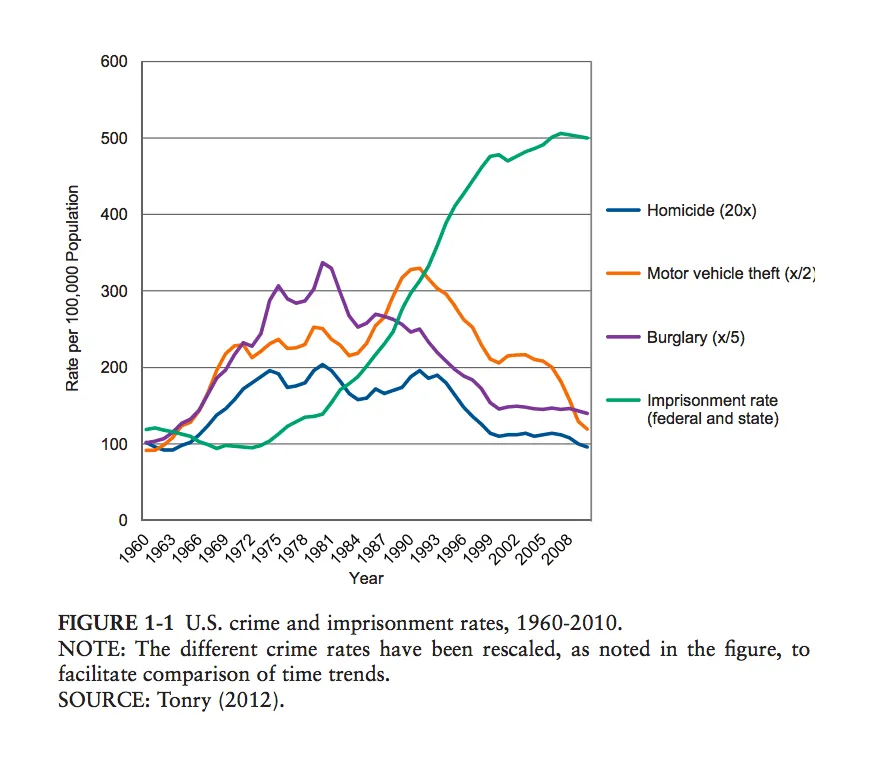

In his State of the Union address Tuesday, President Obama celebrated the fact “that for the first time in 40 years, the crime rate and the incarceration rate have come down together.” The American incarceration rate, as it is widely known, more than quadrupled from 1970 to 2010. Since the early 1990s, crime has dropped steadily, yet the incarceration rate only began to decrease in 2010. So the president’s comment raises some interesting questions: Why did it take so long for the crime and prison rates to drop at the same time? And why has the overincarceration trend begun — slowly — to reverse?

Crime surged during an era of social upheaval.

According to a report on the history and impact of mass incarceration, published last April by the National Research Council of the National Academy of Sciences, the violent crime rate nearly doubled between 1964 and 1974. Historians suggest a number of reasons why: There was a population bubble of young men coming of age, which tends to produce higher crime rates. Anti-war protesters were demonstrating in the streets, and police were cracking down. The Great Migration brought southern blacks into northern and western cities just as the manufacturing economy began to falter, with well-paid factory jobs harder to come by. Some young men turned toward the criminal underground, especially the drug market, for work.

In the South, whites responded violently to the legal dismantling of Jim Crow. In cities like Los Angeles and Newark, riots followed reports of white police brutality. On television, Americans saw harrowing images of urban neighborhoods burning and teenagers sacking storefronts.

Fear of crime had surged before, at the turn of the twentieth century, as poorly educated immigrants flooded into American cities from eastern and southern Europe. But during the Progressive Era, newspapers and magazines took hold of a “root cases” narrative, suggesting that poor white immigrants broke the law largely because of a lack of decent housing, education, employment, and health care.

The crime wave of the 1960s, captured in Technicolor, produced an entirely different public conversation. The increase in crime and public disorder took place amid racial upheaval and coincided with the (often expensive) implementation of a number of liberal, Great Society social programs, including school desegregation, Medicaid, and Head Start. During the same decade, Earl Warren’s Supreme Court issued a number of rulings that critics portrayed as too easy on defendants, such as the 1966 Miranda decision requiring police to inform suspects of their right to remain silent.

