Offender Program, or COP, to deal with young kids predisposed to committing violent crimes. The perfect target of COP was someone who seemed, on the surface, to be a lot like Lima-Marin: a violent criminal who was young, and therefore statistically more likely to commit more crimes if allowed back on the streets.

A panel would review each case to decide whether it was right for COP. “We tried to look at the entire situation: the entire crime, the previous crimes, and other circumstances,” says John Hower, the prosecutor who handled all COP cases from 1987 to 1993. “But defense lawyers absolutely hated the program. Defendants in the jail would tell others, ‘Don’t do a burglary in Arapahoe County, because they’ll throw the book at you.’” (In the years that followed, COP fell out of use. “The defendants who created a need for the COP program weren’t around anymore,” says Rich Orman, a senior deputy district attorney who has handled some COP cases and who recently became involved in Lima-Marin’s case.)

Lima-Marin says he had been ready to plea out, but when the COP prosecutor at the time, Frank Moschetti, came with an offer of 75 years, Lima-Marin knew he couldn’t accept that deal. Under pre-COP sentencing policies, the plea offer might have been based on concurrent, not consecutive, sentencing, drastically reducing the time he’d have to spend behind bars. Lima-Marin’s only alternative was to roll the dice at trial. Maybe he’d get lucky and the judge would rule the evidence inadmissible. “They left me with no other choice but to try to figure out a way to win, if you will,” he says. “Even though I did do it.”

On Jan. 31, 2000, a jury found both Lima-Marin and Clifton guilty on all eight counts. The sentences were to be served consecutively, for a total of 98 years. Offered the chance to say something before the judge and jury, Lima-Marin was too stunned to speak. Judge John Leopold seemed to sympathize: “I am not comfortable, frankly, with the way the case is charged,” he said as the two men stood before him. “But that is a district attorney executive-branch decision that I find I have no control over.”

So how does a sentence like this vanish? How does 98 years become 10? It didn’t make sense to Lima-Marin, and yet going against it made even less.

He remembers first learning about the possibility of life after prison shortly after arriving at the medium-security Crowley County Correctional Facility, when he received a visit from a public defender assigned to handle his appeal. “I had no clue and no idea of how none of this worked,” Lima-Marin says. As he recalls, his lawyer surprised him by telling him that she didn’t think he ought to appeal at all. The best possible scenario had unfolded, he remembers her saying: “You no longer have 98 years. What you have is 16 years.”

When he said he didn’t understand, the lawyer offered no explanation. He says she never even mentioned a clerical error. From what he could gather, she’d looked at his case file for the first time before meeting him, and when she read it, she saw that his release date was consistent with a 16-year sentence, as if his sentences were running concurrently. Since this matched the most favorable outcome he could expect from an appeal, he remembers her saying that it made no sense even to bother filing one. She handed him a sheet of paper, he signed it, and he never saw her again.

Back in his cell, Lima-Marin wondered how this was possible. Other inmates told him that if he wanted to make sure his lawyer was right, he should ask to see what everyone called his “green sheet,” the official Department of Corrections record of his sentence and parole eligibility. The green sheet was gospel, he was told; whatever was on the green sheet, the DOC would follow. Sure enough, his green sheet confirmed what his lawyer had said: 16 years.

Lima-Marin felt a rush of relief. “I felt like, I still have a chance here. To live life,” he says. His time felt provisional now — his early release was his to screw up. He got into a few fights early on, but they were over too quickly for anyone to notice. Then, about a year and a half into his time at Crowley, he met another inmate, a tall, imposing former gang member who had undergone a transformation. “He’d been an OG, and everyone knew him, but he was completely for God now,” Lima-Marin says. “I wanted to find out why.” Through his new friend, he joined a small prayer group and spent every available moment with them. They offered him independent reinforcement — it could be done; a person could change. He stopped going by “Michael” to underscore the transformation. He was Rene now.

There may have been no more meaningful measure of how much he’d changed than the new view he took of his best friend. Michael Clifton had been sent to a harsher prison, Limon Correctional Facility, which also houses maximum-security inmates. Lima-Marin remembers writing to his friend about his shorter sentence when he first found out, and that Clifton replied with congratulations. “He was like, ‘Man, that’s good’ and all that.” But as he kept reading Clifton’s letters, he couldn’t help thinking they were on different paths. In time, the letters felt like piercing reminders of the person he no longer wanted to be.

