You might guess that police fire their weapons most often in neighborhoods with the highest levels of crime, poverty and racial segregation. But preliminary research from a team of St. Louis criminologists complicates that notion, and suggests some lessons for reducing police shootings.

David Klinger, Richard Rosenfeld, Daniel Isom and Michael Deckard of the University of Missouri studied 230 incidents in which St. Louis police officers discharged their guns, between 2003 and 2012. Past research on police shootings has been limited by the federal government’s severe undercounting of such incidents, and has tended to look primarily at shootings that result in a civilian’s death. The new paper, however, relies on all of the St. Louis Police Department’s internal incident reports on shootings, and includes events in which no one was killed or even hit by the resulting bullets. This methodology is important to understanding police violence, because “when officers shoot and miss or injure, it’s really a potential shoot and kill,” according to political scientist Charles Epp of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who was not involved in the St. Louis study.

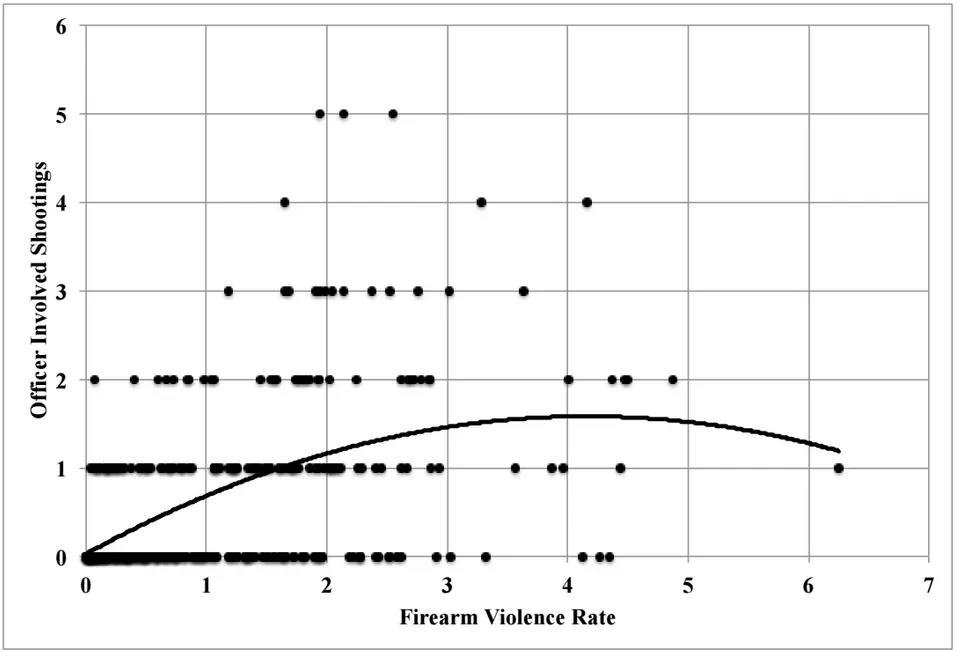

Using census data, the St. Louis researchers then examined the income level, racial composition and rate of firearm crime — homicides, assaults and robberies involving a gun — in the neighborhoods where shootings occurred. Of the city’s 355 census tracts, 59 percent experienced no police shootings at all. But within the five percent of neighborhoods with three or more shootings, a surprising pattern emerged: Neighborhoods with five shootings had higher incomes, a smaller black population and lower levels of gun crime than neighborhoods with three or four shootings.

The research team offered a couple of explanations for why police shootings might be clustered in relatively privileged areas. First, 35 of the 230 St. Louis shootings took place when officers were off-duty, and officers tend to live in whiter, more affluent areas with lower crime rates.

When the researchers removed the off-duty shootings from the data set, the results that emerged were more relevant to the national debate over the deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Tamir Rice in Cleveland, and, most recently, Tony Robinson in Madison, Wis. — all of whom were shot by on-duty officers. The rate of firearm crime in a neighborhood then became a better predictor than race or income of how many times police shot their guns during their work shifts.

