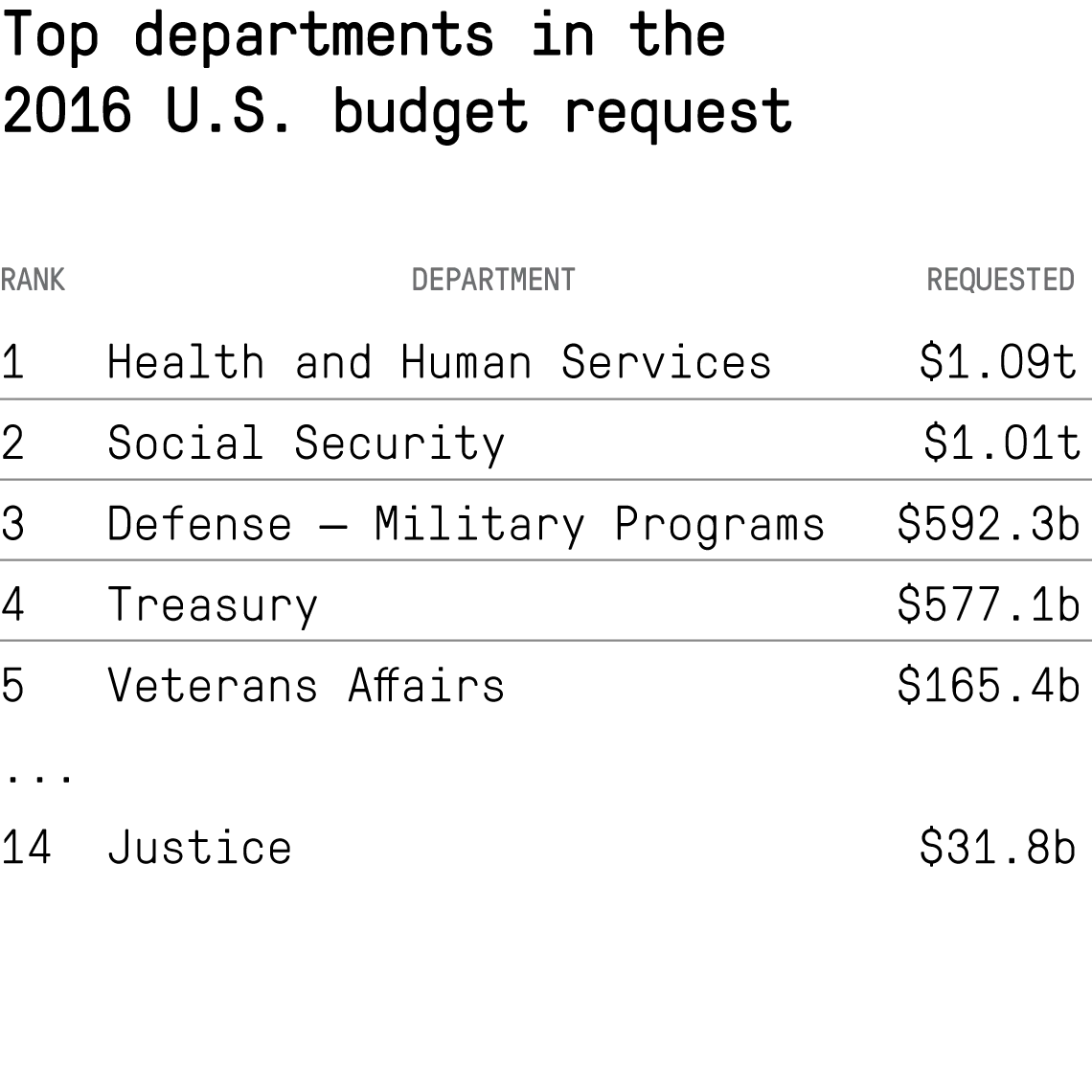

When the White House unveiled its proposed budget for 2016 last week (also available on CD-ROM), it came with a trove of historical data, including spreadsheets of the federal budget, income, and expenses from the past six decades.

The Department of Justice, whose mission is to “enforce the law and defend the interests of the United States,” is a surprisingly small line item in the context of the entire federal budget. Over the past 50 years, the DOJ has topped 1 percent of the total budget only three times. And next year’s request follows course, with the White House asking for nearly $31.8 billion1 for the Justice department — out of a total budget of more than $4 trillion.

To better understand how the DOJ’s spending over the last half-century reflects the country's shifting criminal justice priorities, The Marshall Project examined its four largest bureaus — the FBI, the U.S. Attorneys and Marshals, the Bureau of Prisons, and the Office of Justice Programs. Combined, they account for more than 80 percent of the money the department spent between 1962 and 2014. We compared each bureau’s annual spending – adjusted for inflation – to its percentage of the DOJ’s overall expenditures.