“Everything that he wrote me about were things I didn’t want to hear about and I didn’t want to talk about,” he says. “‘I’m doing this over here and gambling over there.’ So I mentioned that to him — not in a way of forcing it — saying, ‘Listen, brother, I’m different, and I’m trying to abide by what I’m learning.’”

When Clifton “kind of blew it off,” Lima-Marin says, he stopped writing back. “I got to the point of this being a lifestyle for me — not a game, not something I do just to be doing it or on specific days. He wasn’t understanding that.”

Lima-Marin’s behavior record at Crowley was clean. In his time there, he’d evidently been a model inmate — an embodiment, some say a rare one, of the system’s ability to rehabilitate career criminals. He was granted parole in April 2008, six years before the end of his 16-year sentence. Just a few days after arriving at his father’s place in Aurora, he sent a MySpace message to Jasmine. They moved in together almost immediately.

He was 29. His entire adult life up to that point had been spent in prison; now he had no money, no job, and no professional qualifications. Jasmine supported him while he got back on his feet. He sold coupon books door-to-door, then worked in a phone bank selling DISH Network subscriptions, and then became the phone bank’s supervisor. Even so, he wasn’t happy. He was starting to feel the same impatience he’d had as a teenager. “I wanted to have more,” he says. “It was somewhat the attitude I had before, but twisted. It was I’m not satisfied with what I have, and I’m going to get it the right way.”

It had never occurred to him that changing might be harder on the outside than it had been in prison. It was easy to replace old worries with new ones. There was the lack of simplicity and structure to life outside. “There are a lot fewer temptations in prison,” he says. “You study every day. You don’t have to put food on the table, everything is provided for you.” In the real world, he ministered to young people at group homes, and he recorded some rap gospel music with his friends (I’ve been selected and tested to overcome this oppression / Of sin and bondage that’s trying to hold me down but I’m pressing / It’s God's protection that brought me through these times of depression / ’Cause through the spirit they can hear it ’cause it won’t be neglected). But he had distractions, responsibilities. Weekly trips to church became erratic. “It was me just being me, I guess.”

But soon, his life gained a new shape. He married Jasmine. He worked to become vested in his union. “I remember talking to a friend. I said, ‘Look at where I am. I was in prison for the rest of my life. Now I have two boys, we both have nice jobs, we both have cars.’ I was kind of proud of what I had accomplished.”

There was only one outstanding reminder of the past, one he did his best to ignore. One day, Lima-Marin ran into Clifton’s brother, Derrick, at the Aurora mall. “I almost wanted to hide,” he says. “I thought, ‘Should I turn, do I not want him to see me?’ But I didn’t. I just walked up to him. He never mentioned his brother.”

Derrick Clifton remembers this, too. “It was like I’d seen a ghost. ‘No way, this is Michael Marin standing right in front of me?’ And then all kinds of stuff starts to go through your head. Like ‘How is he out?’ And ‘This don’t make sense.’ And ‘Where is my brother?’ And ‘What’s going on?’”

“I’m in a tight situation,” Michael Clifton says over the phone one evening from Sterling Correctional Facility in central Colorado. He still calls his onetime friend by his old name, Michael Marin. “We did everything together. We called each other brothers,” he says. “We used to like to dress where we’d coordinate our clothes. Our thing was females. We’d always just hang out and shop, whether it was legal or illegal, for our clothes and jewelry.”

Their lives, of course, had diverged behind bars. Where Lima-Marin had a clean record, Clifton stabbed another inmate, and was punished for it with time at the Colorado State Penitentiary, a Level V maximum-security prison. And while Lima-Marin found religion, Clifton joined the Bloods — as sort of an adjunct, non-active member, he insists. Even now, Clifton is housed at Sterling, “the deadliest prison in Colorado,” he notes, with six reported homicides since 2010.

Clifton has been looking forward to speaking up about his old friend’s case, because from the first time he heard about the change in Lima-Marin’s sentence, he’d thought Lima-Marin’s good news might translate into his own. “We were both given excessive sentences,” he says.