As you might expect, neighborhoods with three police shootings had higher rates of gun crime than neighborhoods with fewer shootings. But the researchers noticed a “turning point” in the data that created a U-shaped curve: Neighborhoods with five police shootings were relatively safe, with less firearm crime than neighborhoods where the police fired their weapons three or four times.

The research has not yet been peer reviewed or published, and because its methodology — tracking gun discharges by census tract — is new, it is unclear whether the pattern would hold true in other cities. But Klinger, Rosenfeld, Isom and Decker propose that “mindfulness” is the key factor explaining the clusters of shootings in less crime-prone neighborhoods. Just as car drivers are less likely to hit pedestrians and cyclists in neighborhoods with a greater number of people on foot and bike, they write, police officers in areas with more firearm crime are habituated to the risk of violence, and so are more prepared to de-escalate potentially deadly confrontations without discharging their weapons.

“When officers are alert to the prospect that this could be a dangerous situation, they tend to use more rigorous tactics,” said Klinger, a sociologist and former police officer. “They tend to be more on their guard. They create space between themselves and a suspect and coordinate more completely with other officers on the scene.”

Klinger has written and spoken about his own experience as a Los Angeles police officer when, on July 25, 1981, he shot and killed a 26-year-old man who had been in the process of stabbing Klinger’s partner officer. A year later, Klinger responded to a call about a man wielding a gun. Shielding themselves behind cars and buildings, he and a team of officers were able to disarm the suspect by shouting commands.

The new study suggests that training to avoid conflict, sometimes called tactical retreat, tactical withdrawal, or tactical restraint, is key for all officers, even those who don’t work in high-crime areas. Yet the idea that officers should back away from suspects has been controversial within the policing profession. Gabe Crocker, president of the St. Louis police union, called tactical retreat “cowardice retreat” and “shameful.”

Klinger prefers the terms “repositioning” or “reconfiguration” to describe police creating distance between themselves and violent suspects. “If what you do is tell police officers to retreat, they will think, Well, if somebody’s life is in jeopardy, that’s the wrong thing to do. We need terminology and training that explicitly outlines the situations in which it is appropriate to reposition. If repositioning creates more danger” — such as when Klinger’s partner was being stabbed — “then you don’t do it. If, however, it is safe to do so, repositioning is appropriate.”

The study did not include data from Ferguson, where Michael Brown was killed, because the town lies outside St. Louis city limits and has its own police department. Yet Ferguson’s demographics — less black, less poor and less violent than the typical St. Louis urban neighborhood — suggest police there might have lacked experience in defusing potentially violent encounters.

“Michael Brown had reached into [officer Darren Wilson’s] car,” said study coauthor Richard Rosenfeld, chairman of the National Academy of Sciences roundtable on crime trends. “The officer at that point could have driven his car 10 yards ahead. At most, Michael Brown would have fallen to the pavement, but he would not have been killed. Wilson had the option to use deadly force to stop an imminent threat. But that wasn’t the officer’s only option, in my view.”

Of course, training by itself may not be enough. For one thing, race matters. In a city that is about 48 percent black, 93 percent of the suspects shot at by St. Louis police were black, and 96 percent were male. White and black officers were about equally likely to discharge their guns. Research on implicit bias shows people of color can have racist biases, just as women can have sexist ones. And social scientists have estimated that attitudes, including racial bias, predict about 10 percent of an individual’s behavior.

Tracey Meares of Yale Law School, a member of President Obama’s 21st Century Commission on Policing, pointed out that the Justice Department’s report on policing in Ferguson showed that the police’s treatment of black citizens was driven by yet another factor: the desire to collect court fees.

“This is about the political economy of a criminal justice system that is shaped by the relationship between police arrests and court fines, and the distorting impact of that,” Meares said. “There is no training [in avoiding force] because they have every incentive not to train.”

A previous version of this story inaccurately stated which year former Los Angeles police officer David Klinger shot a man. It also misstated the location of a call he responded to the following year.