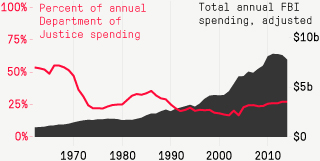

1. The FBI - $178.3 billion spent from 1962-2014

Since 1962, the FBI has been the top spender in the DOJ, and during the 1960s, it accounted for more than half of the department’s expenses. But in the early 1970s, even as spending grew, two tides began to erode the FBI’s share, halving it within a few short years.

First, the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA) – created by the 1968 Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act to support local police agencies and disseminate best crime fighting practices – emerged as a major priority for the department, diverting funds away from the FBI.

More significantly, however, was the waning influence of its founder and patriarch, J. Edgar Hoover. Before his death in 1972, his beloved bureau fell out of favor after Hoover clashed with President Richard Nixon over surveillance policies. So as the Justice department grew, the FBI’s spending remained nearly flat through the decade.

The bureau found more firm footing during the Reagan years, and by the 1990s, was wrestling with the Drug Enforcement Administration over who should take the lead in the nation’s war on drugs. After the bombing of the Oklahoma City federal building and the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, the FBI took the lead on domestic counterterrorism, and its expenses have grown in kind.

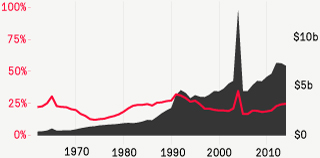

2. The U.S. Attorneys and the Marshals Service - $162.2 billion spent

The biggest chunk of the money in this bureau goes to the 93 U.S. Attorneys and their staffs, who are responsible for prosecuting criminal and civil cases for the federal government.

The next largest expense is the Marshals Service, in many ways the backbone of the federal court system. Its agents guard courthouses, and they protect judges, prosecutors, and justice department leaders. They transport prisoners between courts and facilities across the country, and they hunt down fugitives. They also oversee federal prisoner detention, the witness protection program, and the asset forfeiture program.

While the Attorneys’ and Marshals’ share has remained relatively stable over the past couple decades – between 16 percent and 28 percent – spending started increasing as the entire DOJ budget grew during the late-1980s and through the 1990s.

In 2004, there was one brief spike when expenses for the bureau more than doubled in a single year: The Sept. 11 Victims Compensation Fund disbursed $6.3 billion.

3. The Bureau of Prisons - $151.6 billion spent

In the 1960s, the federal prison system was the third-largest bureau and accounted for one-fifth of the DOJ’s spending. By the next decade, the department was on a spending spree, and the competition for funds increased as more bureaus were established.

As the federal prison population started to grow (from 1980-2012, it rose more than 800 percent), the Bureau of Prisons’ share of the DOJ’s expenses began to steadily climb. Mandatory minimum sentences and increased drug enforcement were primarily responsible for the prison boom, and spending skyrocketed, according to former deputy attorney general Philip Heymann. The expenses of the Bureau of Prisons went from an all-time low of 10 percent in the mid-1970s, to its peak — 27 percent — in the mid-1990s.

After a small dip, the Bureau of Prisons’ expenses have held roughly steady for the last decade, at around 22 percent.

“The Bureau of Prisons is viewed within the Department of Justice as a must-pay bill,” said David Maurer, the director of Homeland Security and Justice issues at the Government Accountability Office. “They have to house and feed and provide programming and medical services for inmates. There is also no option to suddenly lay off half of the correctional officers."

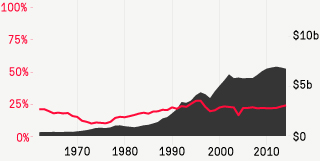

4. The Office of Justice Programs - $130.1 billion spent

The Office of Justice Programs and its components like the National Institute of Justice and the Bureau of Justice Statistics are charged with studying crime and policing, and sharing innovative approaches (and money) with local police agencies.

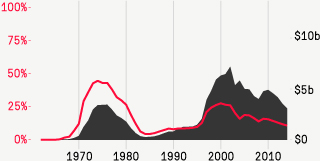

A graph of the spending by the office, and its predecessor the LEAA, illustrates a long-running debate about what role the federal government should take in policing. Flush in the 1970s, there was government money to spend on studies, advice, and equipment. At its zenith, in 1974, the LEAA made up nearly 45 percent of the DOJ’s spending. But as the country teetered between recessions, the LEAA became a popular target for cost-cutters, who deemed it overly bureaucratic and ineffective at providing solutions to the crime problem. It was abolished in 1982, when Congress failed to appropriate money for its budget.

A few years later, it was resurrected as the Office of Justice Programs and experienced a renaissance during the Clinton administration. Jeremy Travis, the former director of the National Institute of Justice, described the years after the 1994 Crime Bill as a golden era for the Office of Justice Programs: "It reflects a shifting national consensus on whether the federal government should have a role in crime, which is almost the quintessential local condition. What should the role be? Should it be research or money for technical assistance and program development and that sort of thing?"

At the peak of its second wave in 2000, the office’s expenditures constituted about 28 percent of the DOJ. Since then, its spending has fallen to about 10 percent of the department, considerably less than the top three, but far more than most other parts of the agency.