He says he’d known about Lima-Marin’s suddenly shorter sentence for years and never told anyone about it. But he has a different recollection of when Lima-Marin learned the news. According to Clifton, it happened just after their conviction, at the Denver Reception & Diagnostic Center. “When I came back from seeing my case manager, I got to talk to him [in the hallway] before we went back to our pods,” he says. “I was shocked. But he showed me the actual paper, and his PED” — parole eligibility date — “was, I think, 2014. My PED at that time was 2046.”

He offered right away not to mention the mistake before Lima-Marin was safely out and through his parole. This was no small thing: It meant that Clifton couldn’t note the discrepancy in his appeal attempt. “I wasn’t going to bring it up,” he says.

According to Clifton, Lima-Marin didn’t seem to care about anything Clifton was saying about covering for him. He was more focused on the deeper meaning of what had happened. “He said, ‘Man, I’m going to change my life. I’m going to do a complete change, man. I’m gonna give my life to God.’” Only now, perhaps, does Clifton understand how serious Lima-Marin must have been about that. “When you look at that error or mistake,” he says, “you do think that you’re getting a second chance.”

Clifton remembers how their friendship faded much the same way that Lima-Marin does: Lima-Marin’s objections to his coarse language and subject matter of his letters; their correspondence falling off gradually. There’s only one bitter note in Clifton’s version, a passive-aggressive moment after they’d broken off contact, when he was in 23-hour lockdown, that he sent Lima-Marin a letter, but left it completely blank.

Rich Orman, in the Arapahoe County prosecutor’s office, received an email at 7:44 a.m. on Jan. 7, 2014, from a magistrate judge who years earlier had been the prosecutor who had secured the convictions against Lima-Marin and Clifton. The subject line was “A question out of the blue.”

Rich,

I was just checking the DOC inmate website, and there is a person I prosecuted under the COP program who is not there. His co-defendant, Michael Clifton, is there (with an initial parole eligibility date some 30 years away)…. I am hoping somehow I just may have missed something, but I fear that somehow he might have been mistakenly released early or something.

Would you mind checking into the situation?

Thanks,

Frank Moschetti

Orman called the DOC at once. He learned not only that Lima-Marin was free, but that he’d been out more than five years, completing his parole. He checked the state court’s computer system and noticed a strange phrase tacked on to each of Lima-Marin’s eight convictions: “No Consecutive/Concurrent Sentences.” Orman wondered if someone else might have been as confused by that phrase as he was, and decided that his sentences were concurrent.

Orman notified the judge of the error in a memo by 12:30 p.m., and had the judge’s order in hand two hours later. Lima-Marin was arrested that night, and the hearing that sent him back to jail took place the following day. “People talk about inefficiency in government?” Orman says, smiling. “This was very quick.”

One reason for the speed may have been that officials were still reeling from another case of an inmate’s accidental release. In January 2013, a 28-year-old prisoner from Colorado named Evan Ebel had been released four years early. A clerk had mistakenly written in his file that the sentence was to be served concurrently. Two months later, Ebel killed two men, including the Colorado prisons chief, Tom Clements. The case had sparked an audit of other cases; even so, Lima-Marin’s case reportedly did not come up in that audit, escaping scrutiny until Moschetti noticed it several months later.

The Ebel and Lima-Marin cases are not the only ones with clerical glitches. In April 2014, a California murder suspect named Johnny Mata was released when the court clerk failed to enter an order to keep him in custody; he fled to Mexico, where he was captured. In a string of Nebraska cases last year, at least 200 prisoners were released as a result of a flawed computer formula used to calculate sentences. The Denver Sheriff Department reported five erroneous releases from its Downtown Detention Center during a 10-month span in 2014; at least one of those was blamed on an inaccurate court order. And in another case, a Missouri man named Cornealious Anderson was sentenced to 13 years for armed robbery in 2000 but never received information on when and where to report to prison. He started a business, got married, had kids, and volunteered at his church before the error was caught on July 25, 2013, just as his original sentence was supposed to end. Anderson was sent to prison to serve out his sentence but was released on May 5, 2014, the judge calling him a changed man.