The long-term demographic trends that created the crime wave predated both the Warren Court and President Johnson’s Great Society. Yet the concurrence of high crime and liberal policymaking created the appearance that the “root causes” approach to fighting lawlessness had failed. Both Democrats and Republicans turned toward policing as a remedy.

The federal government got more involved in local law enforcement.

In a new book, “The First Civil Right,” Princeton political scientist Naomi Murakawa points out that liberals first argued for nationalizing police tactics. In 1947, in response to lynchings and reports of white police brutality, President Harry Truman’s Committee on Civil Rights called for federal funding to help “professionalize” local police forces. At the time, the idea was to provide anti-discrimination training “so as to indoctrinate officers with an awareness of civil rights problems.”

During the 1960s crime wave, support for an increased role for Washington in local policing reemerged. In 1965 and 1968, Congress passed crime bills that provided funding for expanding prison capacity, hiring more police officers, and purchasing new policing equipment. Federal dollars flowed into municipalities enamored not with Harry Truman’s vision of civil rights policing, but with an innovation called SWAT teams, whose militaristic weapons and tactics were borrowed from guerilla warfare tactics in Vietnam.

A War on Drugs was launched.

President Johnson created the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs in 1968, an early parry in the drug war. But as Radley Balko writes in “Rise of the Warrior Cop,” Richard Nixon positioned drug use, politically, as “the common denominator” that explained lawlessness among hippies, inner-city blacks, and anti-war protestors alike. In 1971, Nixon declared drugs “public enemy number one” and asked Congress for new funding to wage “an all-out offensive.” The political logic linking drug use (as opposed to drug sales) directly to urban violence was faulty. Research already existed showing drug users were less likely than non-drug users to be arrested for murder or assault.

Nixon established the Drug Enforcement Agency in 1973 with the goal of fully eradicating illegal drugs, largely through aggressive policing. History proved that federal attempts to prohibit substances led to increased violence. Crime had spiked during Prohibition, when organized gangs fought for control of the underground alcohol supply chain, with local police and the FBI in hot pursuit. In the 1970s, too, as police scrutinized the drug market more closely than ever before — through investigations, street arrests, and SWAT raids of private homes — unprecedented numbers of people entered the criminal justice system for the possession and sale of illegal drugs, often in small quantities.

Politicians changed sentencing laws.

None of this would have quadrupled the incarceration rate if sentencing laws had not changed. New York’s Rockefeller Drug Laws, passed in 1973, became a national model. They established a mandatory minimum sentence of 15 years in prison for selling two ounces, or possessing four ounces, of marijuana, cocaine, heroin, or morphine.

Between 1975 and 1995, all 50 states and the federal government enacted sentencing rules requiring judges to impose long prison terms for drug crimes. California’s widely imitated “three-strikes” law mandated a sentence of 25 years to life for those convicted of three felonies, even if all three were for possession of small amounts of drugs. In response to federal incentives, more than half the states eradicated or limited parole, under which inmates can be released early for good behavior. As a result, those serving time for nonviolent drug offenses often had longer sentences than people convicted of robbery, murder, or rape.

Long prison terms were supposed to deter crime by incapacitating career criminals. But the National Research Council came to the clear conclusion that longer sentences had little effect on the crime rate. Why? Because criminals — especially drug criminals — age out of their law-breaking by middle age, even when they are outside prison. “Having a person serve a 15-year sentence instead of 10 years is going to have very little incapacitation or deterrent effect,” says Jeremy Travis, chair of the National Research Council committee on mass incarceration and president of John Jay College. “The aging process is well documented.”

Since the recession hit in 2008, the Rockefeller laws have been partially dismantled, California has reformed “three strikes,”and the federal government has decreased the sentencing disparity between crack and cocaine offenses. A series of court cases have made the tough-on-crime federal sentencing guidelines of the 1980s and 1990s optional for judges. Yet the drop in the incarceration rate that Obama mentioned in the State of the Union represents only about a 1 percent change. In fact, although the raw number of federal and state prisoners declined from 2010 to 2012, it rose again in 2013. Most of the laws and regulations that created mass incarceration remain on the books.

“We need to recognize that it took four decades to build up a prison population to four times the previous rate,” Travis says. “And it will likely take decades to bring about significant reductions.”