Last March, Lima-Marin’s new public defender, Marnie Adams, filed a motion with the court arguing that Lima-Marin no longer deserved or needed prison, and that to send him back amounted to cruel and unusual punishment — and that he had “a legitimate expectation of the finality” of his prison sentence when they let him out in 2008. His life outside prison proved he’d changed: “Now, Mr. Lima-Marin is a committed family man who inspires others with his love and dedication to his family.”

In a lengthy reply on behalf of the state, Rich Orman described Lima-Marin’s five years and eight months of accidental freedom as a great stroke of luck: How many other inmates would have jumped at the chance for a half-decade furlough? The fact that Lima-Marin lived like a model citizen for five years, Orman argued, should have no bearing. “Plainly said,” Orman wrote in his reply, “the Defendant had no business getting married and starting a family.”

On April 21, Judge William Sylvester sided with Orman, ruling against Lima-Marin’s motion to be released. The judge cited a ruling from White v. Pearlman, a 1930 case in which a clerical error released an inmate two years early, that there could be “no doubt of the power of the government to recommit a prisoner who is released or discharged by mistake.” He went a step further to say that Lima-Marin “could not have had a legitimate expectation of finality in his original sentence when he was mistakenly released early, based on a clerical error.” Lima-Marin hired an appeals lawyer, Patrick Megaro, who had represented Cornealious Anderson in Missouri. To Megaro, the main question of Lima-Marin’s case is not whether he knew about the clerical error and should have brought it to the state’s attention; it’s whether he should be punished for the state’s mistake at all. “To conclude [Lima-Marin] should have insisted that he was being wrongfully released from prison ignores reality,” Megaro argued in an August motion. “No rational individual would question the motives or correctness of his jailers and insist that they remain in prison for the rest of their life.” Megaro has asked to appear before the court to contest the matter in oral arguments. A hearing date has yet to be set.

Lima-Marin understands the strangeness of his life — that the same clerical error that brought him out of jail may have saved him. Without that error, he thinks, his time in prison may have been like Michael Clifton’s, turbulent and violent. Without that error, he might never have built a family at all. Without that error, he sometimes wonders, who would he be? “Some people might think this is extreme,” he says. “But I feel to a certain degree, that some of this is about to me.”

His family is caught up in this now. Back in Aurora, Jasmine and a group of clergymen are lobbying the governor to grant her husband clemency. They have not heard anything yet. She is raising an eight-year-old and a four-year-old by herself. She tells them that she doesn’t know when their father will come home. The younger boy, Josiah, or Jo-Jo, has been acting out, doing a lot of baby talk. Jasmine and the boys can afford to drive out to see Lima-Marin once a month. He and Jasmine talk on the phone every night. They weren’t going to church so often before he went back to prison. But she’s been going weekly ever since, with the kids. The pastor has been telling Jasmine that what is happening to her and Lima-Marin is a test. She is inclined to agree. So is he.

Our visit is coming to an end. After we talk, Lima-Marin will return to his cell and resume his old prison life, for how long he doesn’t know. He seems restless now, speaking more urgently, trying harder to get across what he thinks is really happening to him and what should happen. On one level, he believes he is reformed and that he’s proven he no longer poses a risk to society — that he’s a new man serving an old sentence. “What’s happened to me, it’s obvious to me, is wrong,” he says. He often says he’s being punished for the same crime twice. That’s why he thinks he’s being subjected to a second glitch.

Lima-Marin’s life, after all, has comprised a series of reversals, each of them drastic: from a life sentence to freedom; from ex-convict to faithful father; from selfishness to religious fervor. And now, every inch of progress has been ripped away. There has to be a reason.

He searches for it in memories: skipping church every now and then to coach soccer. Ministering with his music, but not face to face. “I’d come home and I’m tired. And then you have the bills. There’s so much going on. I’m not putting forth all of the effort that I’m supposed to be into the word, into study, into prayer. I pushed the Lord to the side, and it became about life.”

He looks up, pausing, worried he’s said too much, struggling to find the right words. And then he does. “Jonah ran from what God wanted him to do,” he says. “So he had to be placed in a position to be able to hear from God.”